A Conversation With Aubert De Villaine

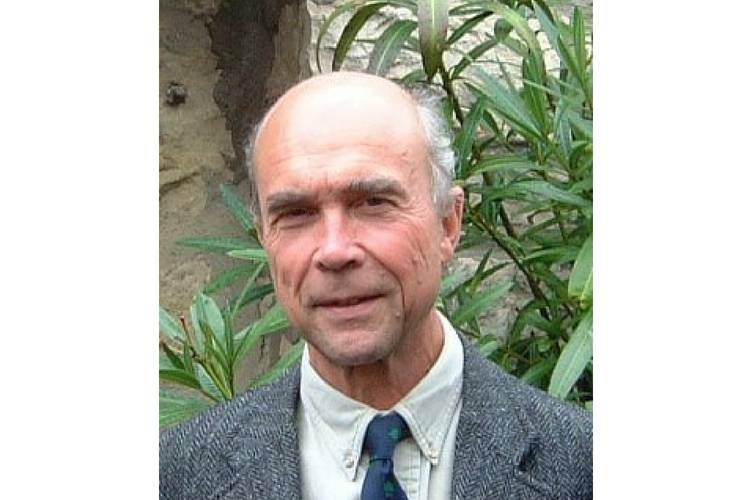

At 79 going on 80, Aubert de la Villaine, the director of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (DRC), which produces some of the world's most expensive and rarest wines, is still going strong, running up and down cellar stairs like a teenager, just to keep ahead of schedule.

In November, just after the annual Hospices de Beaune charity wine auction festivities, I sat down opposite de Villaine at the domaine's headquarters in the small town of Vosne-Romanée to discuss a range of topics spanning de Villaine's many years in the wine business, and reaching into the future as well. I found him friendly, very thoughtful, and quite precise.

In concert with the Leroy/Roch family, de Villaine oversees the DRC's collection of eight labels produced from 69 acres of grand cru vineyards which they either own a part of, in the usual Burgundy style, or all of (these are the rare so-called monopoles). They are Corton, Echézeaux, Grands-Echézeaux, La Tâche, Montrachet, Richebourg, Romanée-Conti, and Romanée-Saint-Vivant. A single bottle of any of these, depending on the vintage, can fetch thousands of dollars. De Villaine also owns, with American relatives, a portion of HdV Wines in Napa Valley and, with his American wife, Pamela, the A&P de Villaine winery in the Burgundian commune of Bouzeron, which produces white wine from the aligoté grape.

Just after we sit down, I make the mistake of referring to the domaine as "DRC," a common abbreviation in the wine world. "I don't like that term," de Villaine pleasantly interrupts. "I'm still fighting that acronym." However, using "Romanée-Conti" as a shortened name would confuse the domaine with one of its parts, and using the total name is a mouthful, so eliminating use of that term is probably one battle that even de Villaine will not win.

Although he grew up west of Beaune on a cattle farm, his family had inherited parts of several Burgundy vineyards that had not yet achieved the prominence they have today. As a young man, de Villaine spent time in the U.S. in the wine trade, working for both the New York-based importer Frederick Wildman & Sons and later in California for Almaden. During this time, he met Robert Mondavi, who at the time was still working with his brother, Peter, at the family's Charles Krug winery. De Villaine was impressed. "Robert had a clear vision of what he wanted to do," de Villaine says — though on reflection, he adds, "I think he tried to do too much." Otherwise, he says, "the winery might still be in the family." (Constellation Brands bought it in 2004.)

De Villaine came back to Burgundy in 1964 and was put to work by his father learning the business side of running a winery while he studied enology. In 1974, he rose to become DRC's co-director and started the long process of turning the vineyards into organic and eventually biodynamic production. Those early years were not easy.

"In the 1970's and 1980's," he tells me, "Burgundy and Domaine Romanée-Conti were not what they are today. It was hard work for us. I carried bottles of our wines in my luggage on trips to England and America trying to get orders." In 1979, he chose Wilson Daniels as his American importer, a role that company still fulfills.

"After [wine critic Robert] Parker abandoned us, we gradually got back to fundamentals," de Villaine says, referring to the wine-rater's decision in 1993 to no longer personally cover Burgundy wines, seeming to prefer those of Bordeaux. (Parker has since admitted that he perhaps stepped on too many Burgundian toes; he even had to settle a defamation claim with one producer.)

"We have greatly improved in the past the 20 to 30 years in both vineyards and cellars," de Villaine says. With a few exceptions, he does not believe in ignoring modern technology. Rather, he is an advocate of using it in the vineyard and the cellar in order to more easily obtain the same or similar results he had earlier achieved using traditional but more labor-intensive practices. For example, he explains, "Before, we cooled the grape must with blocks of ice or by taking it outside on a cold night, but today the new cooling systems are a better answer." Similarly, newer, lighter tractors make tasks not manageable with a horse achievable while minimally impacting the soil. De Villaine does not, however, use mechanical sorting of grapes. "I like to pick as ripe as possible," he says, "and for that I prefer the human touch."

He pays close attention to clonal selection, too. "We started 10 years ago in association with 39 [Burgundy] domaines to do selections toward safeguarding the pinot noir family," he says. "When we do selections, we are careful to keep separate types that mature late and types than can adapt to earlier and earlier picking." De Villaine notes that years ago he harvested around October 5. Today, September 15 is a more usual picking date.

De Villaine was ahead of the curve in adopting organic principals, and, in 2000, he went further by beginning the conversion to the more stringent biodynamic practices, which he successfully completed in 2006. "For me, biodynamics is not a religion but is more about getting concentration and finesse [in the wines]. I think what we have gained is finesse and maturity because of a better balance between yield and terroir."

"One can always do better," he explains. "There is always progress. There is never an end."

De Villaine was a leader in getting the Côte d'Or region designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site, which happened in 2015, recognizing 1,247 tiny, singular vineyards or climats that compose the region. "At first, people were afraid there would be too many constraints," he says, meaning that they feared limitations on what could or couldn't be done in recognized areas. "But it's important to remind people we have a long history, and that this is a very special place. We're not freezing it; we're protecting it."

There is one Domaine de la Romanée-Conti wine you won't be able to buy, no matter your budget or your connections. After we have spent about an hour talking, de Villaine says, "You can't leave without some liquid on your lips." We walk across the street to the cellar in the fading afternoon sun. "Let me show you something you've not had," he says, and disappears among the barrels and stacks of bottles. He comes back with an unlabeled bottle he identifies as a 2008 Bâtard-Montrachet, a chardonnay of which he produced just a couple of barrels. "We only drink this here at the winery for family and guests," he explains as he opens it. It is, of course, a delightful wine. As we taste, de Villaine notes, "A little botrytis gave the wine some opulence. Bâtard is a little between a great lady and a beautiful lady."

When we are through tasting and talking, he leaves the bottle behind. "The staff will like this," he says.

(Travel expenses for this story were paid for by the Bureau Interprofessionel des Vins de Bourgogne.)