How To Tell If A Recipe Is Bad Before You Make It

It has happened to us all at one point in our culinary lives. We have hunted for the perfect recipe for days for a chocolate cake we plan to make for a special occasion. After combing through the recipe, we went to the store to obtain all the necessary ingredients, spending a pretty penny on the right kind of fair-trade organic chocolate. We carefully lay out our ingredients, following the recipe as precisely as possible. Everything appears to come together smoothly as we place the cake in the oven that we preheated to the temperature on the recipe.

We wait for the cake to bake, anticipating the glorious final result. And then it happens — the timer beeps, we look into the oven, and we discover that something transpired between the moment we put the cake into the oven and now. The cake never rose. It is dense, and the center is still gooey. Now we have no cake and must scramble to get a box mix to save the day, ego and wallet deflated.

It is disappointing and infuriating to have a recipe not turn out as hoped. However, there are some red flags you can keep an eye out for when selecting a recipe to ascertain if there is an inherent flaw in it. Knowing what to look for can help spare you the time and money lost in a recipe failure. Let's look at some red flags that can make or break a dish.

Preparation times seem unrealistic

We have always been skeptical about recipes that dub themselves as "fast and easy." According to whom? Generally speaking, most home cooks do not have the same knife skills, intuitive ability to know what to put into a pan in what order, or experience necessary to assess that something is ready without following a recipe point by point that professional chefs have. When a recipe seems too good to be true, like a quick risotto, for example, it probably is.

Don't be fooled by the preparation time listed on the recipe. It is simple to look at the basic preparations involved and determine that there is no way you can chop all of the vegetables required in less than five minutes. Who are they kidding? It is also clear that certain foods cannot get cooked in the allotted amount of time. Let's take the risotto example — arborio rice cannot get coaxed into cooking faster than it can absorb water. We all want to believe that delicious meals can be on the table in under 30 minutes, but this may be unrealistic.

Measurements for baking are in cups, not grams

Ask any professional baker worth their salt how they measure their dry ingredients for a recipe, and most will tell you they do so with a scale. There's a simple reason for this — accuracy. Measuring cups are wildly inconsistent, as are the humans doing the measuring. There are as many ways to scoop out a cup of flour as there are people. Some scoop, press down, then level. Others scoop, shake, then level. Still others sift the flour into the measuring cup and then level the flour. And the problem is you have no way to assess how the recipe developer measured their flour. The result is too much or too little flour, which will make or break your cookie, cake, pie, biscuit, or quick bread recipe.

Baking is a science, and as a result, the precise ingredients and proportions are non-negotiable. For a recipe to be reproducible over and over again, precision is elementary. To illustrate this, Bake School cross-referenced several different cookbooks to see how many grams of flour were in a cup. When examined, the average ranged between 88 and 145 grams of flour per cup, which may mean the difference between a fluffy cake and a hockey puck. Additionally, when recipes are given in ratios, as in 1:2:3, or 1 part fat, 2 parts liquid, 3 parts flour, the amounts yielded by weight versus volume are wildly different. The bottom line — when baking, seek out recipes given by weight rather than volume.

Recipes are not blind tested

Recipes are a dime a dozen on the internet. Anyone can create a website or blog and start pumping out recipes. But are these recipes foolproof? It's hard to say. Recipes from reputable websites are generally blind tested, meaning a team of individuals ranging from amateurs to professionals will make the recipe several times, each time noting any observations about things that may not have worked the same way, from ingredients to equipment, to cooking methods, to cooking time. Sometimes a website will indicate that a recipe is courtesy of a chef but then lists the staff involved in publishing the recipe. That's a relatively good bet that you are getting a well-researched recipe, but not a guarantee. Other times, independent chefs may do their blind testing themselves. There's nothing wrong with that either, as long as they check and recheck that their recipe works.

Ultimately, even recipes that have been blind tested may still have inconsistencies, ranging from the ingredients you have at your disposal to the type of blender you have. It just cannot be avoided. And if you are unsure about the amount of research that has gone into a recipe, it is okay to refer to the reviews. Take these with a grain of salt, however, as some people will give a good recipe a low rating based on not following it precisely or not understanding how to deglaze the pan correctly.

Instructions are not broken down into clear segments

Recipes should be conceived of as an outline for creating a dish. Outlines always get divided into sections, each with a title and subsections, where appropriate. A properly written recipe should uphold similar standards, carefully dividing one step from another. Doing so ensures two things: one, that it is as easy as possible to follow, and two, that the person following the recipe doesn't accidentally skip any steps. A recipe that reads like a run-on sentence or has all of the steps lumped into one long paragraph indicates the developer hasn't adequately evaluated how best to convey the individual steps required for the recipe to get correctly executed.

And if a recipe involves multiple components, like a sauce, a meat, and a starch, each must be separated with its own steps indicated. If there is overlap in preparation, for example, "while the sauce is cooking, pan-sear the meat," this should get clearly noted so as to guarantee that all the ingredients get done at the same time, with none of the components of the dish left waiting for the rest to get finished.

Ingredients are not clearly broken out

It may go without saying, but just as instructions to a recipe need to get broken out into sections, so should ingredients. If there are multiple components to a recipe, like sauce, meat, and starch, the ingredients for each segment should be listed separately, with titles for each section delineated. If items get used multiple times within the same recipe, say once at the beginning of cooking and once later on in cooking, the ingredient should be listed twice, indicating where in the dish that amount of the item belongs.

An example of this may be in a stir-fry. Green onions are often used in stir-fries and cooked with the meat and vegetables. They are also almost always used in raw format as a topping or garnish, with the juxtaposition of the two being integral to the flavors and textures being authentic. As such, green onions should get listed twice, at the beginning of the ingredients and the end, noting any differences in how they are prepared and how much to use at each stage.

There is no introduction to the recipe

One of the telltale signs of a well-thought-out recipe is that there is a story to it. It need not be a long tale about how the recipe author used to enjoy the dish with their family when they were a child every Christmas, although it could be. It can be as simple as an anecdote about what the recipe author enjoys about this particular recipe, with comments about any complexities or difficulties they may have encountered in perfecting the recipe. This type of introduction tells us that there was time and care invested into how this recipe turns out and how the recipe author wants others to experience it.

The more trials and tribulations included in this introduction, the more confident we are that the recipe has undergone adequate testing to be reproducible. Recipes without an introduction leave us skeptical. We want to see the personality of the recipe developer in their introduction. Food is all about humanity. It connects us. The presentation of the recipe is the recipe developer's chance to make that connection.

The recipe doesn't indicate salted or unsalted butter

The type of butter used in a recipe may not matter very much where cooking is concerned, but it is critical where baking is concerned. Remember, baking is a science. Every ingredient used in a cookie, cake, pastry, or quick bread has been measured to ensure that the flavor and texture of the final baked good are precise. When a recipe for a baked item doesn't specify what kind of butter to use, salted or unsalted, this leaves us skeptical.

Salted butter typically has ¼ teaspoon of salt added per ½ cup of butter, although this amount is not regulated in any capacity and may vary by manufacturer. Additionally, salt acts as a preservative, making the shelf life of salted butter longer than unsalted butter. When baking, the freshness and salinity of butter matter because you do not have the opportunity to taste the batter before it has finished baking, which is why most recipes for baked goods will specify unsalted butter.

More importantly, butter influences the texture of a recipe. Salted butter has a higher volume of water than unsalted, anywhere from 10% to 18%. Because gluten requires precise moisture content to form, any extra moisture can adversely impact gluten formation. This ultimately affects the texture of your baked item. When in doubt, use unsalted in your baked goods unless otherwise specified. If all you have on hand is salted butter, and the recipe calls for unsalted, decrease the amount of salt by ¼ teaspoon per ½ cup of butter in the recipe.

There aren't any notes

Unlike the introduction, notes are inserted between sections of the recipe instructions or at the end of the recipe. These notes often intend to offer substitutions, optional ingredients, or guidelines on how to adapt a recipe for a particular audience, like gluten-free or vegan. The memos may also include things to watch out for, like the color of a baked good or the texture of a vegetable in a dish. And finally, notes will often include things like what kind of baking dish to use or if there is a preferred type of blender for the recipe.

All of these things matter. They provide information that can make or break how your recipe turns out that may have nothing to do with the ingredients or even the step-by-step instructions. Again, these aren't necessary, but seldom do we see a recipe that doesn't have something additional to add at the end.

Weights or exact sizes are not indicated for vegetables

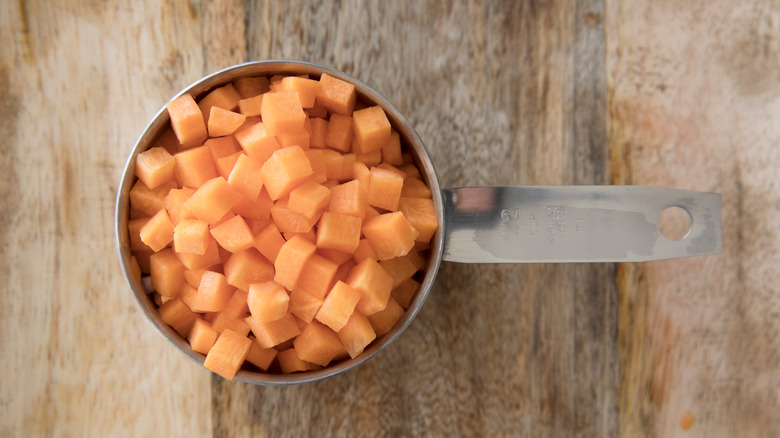

If you have ever been to a farmer's market, you may have seen a zucchini or butternut squash over a foot long. While this isn't average, it illustrates the vast diversity in size a vegetable may have. Granted, most grocery stores opt to sell produce that is uniform in size, but it should be noted that a recipe with ingredients listed as "one carrot, diced" or "one large eggplant, sliced" is not an accurate recipe. Imagine using a carrot from the store versus a farmer's market monster carrot? The difference in size can radically change the amount of liquid and other seasonings required in a recipe.

It is crucial to indicate the weight or measurements for vegetables, for example, a "2-pound butternut squash, peeled and chopped" or "1 cup of diced carrots." This type of ingredient description is a much more accurate way to ensure the recipe will turn out the same every time. This accuracy in a description also applies to grains and legumes, which should get noted as cooked or uncooked, with the proper weight or volume indicated on the recipe.

There are ingredients missing

Before you decide to use a recipe, read through the entire recipe from beginning to end, including ingredients and instructions. If any items are missing from the ingredients list but appear on the instructions or are absent from the instructions but appear on the ingredients list — skip the recipe.

This type of thing happens more often than you would imagine, particularly with ingredients that chefs assume people know to use, like salt and pepper, or with recipes that contain a long list of ingredients or are more complex. It's not necessarily a reflection of the culinary ability of the recipe author or even the efficacy of the recipe. However, without complete and accurate information, you cannot recreate the recipe successfully, nor is it possible to effectively put together a grocery list or gather your ingredients. Again, this one seems like a no-brainer, but it is more common than you might expect.

Ingredients or instructions are in the wrong order

One of the fundamentals of sound culinary technique is the process known as "mise en place." This fancy French term translates to "putting in place," which refers to preparing and organizing all of the ingredients you will need for a recipe ahead of time. Mise en place is critical for several reasons, including efficiency, eliminating food waste, and ensuring you do not inadvertently forget any ingredients in your dish. It is why ingredients in a recipe must be listed in the same order as they appear written in the instructions, including those used more than once.

Mise en place may include the following steps: washing and cleaning your fruits and vegetables, properly cutting them, preparing meat as needed, pre-measuring ingredients, sorting all components into individual bowls, and pre-setting any equipment or utensils you need. All of this should get placed in order in a way that makes sense for you in your kitchen and in a way that will be easy for you to follow as you proceed through the recipe. We generally use small ramekins to pre-set all of our ingredients or will put all of the items that go into a dish simultaneously (like spices) onto the same plate. This operation may sound like a laborious extra step that will create a pile of dishes to wash, but trust us when we say that it will make the cooking process infinitely more streamlined and your capacity for success far higher.

Special equipment needed is not highlighted

We admit that we have a bit of an addiction to kitchen gadgets. Any special equipment needed for a recipe is already on hand in our kitchen. But this is not always the case for those who do not cook frequently or cannot afford more expensive equipment. That said, recipes must include notes about any special equipment required. And, where applicable, comments about alternative methods of accomplishing a task are always welcome.

Let's give a couple of examples. Making soup with an immersion blender is infinitely easier than doing so with a blender. Many soup recipes will say "purée the soup using an immersion blender" because you can do so while the soup is hot. Without an immersion blender, the soup can still be made using a regular blender or food processor, but not before cooling the soup thoroughly before puréeing to avoid steam collecting in the blender or food processor, which can potentially cause a nasty burn.

Another example might be a recipe for potato chips. Slicing potatoes with a mandoline slicer is infinitely faster than any other method for thinly slicing potatoes. However, many people cannot afford to get one or are afraid of losing a finger using one. An alternative might be using the slicing feature of a box grater, which takes longer but is effective, or thinly slicing the potatoes with a sharp knife. Again, special equipment can save time but may not be necessary to cook a dish.

Is the type of salt used and amount indicated?

It may sound hyperbolic, but few ingredients are as critical to the success or failure of a recipe as salt. Don't believe us? Just consider the number of different types of salts available for purchase in the grocery store. From simple table salt and kosher salt to flaked salts and Himalayan pink salt, it's hard to know what salt to use where. For this reason, the type and amount of salt must get listed on a recipe ingredients list. As a general rule of thumb, salts with smaller crystals, including kosher, table, and sea salts, are best for cooking and baking, as they dissolve easier. Flaked salts and specialty salts get reserved for finishing salts, added at the end of cooking for a pop of flavor.

But not so fast — where baking is concerned, the salt debate is even more nuanced. Because salt can influence everything from flavor to texture to the ability of eggs to bind your batter together, the type and amount of salt used are even more critical. Since we typically measure salt by volume, it is crucial to understand that the weight of a given volume of salt can vary widely by type and brand. For example, 1 tablespoon of table salt weighs 20 grams, 1 tablespoon of Morton kosher salt weighs 15 grams, and 1 tablespoon of flaked sea salt weighs 10 grams. These are substantial variables in something as precise a science as baking. The bottom line — always use the salt indicated on a recipe for the best results.

Cooking temperatures aren't clearly indicated

Recipes should always include exact oven temperatures. They should also state when to preheat the oven in the instructions. But what is less frequently clearly stated is the cooking temperature for items prepared on the stovetop. A recipe noting you should "pan sear the filet" or "sauté the vegetables" is unclear. Should the burner be low, medium, or high? Does the temperature need to be adjusted at any point during cooking? For example, should the heat be reduced to low so the soup can simmer? We need to know precisely when and at what temperature to set the burner at all stages of cooking.

We will take this one further to include cooking temperatures for meat. While specific USDA guidelines exist for safe minimum internal temperatures, a recipe should clearly state the required internal temperature for the recipe to turn out accurately according to how it got designed. Always follow these temperatures by testing with a meat thermometer. Recipes that say "rare," "medium," or "well-done" without specific temperatures are not clear enough.

Is there a clear indication as to when the recipe is done?

Most recipes will include at least an approximate cooking time based on the equipment they tested their recipe on. However, cooking times can vary greatly depending on your specific stove or oven, making it critical that other indications of doneness get listed in the recipe. Where meat is concerned, safe internal temperatures should be indicated. For soups or stews, textures should be noted, like fork tender or until the vegetables begin to fall apart. For still other recipes, elements like the color, smell, or even sound made by the dish (yes, foods make noise) can be listed.

If a recipe involves baking something — including desserts, roasts, or casseroles — exact temperatures and textures should get noted. For example, many cakes and quick breads include a note about inserting a toothpick into the center, which should be clean when removed to ensure doneness. Others will state that the edge of the cookie should be golden brown while the center is still slightly soft to the touch. Any type of descriptive that involves your five senses or exact temperatures is necessary for you to be able to execute the recipe correctly.