History's Most Inspiring Women You've Never Heard Of

The way our society teaches and learns history has shaped the way the world is viewed today. But history books have often overlooked the stories of some of history's most important and interesting figures. Women, for instance, get left out of many accounts. While we've heard the stories of many men, women who accomplished similar or even more significant feats often go unmentioned. And we want to celebrate those lesser-known ladies.

Choosing the women with the most inspiring backstories is impossible. Not only are there so many inspiring women to choose from, but some of the women who helped shape history will likely remain unknown. Records and history books from years past were often written by men, or at least written during times when men enjoyed nearly exclusive access to status. As a result, many women never even made it into the records at all — or if they did, their lives were misrepresented. But from what has been recorded of the important women in history, there are lots of things to learn. Here are some stories of women from history who will undoubtedly inspire you.

Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace was the only legitimate child of the famous poet, Lord Byron. But that's not why she is famous. Lovelace is widely regarded as the world's first computer programmer. She published the first ever computer algorithm and worked closely with mathematician Charles Babbage as he developed an early mechanical general-purpose computer called the Analytical Engine. Who knew that the male-dominated field of computer programming was actually pioneered by a woman?

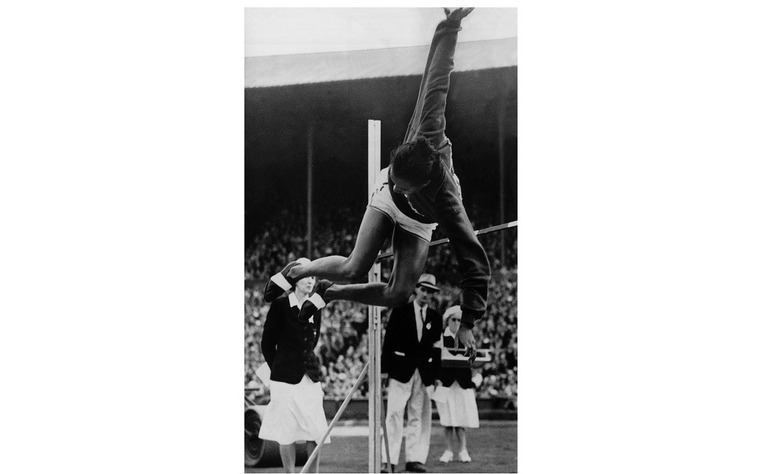

Alice Coachman

Alice Coachman was the first black woman to win an Olympic gold medal; in 1948, she won the United States the gold for the high jump. Growing up in Georgia, Coachman was banned from training on many athletic fields because she was black, so Coachman got creative. She made her own courses on dirt roads and used sticks and ropes to make hurdles. Once her talents were discovered in high school, Coachman competed on all-black teams throughout the South. Coachman won the gold medal at age 24 and continued her running career thereafter. In total, she won 34 national titles and was inducted into nine halls of fame.

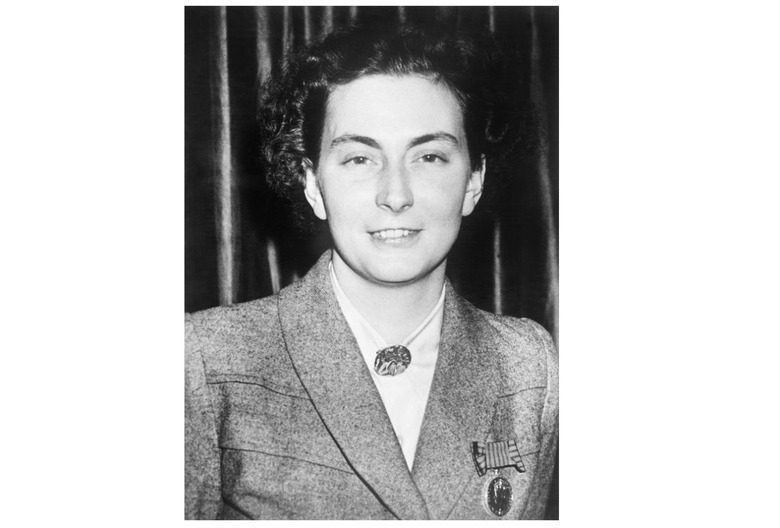

Andrée de Jongh

Andrée de Jongh, nicknamed "Dédée," saved hundreds of lives as a member of the Belgian Resistance during World War II. A practicing nurse, de Jongh was 25 years old when the Nazis invaded Belgium. She volunteered with the Red Cross and began organizing safe houses for Allied soldiers; she organized fake paperwork and wardrobes to keep them well disguised. Later, she and her father developed the Comet Line — a 1,200-mile route over which volunteers smuggled soldiers out of occupied territory. De Jongh personally escorted 118 escapees, and the Comet Line saved over 700 overall. In 1943, she was captured by the Nazis, but due to her young age, they doubted her level of involvement. "I'm as strong as a man," de Jongh is recorded as saying. "Girls attract less attention in the frontier zone than men." Her father was executed; de Jongh was transferred to a concentration camp and survived. After the war, de Jongh volunteered in leper hospitals in throughout Africa until her retirement.

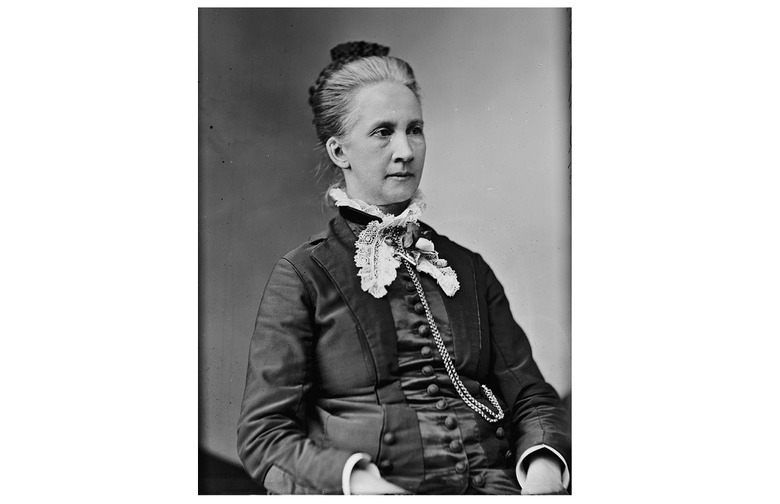

Belva Ann Lockwood

Think the 21st century is when the first female candidates ran for president? Think again. In the 1880s, Belva Ann Lockwood ran twice before women even had the right to vote. As a school headmistress in New York, Lockwood's salary was half that of male headmasters, but her career brought her into contact with Susan B. Anthony, after which Lockwood's philosophies gradually evolved. She returned to school to study law and became one of the first female practicing attorneys in America — though not without facing obstacles. Lockwood was repeatedly denied her diploma and had to petition by mail for admittance to the bar association; she endured lectures from judges on women's inferiority, was sometimes removed from courtrooms and eventually had to petition for her right to practice law in front of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court initially denied her on the grounds of gender, but she eventually became the first woman to argue a case there. She later ran for president and wrote prolifically on women's rights.

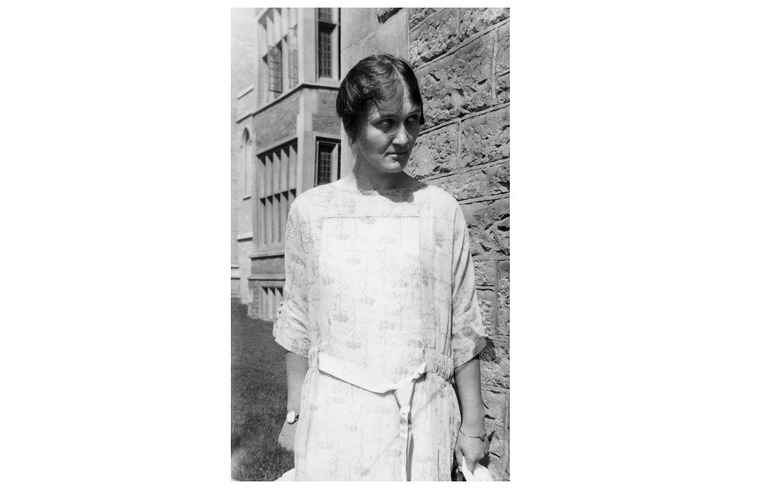

Cecilia Payne

Cecilia Payne outshone the male scientists and mathematicians of her time by discovering the physical makeup of the stars in the 1920s. It had been thought that the sun, stars, and Earth were made of similar materials, but in Payne's doctoral thesis, she showed that stars were actually made mainly of hydrogen and helium. Established astronomers convinced not to publish her findings, but they later discovered she was right — famed astronomer Otto Struve called her work "undoubtedly the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy." Despite her brilliance, Payne spent much of her life working as a technical assistant, though she later became a professor and the first woman to lead a department at Harvard. Her work opened a constellation of opportunities for the female scientists that came after her.

Edith Summerskill

Edith Summerskill worked tirelessly to ensure women in England would be granted the rights they have today. As one of the longest-serving women in Parliament — from 1938 to 1961 — she championed causes such as equal rights, equal pay, availability of birth control and painless childbirth methods, and fair sharing of property between husband and wife. It is largely due to her efforts that the Married Women's Properties Act and the Matrimonial Homes Act (both of which granted financial rights to married women) were passed. Even before her political career, Summerskill had pushed the boundaries of expected career paths for women by becoming a doctor of medicine in 1924.

Huda Sha’arawi

Huda Sha'arawi was one of the earliest feminist activist leaders in Egypt. She was born into an upper class family and married to her cousin at age 13 in 1892. However, after separating from her husband, Sha'arawi pursued her education and began dedicating much of her time to activism. She was the first woman in Egypt to remove her veil in public, a defiant act that became a symbolic event in Egyptian feminism. She hosted women's groups in her home. She brought other women into public, a daring move in a society where many women were confined to the home. Sha'arawi opened a school for girls that taught subjects other than midwifery and homemaking, including science and math. In 1919 she led the first women's street demonstration during the Egyptian Revolution, and in 1923 she founded the Egyptian Feminist Union. Sha'arawi is lauded for laying the groundwork for subsequent feminist movements in Egypt and for Arab women worldwide.

Hypatia of Alexandria

Hypatia of Alexandria, who lived from A.D. 350 to 415, is widely regarded as the first female mathematician whose life was thoroughly recorded. Hypatia's father Theon, himself a scholar, taught Hypatia subjects usually reserved for men, such as mathematics, astronomy and philosophy. Hypatia soon adopted students of her own at a Neoplatonic school in Alexandria, all the while expanding her repertoire as a wise counselor and scholar. She edited and added commentary to many famous texts, including Ptolemy's "Almagest." Alexandria was converting to a Christian city at the time, though Hypatia was pagan, and Christians viewed her as an obstacle to their virtuousness. Hypatia was brutally attacked by a mob of Christian monks, then dragged through the city, stripped naked and beaten to death. Many of the remaining scholars in Alexandria were devastated by her death and chose to leave the city shortly after.

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells was a journalist and anti-racism activist in the late 19th century, when lynching was alarmingly common. Around 100 lynchings were reported each year, many of which were justified by the offenders with the claim that black men were raping white women. But Wells, who had been the target of racism more than a few times personally, knew that this was a lie. She published her research as a booklet called "Southern Horrors," in which she wrote that lynchings were "an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized." Wells wrote tirelessly about violent racism in the South for the paper she co-owned, The Free Speech and Headlight, and was met with violence in return; her newspaper's offices in Memphis were burned by an angry mob, forcing her to move to Chicago. She continued to advocate for black rights and women's suffrage, touring the United States and Europe giving impassioned speeches for change. Wells eventually ran for the Illinois state legislature, but was unsuccessful.

Lois Jenson

Lois Jenson was the first woman to ever file a class-action sexual harassment lawsuit in America. In 1975, Jenson and three other women became the first female employees of Eveleth Mines. Jenson had taken the job out of necessity as a single parent and victim of date rape living on welfare and food stamps. Immediately, the four women endured all kinds of harassment including groping, violent language, threats, stalking and other violent or sexual behavior. The harassment continued unchecked for 10 years, despite consistent reports to management. Stress and the poor conditions of the mines took their toll on the women's health. Jenson had pneumonia on numerous occasions along with high blood pressure and depression. One woman stopped drinking water due to the lack of women's restrooms; she suffered severe dehydration. Pushed to the brink, Jenson filed a class-action lawsuit against Eveleth Mines. The case lingered in various courts for 15 years. During that time, Jenson was ostracized and mistreated; her health declined so severely that she could not return to work. In 1996, a court official found that the women were "histrionic," publicized details about their private lives, and awarded them only around $10,000 each. The decision was overturned on appeal, and eventually the women settled for $3.5 million. Despite the lack of legal success, the suit stands as an inspiration to women still fighting to see justice for sexual misconduct in the workplace.

Martha Gellhorn

Many people know of Martha Gellhorn because of her brief marriage to Ernest Hemingway — but as she famously said, "Why should I be a footnote in someone else's life?" Gellhorn was an inspiring woman on her own. She was one of the first female war correspondents and traveled the globe reporting on everything from World War II to the Arab-Israel conflict for over 60 years. At the time, many thought that reporting on war was a man's job, and due to her lack of accepted press credentials, Gellhorn was sometimes forced to hide in places such as hospital ship bathrooms to get the information she needed. Gellhorn's work changed war reporting and opened new horizons for female reporters, and there is now an award named in her honor: the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism.

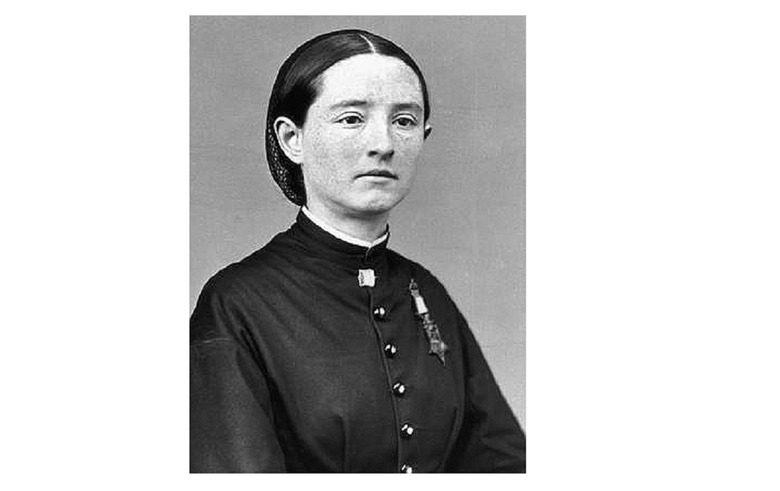

Mary Edwards Walker

Not only was Mary Edwards Walker a medical doctor with her own practice, but she also wore pants —and in the 1800s, that made her a social pariah. Walker was teased for her non-gender-conforming wardrobe as a child, and she was arrested several times as an adult for "masquerading" as a man. During the Civil War, Walker tried to join the Union army as a doctor, but the military refused. Walker insisted on meeting with Secretary of War Simon Cameron, but was again rejected. Walker decided to volunteer to treat wounded soldiers at the Indiana Hospital and continue to ask the government to pay her. They repeatedly refused. Walker even created her own uniform. Her persistence paid off in 1864, when she was hired as an assistant surgeon. During the war, Walker acted as a spy for the Union, spent months in Confederate jail, and was even asked to meet with Abraham Lincoln to share her story. President Andrew Johnson later awarded her the Medal of Honor, making her the first woman in history to receive the distinction. Congress later tried to retract her award in 1917 when they decided only men who'd served in combat could be eligible. But Walker refused to return it, reportedly wearing the medal every day until she died in 1919.

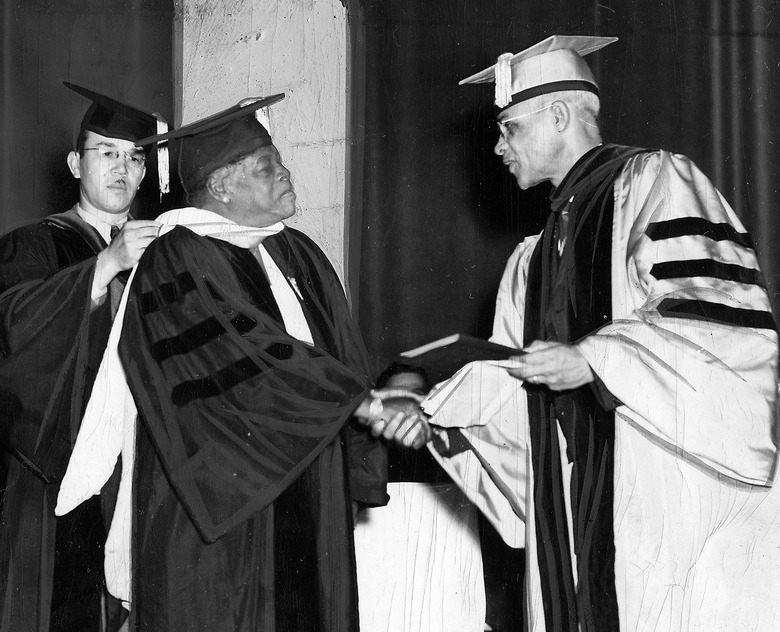

Mary McLeod Bethune

Mary McLeod Bethune is one of the most important civil rights activists of the 20th century. The daughter of slaves, Bethune became an educator and opened a boarding school for African-American students in Florida that eventually became Bethune-Cookman University. Bethune herself was an activist for voting rights, leading voter registration drives despite the threat of violent racist attacks. She was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and was later appointed as director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration by Franklin D. Roosevelt. This made her the highest-ranking black woman to hold political office at the time. She was also a leader of the president's so-called "black cabinet," an unofficial grouping of important advisors to the president. Bethune later became vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP). Later, she was the only woman of color to attend the founding conference of the United Nations.

Rose Marie McCoy

You may not have heard of her, but you've definitely heard her music. Rose Marie McCoy wrote over 850 songs for various artists (including Elvis Presley, James Brown and Nat King Cole) and was one of the most influential voices in the music industry during her career. Yet most people don't know she existed. When McCoy was just 19 years old, she moved to New York City on her own to try and break into the music industry. After hearing two songs she wrote and recorded for Wheeler Records, employers began to seek her out. She landed a job with her own private office in the Brill Building, the epicenter of songwriting during the 1960s. Though McCoy received limited public recognition, her contributions to songwriting have echoes that can still be heard in music today.

Sybil Ludington

Paul Revere is known far and wide for his famous midnight ride, but you've probably never heard of Sybil Ludington. According to a story passed down to her descendants, at 16 years old in 1777, she rode on horseback through the rain for nearly 40 miles (twice the distance of Revere's ride) to warn her father's militia unit of an oncoming attack by the British. Whether or not Ludington was the first to warn them of the attack is unclear, but the men were able to gather and organize, and in the subsequent battle they drove the British back to their ships. George Washington later thanked Ludington for her brave efforts. So the women of history were pretty dang bold — as are the women who continue to do great things today. Here are 15 moms who became huge business moguls.

More From The Daily Meal:

The Strangest Museum in Every State

The Most Patriotic Destination in Every State

The Best Museum in Every State