Common Mistakes Customers Make At Chinese Restaurants

Chinese food is enormously popular among American diners, so much so that Chinese restaurants outnumber all the US outlets of McDonald's, Burger King, KFC, and Wendy's combined. But despite its popularity, Chinese cuisine still remains a bit of a mystery for many American diners, who tend to stick to the same tiny handful of familiar dishes. And for the unacculturated, some of the features of Chinese restaurants, especially the more traditional ones, can be intimidating.

But they don't have to be. As a proud third-generation Chinese-American who grew up in my grandparents' and uncle's restaurants, I'm here to tell you that Chinese dining is not rocket science. No one will throw you out if you ask for a fork or have questions about the menu — restaurant operators understand this is unfamiliar territory for you. But if you want to get the most from what the restaurant has to offer (and earn the respect of your server), you need to avoid a few common tactical and cultural errors. Manage this, and you can enjoy a great Chinese meal and fit in like an expert, even if you can't speak Chinese or use chopsticks.

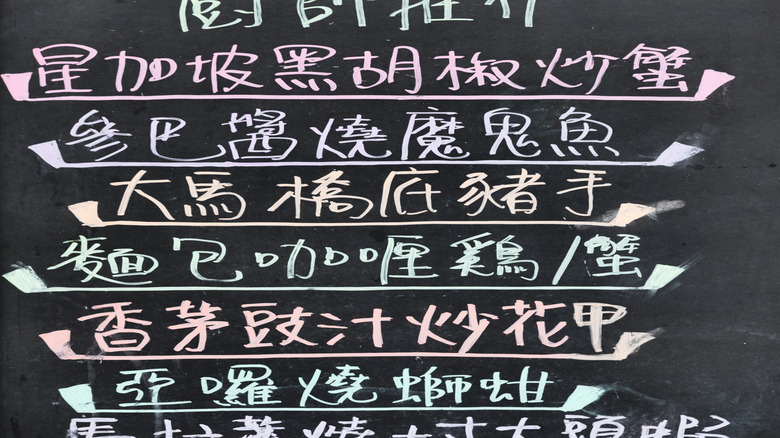

Ignoring the Chinese menu

If you go to a Chinese restaurant in an area with a big Chinese community, you're likely to see two menus on the table: a laminated English menu and a Chinese-language menu, often handwritten. Some restaurants post Chinese-language menus or specials on walls instead. The English menu will have all the familiar favorites, and you'll likely be tempted to choose your whole meal from there. This is a mistake. The good stuff — seasonal dishes and regional specialties — will be on the Chinese menu.

Don't be shy — the menu is there for you too, even if you don't read Chinese. While servers and restaurant owners historically steered non-Chinese diners towards more Americanized dishes for fear of offending them with unfamiliar ingredients or strong flavor profiles, if you're polite and show genuine curiosity about what's on offer, you'll get some great recommendations. You can also look around the dining room and ask about any unfamiliar dish that looks good to you — and you might just find your new favorite dish.

Ordering food just for yourself

In 1993, the Center for Science in the Public Interest released a study (per the Los Angeles Times) that had the Chinese diaspora rolling its collective eyes: A single plate of Kung Pao chicken contained as much fat as four McDonald's Quarter Pounders! The horror! But as many annoyed Chinese Americans pointed out, this showed a fundamental misunderstanding of how Chinese meals work. A restaurant-sized portion of Kung Pao chicken (or any dish) is not meant to be a meal for a single person. Rather, it's meant to be shared by several people as part of a family-style meal, along with lighter, contrasting dishes such as sauteed greens. This strategy is not only healthier, but makes for a more varied and satisfying meal. And let's get real — a meal of nothing but Kung Pao chicken will get really old fast.

So what's the best way to order a Chinese meal? A good rule of thumb is to order one dish per person, along with rice for everyone. It may be tempting to let each diner order their favorite dish for the table to share, but you risk ending up with nothing but deep-fried or super-spicy food. By tradition, the host curates the menu, taking other diners' preferences into consideration while ensuring a balanced assortment of flavors and textures. Meals typically start with a light, brothy soup, followed by a varied assortment of seafood, poultry, meat, and vegetable dishes.

Drowning food in soy sauce

Just because you can do something doesn't mean you should. While many Chinese restaurants leave bottles of soy sauce on tables for diners to use at will, by tradition, it's not meant to be an all-purpose table condiment. It's often used as an ingredient in dipping sauces for steamed or boiled dumplings, steamed chicken, and some plain meat dishes, and you can drizzle a little soy sauce on such dishes if you feel they need it. But it's not meant to be poured over stir-fries or other saucy dishes, or even worse, your rice.

Overusing soy sauce at the table is considered a faux pas for several reasons. First, drowning already seasoned and sauced food in soy sauce not only ruins its flavor but can be seen as an insult to the chef. Seasoning is meant to be completed in the kitchen, and covering your food with soy sauce signals that the chef dropped the ball. Pouring soy over plain rice is not only considered rude, but counterproductive. Rice is meant to be bland and is there to serve as a backdrop for the other dishes on the table.

Asking for sugar for your tea

In almost any Chinese restaurant, you'll get a pot of hot tea almost as soon as you're seated. It's not there just for the sake of tradition — the tea itself is part of the dining experience. Besides being a satisfying drink in its own right, it complements the meal by acting as a palate cleanser between bites as well as a digestive aid. Thus, its mild bitterness is a defining feature (much like the hops in a good IPA), not a bug. So even if you normally like your tea sweet, don't ask for sugar — keep an open mind and enjoy the tea on its own terms.

And once you get used to it, you'll find there's plenty to enjoy. Many restaurants offer several varieties of tea – green, oolong, and jasmine are common varieties. Green tea is a popular all-purpose tea, with a light flavor and aroma that goes well with most foods. Oolong is a darker and stronger tea that's a good match with richer meals. And jasmine tea, as its name implies, is light and floral and goes well with delicately flavored dishes — it's a popular accompaniment to dim sum meals.

Expecting dim sum on the dinner menu

If you're a serious fan of Chinese food, you've probably enjoyed dim sum dishes (South Chinese small plates), such as steamed or fried dumplings and cakes or small portions of meat. They are traditionally brought to the table by roaming servers with rolling carts, who stop at each table to show their offerings. For most Western diners, dim sum feels like lunch or dinner food. But by Chinese tradition, dim sum is a breakfast or brunch meal (as well as the hangover breakfast of champions), which is why the carts at traditional dim sum restaurants stop rolling by early afternoon.

So while a plate of dumplings may sound like a great appetizer, unless you're dining in a restaurant that caters to non-Chinese diners, don't expect to find them on a dinner menu. The Chinese dining tradition doesn't include a separate appetizer course, but some appetizer-adjacent dishes make common appearances early in the meal (after the soup course and before everything else). A popular choice in traditional banquets is a cold meat platter featuring several varieties of cold-cured or seasoned meat (such as Chinese-style ham, braised beef, and/or smoked fish) in small pieces.

Missing out on regional specialties

Chinese food is about way more than just sweet and sour pork and beef with broccoli. While these Chinese-American favorites have become classics in their own right, if they're all you've tasted, you haven't even begun to familiarize yourself with Chinese cuisine. It's worth remembering that China is a huge, geographically and culturally diverse country whose landscapes range from deserts to coastal estuaries to icy mountains. And its food is just as varied as its landscapes.

So if you enjoy Chinese food but haven't explored beyond the standard takeout menu, you're missing out. An easy way to expand your horizons is to seek out restaurants featuring China's regional cuisines. Fortunately, they're not hard to find in major cities, and even college towns with good-sized international student populations are likely to have a few. If you're a fan of Cantonese dim sum, you might want to try heartier Northern Chinese dumplings such as potstickers. Or you may enjoy rustic Hakka cuisine, with its focus on meats and preserved vegetables, or the spicy, smoky dishes of Sichuan. If you're lucky, you may find restaurants featuring the dishes of China's Muslim population, which include beef kebabs, hearty noodles, and breads seemingly designed for dunking.

Trying to reinvent menu items

We won't lie: Chinese restaurants can be minefields for picky eaters. If you hate it when your meat and veggies touch each other, you're going to have a tough time in a traditional Chinese restaurant — most dishes feature a combination of protein and vegetables cooked together. And if you have food sensitivities or dietary restrictions, a traditional Chinese meal may be rough for you unless you do your due diligence and order with care. For instance, even soy sauce, an essential Chinese pantry ingredient, is a no-go for the gluten-intolerant.

Some diners try to avoid problematic ingredients by requesting special orders, such as stir-fries with the sauce on the side. Unfortunately, this probably won't go well. Sauces in Chinese stir-fries aren't cooked separately from the other ingredients, but built up in the wok as the dish is cooked, so the sauce can't be separated from the rest of the dish. And even if the restaurant tries to accommodate you by whipping up a freestanding batch of sauce, it won't taste right, since it lacks the flavoring it would normally get from the other ingredients in the dish. Asking for ingredients to be added or omitted from a dish may or may not work, but it is always considered bad form.

Standing your chopsticks in your rice bowl

For those unfamiliar with East Asian dining traditions, one of the most puzzling aspects of the Chinese table is what to do with chopsticks. How do you hold them, and how are you supposed to use them over the course of the meal? You can find plenty of online tutorials on how to hold and control them (it takes only a few minutes to learn), and while eating, you use them pretty much the way you'd use a fork, to pick up food on your own plate. To help yourself from a communal plate of food, use the serving utensil provided, or use the broad end of your chopsticks, not the end you were eating with.

But just as you'll have to set your fork down several times in a Western meal (for instance, when taking a drink), you won't always be holding your chopsticks during a Chinese meal. More formal restaurants will provide chopstick rests, but they're not common in U.S. Chinese restaurants. Instead, simply lay them together on your plate. What's never okay, however, is stowing your chopsticks by impaling them in the rice in your rice bowl or laying them on top of your rice bowl – both are considered bad luck. Sticking chopsticks in your rice in particular is considered unlucky, since it evokes the appearance of the incense sticks used in funeral rites — and in Chinese culture, evoking death at the table (or anywhere but a funeral, for that matter) is always bad luck.

Expecting all Chinese food to be cheap

Chinese restaurants in the U.S. have long had a reputation as places to go for a cheap meal. There are historical reasons for this: The first Chinese restaurants in the U.S. emerged in the mid-19th century, when enterprising immigrants opened simple, affordable eating houses to serve their peers (as well as any poor white laborers adventurous enough to try them). Later, Chinese restaurateurs faced difficulty acquiring bank loans due to racist policies, so they had no choice but to open modest eateries that operated on shoestring budgets.

And while casual, affordable Chinese restaurants are still common, upscale Chinese cooking exists, and yes, it's very much worth the investment. Today's Chinese immigrants are more likely to be senior executives than railroad laborers, and they're willing to pay for the same quality of Chinese food they enjoyed back home — and restaurateurs are more than happy to provide it. So if you go to a Hong Kong-style seafood restaurant and see tanks of live crabs and lobsters in the dining room and bottles of French champagne at the bar, expect to pay the same for them as you would in a Western-style seafood restaurant.