The Complex And Surprising Origins Of Modern-Day Cream Cheese

The year was 1872. Maybe 1875. Could've been 1877. It was sometime in the 1870s; that much, historians are pretty sure of. Dairy farmer William Lawrence lived in Chester, New York, and he bought a Neufchâtel factory. A big city client — a fancy grocery store called Park and Tilford — requested a richer version of Neufchâtel (that they could sell at a higher price, of course). Lawrence added more cream and called it "cream cheese." In 1877, Lawrence created the first cream cheese brand: Neufchâtel and Cream Cheese. He was a dairy farmer and cheesemaker, not a brand manager.

Cream cheese was an immediate hit. By 1889, according to Rabbi and cream cheese historian Jeffrey A. Marx, cream cheese cost 30 cents per pound, seven cents more expensive than Parmesan (in today's money, seven cents is $2.32). Other farmers upstate started making cream cheese, creating competition. Lawrence pairs up with a cheese broker named Alvah Reynolds and it flies off the line so fast that Lawrence starts contracting with other dairies. Then he starts buying dairies, creating the Phenix Cheese Company. Philadelphia is known at this time as the premier place to get the best cheese, and Reynolds suggests Lawrence use it in the brand name for his cream cheese — one you may have heard before: Philadelphia Cream Cheese. Prices came down in 1920, making cream cheese affordable for more households. Phenix goes national. In 1928, Phenix merges with a younger but very successful company: Kraft.

What's the difference between Neufchâtel and cream cheese?

Cream cheese might be a relatively recent invention, but Neufchâtel sure isn't. The cheesy predecessor dates back to around 1035 C.E., originating in Neufchâtel-en-Bray, France. It's one of the country's oldest cheeses. It can be formed into any number of shapes, including squares, bricks, cylinders, and hearts. Unlike cream cheese, Neufchâtel features a bloomy rind, like Brie or Camembert cheese. It's grainier in texture than cream cheese and has a fat content between 23% and 45%.

Over time, the US Department of Agriculture created standards for what could and could not be sold as cream cheese. Cream cheese in the U.S. must have a fat content of at least 33%, a moisture content of 55%, and a pH balance between 4.5 and 4.9 — quite acidic. Modern-day cream cheese is firmed with lactic acid instead of rennet, like Neufchâtel and many other cheeses. This shortens its shelf life and actually makes for a difficult cheese to produce. It's often stabilized with carrageenan and carob-bean gum, which also help keep it together when baked compared to newer, natural cream cheeses that don't contain stabilizers. This is why you want to use a cream cheese brand like William Lawrence's Philadelphia for your cheesecake recipe.

A surprisingly difficult cheese

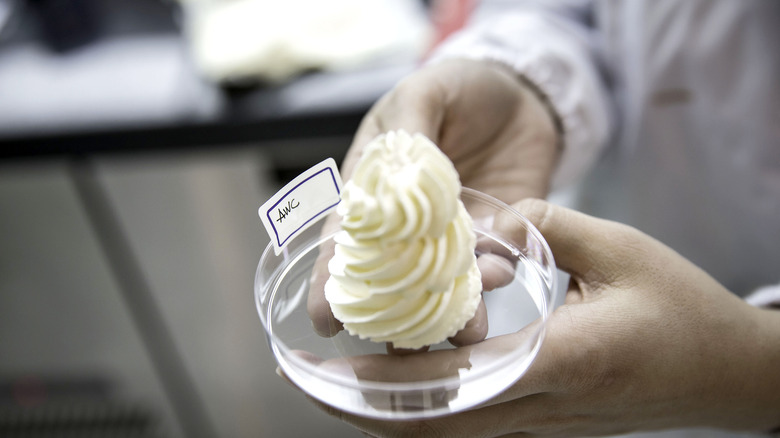

It's interesting that cream cheese is known to producers as a bit of a frustrating head-scratcher, since William Lawrence certainly wasn't a chemist. But Mercedes Brighenti, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (where else?), is determined to uncover the secrets of cream cheese at a molecular level. By understanding it more deeply, cheesemakers and scientists may be able to innovate even better cream cheese in ways that don't involve the vault of secret knowledge and recipes in Kraft's Chicago headquarters. Brighenti and her boss, John Lucey, get calls and packages from flummoxed manufacturers about cheese that smells like dirty socks, cardboard, or cough medicine, signs of bad bacteria, or of good bacteria gone bad.

Since cream cheese is coagulated with lactic acid formed by bacteria, not enzymes from rennet, it can be a little harder to get right over time. As the bacteria lower the pH, the proteins in milk stick together, and cheese is formed. If the bacteria keep going and more acid is created, though, the cream cheese re-liquifies. If a cheesemaker doesn't kill the bacteria at just the right moment, the cheese won't stay set. Flavor additives can further create issues for consistency (and sometimes explosiveness) as they introduce more molecular complexity. Lucey and Brighenti's continued research on the structure and behavior of cream cheese has contributed to cream cheese developments in flavors and textures (and a more exciting bagel experience than originated sometime in the late 1870's in Chester, New York).

Advances in cream cheese

As of 2021, with more than 15 years of research under her belt at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Mercedes Brighenti was still publishing papers on cream cheese. Most recently, Brighenti and John Lucey were looking at a complete recipe change. William Lawrence's recipe blended sweet cream and milk, but Brighenti's paper in the Journal of Dairy Science spotlighted whey cream. With smaller fat droplets and a different chemical composition, whey cream is the product of clarified cheese whey spun through a centrifuge, leaving small milkfat globules. In the search for more spreadable cream cheese, using whey cream — an "underutilized" ingredient in production — seems promising. The study found that higher percentages of whey cream in the cream cheese recipes did indeed create stickier, softer cream cheese. If you've ever dealt with the displeasure of ripping apart your bagel or bread slice as you try to spread cream cheese over it, this research is relevant to you. Manufacturers have produced whipped cream cheese as a more spreadable option, but this recipe revelation may create a spreadable cream cheese with the same luscious density as the regular stuff.

Plant-based, vegan cream cheese represents another new frontier in cream cheese metamorphosis. In 2022, Philadelphia entered the non-dairy market, the first time a top cream cheese brand ventured into the space. Eight months later, Philadelphia launched its first flavored non-dairy cream cheese. Even 150-ish years later, Lawrence's invention continues to "spread" in popularity thanks to fresh innovations.