13 Foods That Used To Be Popular But We Don't Eat Anymore

History has shaped food trends with oscillating periods of abundance and scarcity. In the 20th century alone, world wars, economic depression, and postwar reconstruction defined and redefined eating habits, making for a vast array of once-essential culinary exploits that today are distinctly things of the past. A greater nutritional awareness beyond mere diet fads has further contributed to the evolution of everyday dietary inclinations, rendering many previous culinary staples obsolete. With a culture currently trending towards fresh and local ingredients whenever possible, many canned and preserved foods — innovations for their time — are not only taken for granted, but no longer sought after, and the same goes for the dishes they once created.

Here is a list of dishes that were once widely consumed, many of which persist with a retro bias if they continue to be made, eaten, or enjoyed at all. That such meals could rise and fall within distinct cultural moments speaks to the evolving nature of taste, and the human impetus to make do with what's available, whether that be a little or a lot.

Ambrosia salad

Ambrosia salad first appeared as a very simple recipe in the late 1800s, making use of only three ingredients: layered orange slices, coconut, and sugar. Though many would declare the dish originated in the South, the early recipes for this fruit salad appeared widely in restaurants and cookbooks across the Midwest and East Coast, too. Its initial appeal may have been exoticism, as oranges and coconuts were expensive, tropical fruits that only wealthier classes could then afford.

In the following decades, the recipe incorporated additional fruits like pineapple and banana, and was topped with whipped cream. During the turn of the century, a marketing campaign introduced marshmallow whip as the dressing of choice, inching this salad even further into the realm of dessert. Perhaps due to the South's closer proximity to tropical climates, ambrosia salad had, by the 1930s, been deemed a traditional Southern holiday confection. This seems to be an association of agricultural cycles as much as Christmas tradition, as Florida oranges typically reached grocery shelves in December.

With canned fruits becoming staples during and after both World Wars, ambrosia salad reached its recognizable retro form with canned pineapple, maraschino cherries, and mandarin oranges, persisting into the mainstream with the buffet boom of the 1980s. Perhaps through the contemporary inclination to avoid salads dressed with preservatives, ambrosia salad is viewed today with more nostalgia than anticipation. Whether considered a salad or dessert, this dish maintains Southern associations largely because this is the only region where recipes persist.

Tuna casserole

The postwar proliferation of canned foods in the 1950s started a culinary phenomenon of quick and easy-to-prepare meals that could be made straight from the pantry. Tuna casserole, as Campbell's elegantly describes it, was the "original dump and bake." With many recipes calling simply for canned tuna, cream of mushroom soup, noodles, breadcrumbs, and peas, it's fairly quick to get this mixture in the oven. An easy, fortifying, relatively hands-off meal, it hasn't disappeared from the 21st century diet completely, but many factors may be contributing to its ever-receding popularity.

"A lot of millennials don't even own can openers," Andy Mecs, former Vice President of Marketing and Innovation at StarKist, told the Wall Street Journal as one possible reason why canned tuna might be less in demand. Though StarKist's invention of tuna in vacuum-sealed pouches has been a way of marketing this as an even more convenient ingredient, residual associations between tuna and high mercury levels may still be prompting many to use tuna in moderation. Though mercury concerns were largely due to environmental hazards in the 1970s, tuna got a further bad rep with the eventual understanding that tuna nets often ensnared dolphins in the process, forcing tuna brands to change their practices and provide the distinction of "dolphin safe" in order to keep customers consuming. While today's tuna is generally a safer product, lingering distrust as well as a cultural preference toward generally fresher ingredients have certainly inspired a decline in tuna-based dishes.

Pineapple upside-down cake

First surfacing on palates in the 1920s, this topsy-turvy dessert may initially have had more of a luxury association. Pineapple had only recently reached more mainstream status in the 20th century via the establishment of Jim Dole's Hawaiian Pineapple Company, which efficiently mass-produced canned pineapple, enabling more people to be able to access and afford this tropical ingredient. Dole was soon producing canned pineapple in quantities far greater than the present consumer demand and resorted to advertising strategies in hopes of increasing pineapple consumption. Revolutionary Pie explains that Dole sponsored a contest for the best pineapple-centric recipe, selecting a certain Mrs. Robert Davis's pineapple upside down cake as the winner. From there, the dessert took off, becoming a household favorite in the following decade.

Pineapple was a tropical take on a much older dessert phenomenon. "Upside down cakes" have been around since the Middle Ages, but Dole's advertising certainly helped the concept reach a wider pool of consumers. The dessert experienced a surge in popularity mid-century, perhaps due to the call for convenience cooking that prompted home cooks of the 1950s to reach for canned ingredients first. Today, the dish occasionally appears at social gatherings as a potluck dessert, but it does not share the widespread popularity of its retro resurgence. Whether the dessert itself has been a fad that rises and falls, the canned ingredients (and often the maraschino cherries that garnish it) have been unable to fully transcend a retro association.

Meatloaf

Though meatloaf-like predecessors were enjoyed as far back as the days of Ancient Rome, the dish was most popular in northern Europe for centuries; it was the German-descended Pennsylvania Dutch who devised a meatloaf prototype in the States. Their dish, known as scrapple, makes use of all the extraneous parts of meat left over from a butchering session, which then get ground, mixed with fillers, and pressed into loaf tins to be easily sliced and fried in pieces.

A few major events of the 20th century inspired meatloaf's mainstream popularity, since it was a humble but versatile dish that was adaptable in times of scarcity. With scant food sources during world wars and the Depression, Americans embraced the meatloaf as a simple but nourishing staple that could feed many on a low budget. The dish remained popular well into the 50s and 60s, when creative cooks embraced meatloaf's simplicity while experimenting with its versatility.

While meatloaf has by no means disappeared (and even occasionally finds its way into the realm of the gourmet with elaborate renditions incorporating all manner of spices and unusual flavorings), it is no longer a nationwide staple as it once was. Though non-meat meatloaves are nothing new — those maneuvering around war rations once made creative vegetarian versions with nuts and legumes — a growing prevalence of plant-based preferences may be a contributing factor to the traditional meatloaf's popular decline. While still wholesome and hearty, its heyday has been overshadowed by abundance replacing scarcity.

Fondue

The fondue phenomenon was an attempt by a cheese cartel — the Swiss Cheese Union – to market Swiss cheese beyond Swiss borders. Fondue had been around long before this post-WWI campaign to heighten a practical winter peasant dish, but by the 1930s, with the success of aggressive, targeted advertising, the cheese cartel elevated fondue to an elite status as Switzerland's national dish. This Swiss culinary compulsion reached similar popularity in the US a few decades later.

Though the fondue fad had a brief resurgence in the 1990s, its associations are largely still with the Disco Decade. The communal aspect that once made fondue so popular has since been replaced by the collective dining traditions of other cultures. In a time when many popular diet trends advise followers to cut out both bread and dairy (traditional fondue's two main staples), cheese fondue doesn't hold up against hot pot or shabu-shabu.

Chocolate fondue, on the other hand, isn't quite so démodé, but perhaps that speaks mostly to a timeless love of chocolate. An American take on dessertifying classic cheese fondue, the chocolate variant was also a mid-century innovation to keep up with the fondue trend, and has evolved to become somewhat of a special occasion treat (largely thanks to the chocolate fountain). Though both sweet and savory renditions of fondue are no longer common stateside, cheese fondue remains widespread in Switzerland. Despite the Swiss Cheese Union having long since disbanded, fondue is still the Swiss national dish.

Tapioca pudding

Derived from the cassava root, tapioca originated in South America. A processed ingredient, it is available in three common forms: seeds, flakes, and pearls. Though tapioca pearls have a different association in the 21st century with the present international boba craze, they were once widely used for a completely different sweet treat. According to the Oxford Companion to Food, "Pearl Tapioca, rather than the quicker cooking flake kind, is preferred for tapioca pudding..."

As a healthful starch, tapioca became popular in the 19th century and, according to John Ayto's An A to Z of Food & Drink, was valued for its "possession of that elusive quality of Victorians, digestibility." Considered nutrient-rich and easy to digest, it was often served to children, though its health associations may have been why it was not enjoyed as widely as it was available. The texture, for some, was also off-putting, as cooked tapioca pearls can take on a lumpy consistency. Tapioca pudding as a dessert took off at the end of the 19th century, when Boston's Susan Stavers achieved a creamier pudding sans lumps by grinding cassava in a coffee grinder. This textural shift was an instant success, and the grinding methodology turned into a lucrative business venture, The Minute Tapioca Company.

Though tapioca pudding is still available ready-to-eat in many grocery stores, the nutrient properties of its early iterations no longer hold up in pudding cups. Tapioca pudding's former popularity, it seems, has largely been replaced by other trending tapioca products.

Liver and onions

Liver and onions, for some, may invoke a visceral reaction with its name alone. With the origins of (and preferences for) the dish culminating in the UK, the pairing's stateside lack of popularity seems to be simply because Americans have not completely developed a taste for it.

Liver and onions come as a package deal — the onions, once cooked, contribute a slight sweetness that counteracts liver's somewhat metallic taste. Even slathered in sauce or stuffed into a sandwich, the strong, often bitter or gamey flavor of liver does not rank it among crowd pleasers. Negative associations may have just as much to do with bitter memories of being forced to eat it as with the potentially unsavory taste.

Liver and onions was previously widely available as a diner staple, but the dish has lost prevalence, perhaps in tandem with a dwindling diner culture. Even when seeking a diner meal, people simply don't stop in for a plate of liver and onions anymore. A cheaper cut of meat, liver doesn't conjure the same luxurious sentiments as choicer cuts of beef, and, though hearty, isn't regarded as a comfort food source of protein like the ubiquitous burger. But liver is full of many more nutrients, especially vitamin A, vitamin B, copper, iron, and selenium, which has earned liver the distinction of being an underrated superfood. Even though liver contains significantly more vitamins than spinach or kale, it appears to be one superfood that has not caught on.

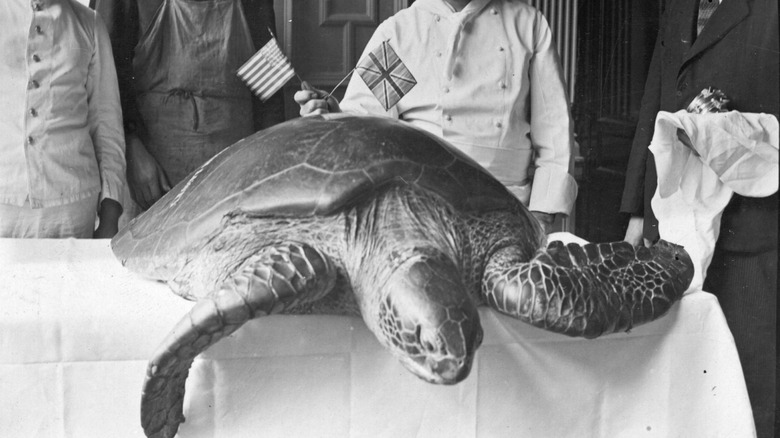

Turtle soup

Though it has English origins, turtle soup quickly became a popular dish in the American colonies, but was generally deemed a luxury due to the high price of turtle meat. So high was the demand for this delicacy (largely imported from the West Indies) that it put turtles at risk of extinction.

Rather than going out of style, turtle soup left the mainstream because there were not enough turtles to go around. The taste for turtle was largely due to the variety of flavors the meat provided; different parts of the animal resemble the flavors and textures of other meats, such as veal, goat, beef, and pork. The solution to keep up with demand was mock turtle soup, which became available in the mid-18th century. Recipes for this mock version settled on calf's head as the cut of meat that most closely resembled the texture and tastiness of turtle.

Mock turtle soup remained popular well into the 20th century. They even garnered a place on grocery shelves when Heinz and Campbell's endeavored to produce canned varieties; however, those were eventually discontinued. The original may have fallen from favor due to the time-consuming preparation required to properly prepare a calf's head; hours of toil couldn't compete with the midcentury penchant for convenient and pre-packaged meals. Since the 1950s, turtle soup has been a seldom-cooked dish in the States, but is still enjoyed as a delicacy in China, Singapore, and other countries in Southeast Asia.

Fruitcake

With humble beginnings in Ancient Rome, fruitcake's origins are practical, irrespective of where it stands on the popularity scale. Smithsonian Magazine reports that its original form was a mashed combination of barley, pomegranate seeds, nuts, and raisins, a portable food with a long shelf life — more or less an ancient power bar. This kind of daily sustenance evolved into more special occasion fare during the Middle Ages and beyond, and was favored by the Victorians who relished fruitcake's long shelf life due to its dense texture and the spirits infused within. Since fruit itself was a costly commodity at the time, fruitcake was always a dessert for special occasions.

Though fruitcake's reputation has been somewhat mysteriously besmirched, it does remain popular outside the United States, where it persists as a traditional British wedding cake and has long since become a Bengali culinary fixture for any occasion. However the derision started that prompted fruitcake to become widely despised in the States, hating fruitcake is today as much a holiday tradition as the dessert itself. This has prevented many, on principle, from ever wanting to try fruitcake, with the assumption that it must be awful. Consequently, fruitcake's decline in popularity may have nothing to do with its merits as a dessert. As chef Carla Hall summarized for Forbes, "I guess it is one of those things that is psychological. It inherently isn't bad but we all have a stigma associated with it."

TV dinners

Dinnertime in the 1950s was replaced with a new pastime integrated (and quickly integral) to daily life. Television had been a rare sight in American homes by the time the decade rolled around, but Smithsonian Magazine reports that by 1955, more than 64% of households had a TV set. The 50s was already an era of convenience cooking uniquely suited to the invention of the ultimate easy meal, which created the perfect demand for the antithesis of home-cooking. Hours saved from kitchen prep could be put towards watching television instead, making the TV dinner as much of a novelty back then as television itself.

Though a variety of pre-portioned heat-and-serve meals were available to the middle-class families that largely consumed them, this concept was initially a marketing scheme to re-package leftover Thanksgiving turkey. The result: a perennial trend towards a thriving frozen dinner industry.

TV dinners in their original form required half an hour or so in the oven, a convenience further expounded upon with the invention of microwaveable meals in the 1980s. But rather than heightening the dish's popularity, it seems too extreme a convenience has caused many to become suspicious of such instant cuisine's capability as a true meal. In terms of convenience and enforced portion control, TV dinners can't be beat. But a contemporary understanding that nutritional value is often lacking from pre-prepared frozen meals — which are usually highly processed and full of sodium — has many deferring to other meal options instead.

Sloppy Joes

The sloppy Joe's origins are somewhat hazy, but some lore suggests it may have ties to Ernest Hemingway. Having spent many years in Cuba, the American writer might be the link that imported the recipe for ropa vieja (featuring shredded beef stewed with tomatoes) from a Havana bar to his favorite watering hole in Key West. This Florida bar, either by coincidence or design, was named Sloppy Joe's.

The sandwich itself is a simple concoction: a hamburger bun filled with ground beef cooked in seasonings and a sauce of choice, anything from ketchup to Worcestershire. No matter the exact origin of this humble fare, sloppy Joes became a popular household staple during the 1930s, when stretching meals was the fashion and necessity of the times. Since the '30s, though, this sandwich hasn't appeared nearly as often as it once did, and the reason may be embedded in the name.

"I think that unlike a burger, wrap, or burrito they are not as mobile," chef Paul Blackerby of the Hyatt Regency Monterey told Monterey County Weekly in speculating on the sloppy Joe's decline in desirability. "I just wonder what the bun would be like after sitting for more than ten minutes." Certainly the sloppy Joe is not as portable as other hot sandwiches, which doesn't bode well in a continued culture of convenience fast food and drive-thrus.

Cherries jubilee

Cherries jubilee is a dessert of Victorian origin, purportedly created in honor of Queen Victoria herself — whose favorite fruit was well-known to be cherries — in celebration of her diamond jubilee. The creator to whom this dish is attributed is the esteemed French chef Auguste Escoffier, and while the final outcome may appear to be nothing more complex than a cherry compote, it is the manner in which it is prepared that makes simple ingredients into a unique show stopper.

For the original recipe, the cherries got poached into a syrup, added to a spoonful of Kirsch, a cherry brandy, which was set alight just before serving. The blue flames that engulf the dessert make the whole more sophisticated than the sum of its parts, and the original was served on its own. But the recipe quickly adapted into more of a jazzy topping for vanilla ice cream, and experienced a renaissance in the mid-20th century. Into the 1950s, cherries jubilee was featured in many cookbooks, becoming a trendy dish to serve as dinner parties' pièce de résistance. As Martha Deane says in her 1954 cookbook "Cooking for Compliments": "Few things are easier than this dessert with a cosmopolitan air." Since this new height in the 50s, however, the then trendy dessert has yet to experience another resurgence.

Gelatin salads

Gelatin, that textural oddity that comes from boiling animal skin and bones, was once a status symbol, but this was largely because the process of making it was quite labor-intensive. Though today gelatin persists as a predominantly sweet treat largely associated with Jell-O, an individual brand, there was a time when gelatin dishes were meant to be entirely savory.

Gelatin salads reached peak popularity in the form of aspic, which particularly appealed to the Victorian palate in the form of meals of meat encased in gelatin. Aspics could be works of art, particularly from afar, though up close they might appear a bit unsavory to the contemporary eye.

Eventually, due to a scarcity of resources during the 20th century's numerous wars and subsequent economic hardships, gelatin escaped its elite origins to become a means of pure sustenance. Congealed salads were a way to stretch meals and reduce waste; leftovers could simply be served in a new form surrounded by a gelatinous casing. Though gelatin-based dishes fit the postwar inclination towards neatness and efficiency that defined many culinary habits of the 1950s, there is little evidence to suggest even then that gelatin salads were actually enjoyed by those who had to eat them. It may go without saying, then, that this meal trend, despite a fairly lengthy history, was never meant to last.