Facts You Should Master About Pasta Terminology

While pasta is associated with Italy and Italian culture, according to DeLallo, the earliest evidence of pasta is actually attributable to the Shang Dynasty of China over 3,000 years ago. Early forms of pasta were also discovered in ancient Greece and Africa. Pasta began to appear in Italy during the 4th century B.C. as part of the Etruscan civilization. Archaeological evidence of pasta-making tools has been unearthed from an Etruscan tomb, putting to rest the legend that Marco Polo introduced pasta to Italy.

The evolution of pasta as integral to Italian identity can be traced back to the Renaissance. This was a period during which pasta became widely available in Rome and Florence. Diversification of shapes and styles of pasta — as well as the introduction of dried pasta — continued throughout the 19th century, by which point pasta had become a signature staple of the Italian diet and lifestyle. Italy boasts over 500 different shapes of pasta, each designed to be paired with a particular sauce.

Per Share the Pasta, pasta came to the U.S. along with the colonists from England. The first macaroni machine was introduced in 1789 by Thomas Jefferson, who discovered it while serving as an ambassador to France. During the Industrial Revolution, commercial pasta manufacturing became possible with the establishment of the first pasta factory in Brooklyn in 1848. Today, pasta continues to enjoy worldwide popularity thanks to its versatility, nutritional value, cost effectiveness, and simplicity. With the ubiquitous availability of pasta of all kinds, understanding basic pasta terminology is a critical skill to ensuring that you nail every pasta recipe you try.

Al dente

Chefs and pasta manufacturers alike recommend that pasta be cooked "al dente," which literally translates to "to the tooth," as noted by MasterClass. From a practical perspective, the texture of cooked pasta should be slightly chewy without being crunchy. While this appears to be a simple thing to achieve, it is actually more complicated than it sounds. The safest way to ensure that you do not overcook your pasta is to begin tasting it two minutes prior to when the instructions say it should be done. Al dente pasta will have a tiny white dot in the center of the noodle when you bite into it. This is a good indicator that it is ready to be strained and served.

Barilla offers an additional reason as to why pasta should be cooked al dente that is nutritional in nature. They note that pasta has a low to medium glycemic index regardless of what kind of wheat is used to produce it. What this means is that it is digested less rapidly than other carbohydrates, helping to increase fullness and decrease hunger. Overcooking pasta can influence the glycemic index negatively. Cooking it al dente is the best way to ensure maximum nutritional value of the pasta.

100% durum wheat semolina

Semolina flour is a high-protein flour milled from durum wheat, per Healthline. The second most cultivated wheat strain on the planet, triticum turgidum has adapted to grow particularly well in the climate surrounding the Mediterranean sea. This makes it the most common wheat utilized in the production of pasta in Italy and North Africa. While nutritionally similar to its cousin triticum aestivum — which is commonly used to bake bread — there is a distinct difference in texture which is what makes flour labeled "100% durum wheat semolina" ideal for making pasta. Because it is a harder wheat, it requires more milling to turn it into flour. This makes it a less starchy flour which doesn't ferment or rise as well. However, what it lacks in elasticity it makes up for in extensibility, meaning it can be stretched without breaking.

Dagostino Handmade Pasta goes on to note the ways in which semolina flour, in particular, can be a nutritional powerhouse compared to standard all-purpose refined flours. Aside from being high in protein and fiber, it is high in B vitamins — particularly folate and thiamine — which can aid in converting food to energy. Semolina is also rich in a particular kind of iron, called non-heme iron, which can help prevent anemia. Consumer Reports adds that eating cold semolina pasta can be a good source of resistant starch, which is necessary for maintaining the healthy microbial balance in the gut. This has been linked to everything from blood sugar maintenance and weight loss to resistance to pathogens and increased immune system health.

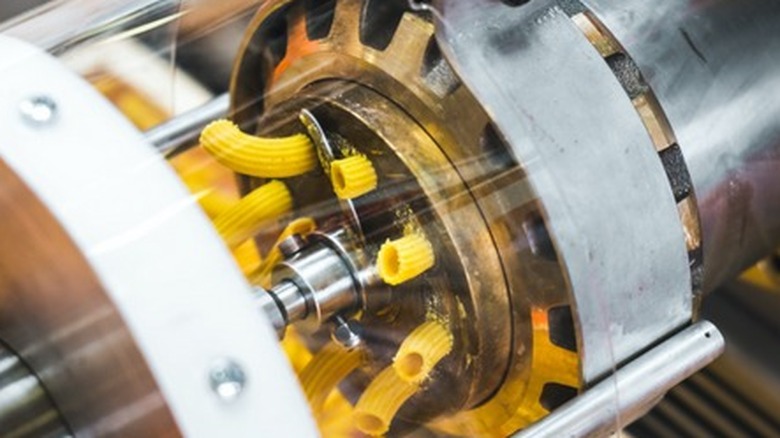

Bronze-die pasta

Bronze-die pasta — also known as bronze-cut pasta — refers to the material that the extruder (used to create the unique shapes and sizes of pasta in commercial production) is made of, per Patagonia Provisions. Modern extruders have transitioned to utilizing cheaper and more efficient Teflon to extrude pasta. While the Teflon allows for pasta to be made faster, the finished product is inferior to classic pasta made with a bronze-die extruder. Teflon extruders yield a slick, smooth-textured pasta as opposed to a pasta with a porous, rough surface. The result is a pasta that doesn't allow for sauces or oils to stick.

Dagostino Handmade Pasta adds that while the texture of the bronze-cut pasta may seem to be a liability in terms of absorbing more liquid in the cooking process, this is not actually the case. The high-protein semolina flour creates protein bonds that don't noticeably increase the surface area of the pasta, which makes the cooking time virtually the same as Teflon-cut brands. Ultimately, the cost to quality ratio isn't high enough to warrant compromising on the superior product, particularly when preparing pasta dishes where the sauce is the star of the show. Next time you are preparing a lighter sauce without a lot of added starch or thickening agent in it, be sure to purchase a pasta with the words "bronze die" on the package to maximize the sauce-to-pasta quotient in each and every bite.

Slow-dried

Slow-dried pasta is pasta that is allowed to dry naturally as opposed to machine-dried in high-temperature microwaves, according to Dagostino Handmade Pasta. Their process involves cutting the pasta into the appropriate shape and transferring it to a temperature-controlled drying cellar which prevents the pasta from spoiling while allowing it to dry slowly. The pasta is considered to be artisanal because it takes longer to create than mass-produced pasta, and is therefore more expensive.

Dagostino maintains that the higher cost is worth it. The artisanal slow-dried pasta absorbs water more consistently, allowing it to cook to the perfect al dente texture much more rapidly. Gustiamo agrees, but goes on to assert that slow-dried pasta is also healthier than mass-produced pasta. The reason for this has to do with the way in which high-heat drying affects the gluten in the pasta. When the gluten is exposed to high temperatures, the gluten mesh constricts. This makes it harder for us to digest the pasta than traditionally made slow-dried pasta, where the gluten remains unaffected by the drying process.

IGP vs. DOP

Certification of Italian cuisine is something that came about in the mid-20th century, according to Eataly. The popularity of Italian food soared — making navigating tradition, culture, and quality something of a concern. In an attempt to protect the legacy of Italian culinary prowess, Italy began working with the European Union to establish regulations that could ensure their history of fine-quality food would continue. Two different certifications evolved out of this mission: the Indicazione Geografica Protetta (IGP), and the Denominazione d'Origine Protetta (DOP). The IGP certifies the place or region where a food is produced, while the DOP guarantees how the food is produced is consistent, from production to packaging.

Pasta di Gragnano IGP is a good example of the importance of this type of certification, as per Wine and Travel Italy. This unique curly pasta is only produced in a 15-square-kilometer area on the Sorrento Peninsula of Italy. The unique microclimate here is what makes this pasta so special. As Eataly Arabia notes, the area is flanked on one side by the sea and on the other by the Lattari Mountains. The temperature and ample sun makes it the perfect environment to dry pasta. And the unique limestone-deficient spring water indigenous to the area gives the pasta a distinct flavor.

This pasta has been made in the same region for over 500 years and has been the primary industry for the inhabitants of the area for generations. Known as "white gold," this pasta obtained IGP certification in 2013.

Gnocchi

The name "gnocchi" stems from the antiquated Lombard word "knohha"— which translates to "knot" — referring to the shapes of these little dough balls, per Eat Like an Italian. A precursor to pasta, early renditions of this dish date back to ancient Rome and were made with everything from cornmeal and flour to stale bread and starchy vegetables. As differing as the base ingredients can be, the ways of cooking and topping these bundles of deliciousness are even more diverse. Regional specialties abound, telling a story of a food culture as varied as the people of Italy.

As our sister site Mashed notes, potato gnocchi didn't arrive in Italy until the 16th or 17th century, when the New World staple was introduced to Italians by Spanish explorers. The potato grows best in the northern regions of Italy, making it a specialty of that area. In fact, the city of Verona has an entire festival devoted to the dish, which occurs the last Friday of Lent during the Verona Carnival. The Bacanal del Gnoco is yet another example of how integral the dish is to the culinary legacy of Italians.

You have the freedom to prepare gnocchi in a myriad of ways, from boiling to baking to frying. You can also top them with any variety of sauces, from a simple tomato sauce or pesto to a more robust meat sauce. However you prepare them, make sure not to over or undercook them, as you run the risk of them becoming too dense and chewy or completely disintegrating into the cooking liquid.

All'uovo

The term all'uovo refers to egg pasta, per Sogno Toscano. This type of pasta is most commonly found in the northern regions of Italy, particularly the Piedmont. Examples include the flat, sheet-like papardelle as well as the crimped garganelli. The latter, according to De Cecco, derives its name from the word "garganel," meaning chicken's esophagus in a dialect of Emilia-Romagna. These pastas tend to have a bright yellow hue to them and yield a moister texture than traditional pasta, making them suitable for almost any sauce.

Italy Magazine notes that it is not uncommon to still witness "sfogline" — or women who make this rich pasta — working in the classic way in Emilia-Romagna. While the ratio of egg to flour may vary by region and depending upon whether the flour used is a hard or soft wheat, the local saying is "the egg will choose the quantity of flour it needs." It is also tradition for the color of egg pasta to be adapted by supplementing the basic dough with ingredients like spinach, saffron, mushrooms, pepper, and cocoa. Whichever supplement is chosen, this will determine the appropriate topping for the dish.

Pasta fresca

Fresh vs. dry pasta is an age-old debate that appears to still leave consumers perturbed. The Washington Post notes that the answer to which type of pasta to use isn't a matter of good vs. bad, but rather one of utility. Most fresh pasta available tends to be of the egg variety and can be found in the refrigerated section of the store. For this reason, its shelf life is shorter, dictating that it be used within a few days. Fresh pasta can be fragile, lending itself to silky, smooth sauces that coat the noodles gently. Additionally, fresh pasta has a much shorter cooking time — about 1 to 3 minutes — as opposed to 15 minutes or more for dried pasta.

Dried pasta, on the other hand, has a long shelf life, making it ideal for buying in bulk. It is also less fragile and therefore better suited to robust, chunky sauces, like a Bolognese. This is attributable to the fact that dried pasta develops a ridged surface — a by-product of extrusion — which holds onto sauces, per our sister site Tasting Table. The Washington Post goes on to state that you should always follow the instructions on a recipe as to which to choose — fresh or dry — as most recipes have been tested with one or the other in mind for the ultimate flavor and texture. If you opt to substitute fresh for dry, add less liquid to the recipe to accommodate for the fact that fresh pasta won't absorb as much moisture in the cooking process, which can make your sauce too soupy.

No-boil lasagna noodles

"No-boil" or "oven-ready" lasagna noodles have been around since the 1990s, according to the Los Angeles Times. While they are made of the same basic ingredients as conventional lasagna noodles, the no-boil noodles are par-boiled and then dehydrated, per HuffPost. This process reduces their cooking time and enables their application directly into a lasagna dish along with the other ingredients without the hassle or sticky mess of boiling lasagna noodles.

Because of the way in which the noodles are produced, they tend to take on a lot of moisture in the cooking process. This requires that more liquid be used in the lasagna and that the dish is covered with foil during baking to ensure that steam builds up during the cooking process. Doing so will allow the noodles to cook all the way through without drying out the lasagna. It is also important not to overlap the noodles as they tend to expand during the cooking process.

Additional words of caution expressed by HuffPost include that the lack of starch in no-boil noodles — a natural by-product of the par-boiling process — makes these noodles slick. This can influence the structural integrity of the final product, meaning it may be a hot mess to try and cut into perfect square pieces without the noodles and ingredients sloshing around. The no-boil noodles are also easy to overcook, which can further compromise the texture of the final product. All of these precautions aside — if used with care — no-boil lasagna noodles can make a great home-made lasagna.

Rigate vs. lisce

The terms "rigate" and "lisce" are often associated with the penne noodle shape. Per Paesana, the basic difference is that rigate or "ridged" noodles tend to hold onto sauce better than lisce or "smooth" noodles. But True Italian states that this is an oversimplification which may mislead consumers.

Penne lisce is produced in the artisanal way — meaning it is slow-dried — enabling sauces to be absorbed without the pasta crumbling. Penne rigate is a product of the mass-production of pasta and is quick-dried. The resulting noodle is inconsistent and difficult to cook to a perfect al dente texture without over or undercooking. The ridges are an adaptation to accommodate this unpredictability, allowing these commercially produced noodles to allow sauces to adhere to them more effectively, regardless of how perfectly al dente the cooked noodles are. While consumers like the ease and convenience of the commercially produced rigate noodles, chefs prefer the classic lisce noodle for its dependability and quality.

What is the meaning of pasta numbers?

Have you ever noticed that many commercially produced pasta boxes have a number on them? According to Home Cook World, the numbers don't have much consistency across brands. The numbering system for each brand of pasta serves as a classification and product identification catalog within the brand itself. If you look at spaghetti, for example, the standard size for Barilla is No.5, while for De Cecco it is No.12. Both claim some degree of authenticity — yet there isn't anything immediately indicative that either is somehow more or less legitimate in the canon of spaghetti history.

Home Cook World goes on to note that for Barilla in particular, their long pastas are numbered according to thickness — with the thinnest noodles, like Capellini No.1, having a lower number than the thicker noodles, like Linguine No.13. They also number their other shapes, but since these don't bear any similarity to one another, the numbers appear to be far more arbitrary. Ultimately, the numbers on pasta aren't all that useful from a consumer perspective unless you happen to be comparing which of Barilla's long pastas you want to use for a light tomato sauce vs. a thicker Alfredo sauce. Hint: the thicker the sauce, the higher the number you should use.

Non-GMO wheat

According to GMO Answers, GMO wheat pasta doesn't exist. In fact, wheat isn't one of the 10 genetically modified crops approved for cultivation in the United States. So why do some pasta manufacturers insist upon including the redundant label "GMO-free" on their packaging? Peel Back the Label sheds light on this clever marketing tactic. In an industry that is increasingly competitive, companies are seeking to create the illusion that their product is somehow superior to others. Because of the ongoing discussion regarding the safety of GMO products, this term instantly suggests that the pasta is safer and of higher quality.

And yet, per our sister site Health Digest, there is anecdotal evidence suggesting a difference between American-grown wheat and European-grown wheat. Many Americans who identify as having gluten intolerances note that while they cannot digest pasta manufactured in the U.S., they have no problem consuming and digesting pasta while traveling in Europe. This has piqued the curiosity of many as to what might be the culprit of this phenomenon. America produces predominantly hard wheat, which is higher in gluten, while Europe produces predominantly soft wheat, which is lower in gluten. Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest that the widespread use of the herbicide glyphosate on American wheat may be disrupting the microbiome of our gut, killing off good bacteria that contributes to healthy digestion.

So while there is a difference between American and European wheat — non-GMO isn't it.