The History Of Margarine Goes All The Way Back To Napoleon

The battle between butter and margarine is a fierce one. While it may seem to be a modern struggle, the history of margarine goes all the way back to the reign of Napoleon III in mid-19th century France. France is perhaps best known for their love of butter in cooking. Surprisingly, margarine was created in France to act as an alternative to butter and since has become one of butter's big competitors. Margarine is a combination of oils and water. Originally margarine was designed to mimic butter. At room temperature, it is a soft solid but can be melted into a liquid. That said, of course, there is also liquid margarine available now, which brings a buttery taste without the need to melt butter.

There are a number of reasons margarine might be used, and throughout history, as margarine's popularity has waxed and waned, these reasons have varied. At times popularity has been driven by availability, rationing, or as a way to avoid dairy, though it should be noted that not all margarine is dairy free. The first margarine ever invented, in fact, was still made using milk.

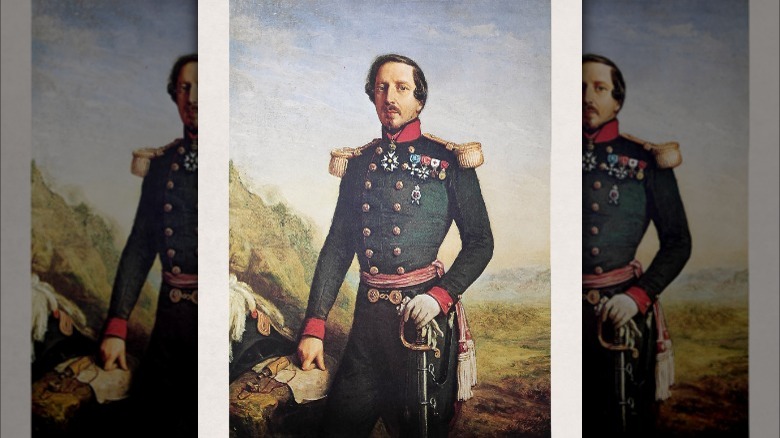

Napoleon III's France

We can thank the French emperor Napoleon III for the invention of margarine. Napoleon III was the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, who became first the president of France and then the emperor. As a ruler, Napoleon III was incredibly effective, and France was doing pretty well. However, not all was perfect. Due to a combination of citizens moving to the city and a need to feed large numbers of citizens and armies, butter became scarce and expensive.

But Napoleon III had an idea. In 1869 he created a contest and offered a prize to whoever could create the best alternative to butter. The winner of the contest was Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, a renowned French chemist who also created the first treatment for syphilis.

Mege had studied dairy and fats for years and was able to create a substance made from beef fat and milk that mimicked butter effectively and won him the prize. The name margarine came from Michel Chevreul, a contemporary and influencer of Mege, who created animal fat balls he named "marganon," which is the Greek word for pearl, which in turn led Mege to call his invention margarine.

Invention of hydrogenated oils

Margarine continued to be produced for years, and Mege was granted a patent for his invention in France, England, and later in the United States. Things were going pretty well and eventually, Mège-Mouriès sold the patent to the Dutch butter company, Jurgens & Co. Through the company's access and network, the popularity of margarine began to spread. That is, until another shortage hit, this time beef tallow, the fat used to make margarine.

This caused a problem for margarine, which once again needed to pivot in order to keep up production. The next big break came in 1902 when Wilhelm Normann invented the process to hydrogenate oil. Hydrogenated oil was simply oil that had been changed to be hard at room temperature. By 1909 hydrogenated oils were hitting the market on a large scale. 1911 saw the first market introduction of shortening in the form of Crisco, a fully hydrogenated oil product. Hydrogenated fat became more and more popular through the early 20th century, and by the 60s, hydrogenated vegetable fat was overtaking animal fat. Not only did the invention of hydrogenated oils mean margarine could now be made without beef products, but it also allowed the butter substitute to remain spreadable, even when kept cold.

Popularity in the Jewish community

Now that margarine could be made without milk or dairy, it opened up a whole new market that had previously been untouched: the Jewish community. Those who adhere to Jewish food laws of keeping kosher cannot mix meat and milk. Since the original version of margarine was both meat and dairy, it was not accessible to those who kept kosher.

Once hydrogenated vegetable oils came onto the market, though, things changed. Crisco made waves when it first became available. It was so important because it was not just kosher, it was kosher parve, meaning it could be used in both milk and meat dishes. Crisco also received kosher seals stating its kosher certification. A document released in 1914 called "The Story of Crisco" explains that New York-based Rabbi Margolies declared that the Jewish community had waited 4,000 years for Crisco. While not all margarine is kosher parve, this opened up a world of butter-tasting spreads and allowed kosher-certified brands such as Fleichmann's to flourish.

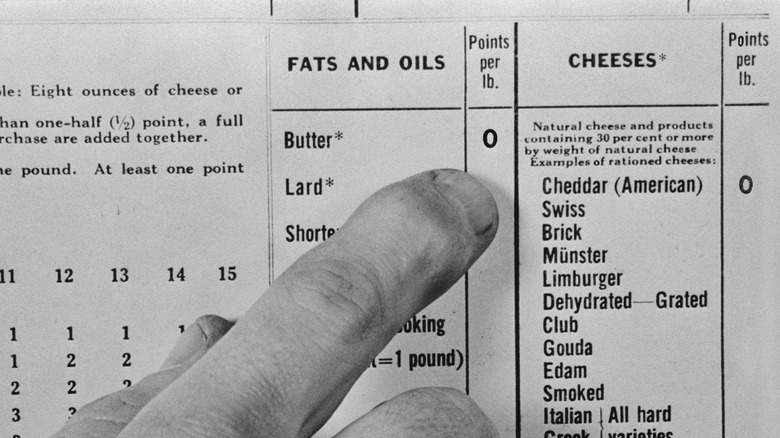

Rise during World War II

Margarine saw another boost thanks to another butter shortage, this time several decades after its invention. During World War II, mass shortages, as well as rationing, caused a rise in the use of margarine. However, butter did not want to go down too easily.

Butter lobbyists had spent years getting legislation passed that made making margarine more difficult and expensive. This included adding taxes to margarine and requiring producers to get special licensing just to make it. However, this heavy legislation could not keep people away from the stuff when times got tough. Sales began to rise, and suddenly the politics of butter versus margarine began to shift.

During her time as first lady, between 1933 and 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt attempted to take on the butter industry and provide tax breaks for margarine. Ultimately this was unsuccessful, but the tides of public opinion were already changing, and in 1959 Roosevelt appeared in a commercial praising margarine.

Evolution of taste and appearance

The taste and appearance of margarine have changed greatly over time, but in more ways than people may expect. We have already discussed how the first margarine was made using milk and beef tallow. From there, both beef and dairy began to be removed from the equation. The first big change occurred in the late 19th century when Jurgens bought the patent for margarine. They created a non-dairy version; however, this still used beef fat. The beef fat was removed with the creation of hydrogenated oils. Improvements came in the form of texture, as spreadable margarine came to the table. The biggest change, though, arguably came in color.

Early forms of margarine, especially those that used oil as a base, were white. So naturally, colors were added to give them more of a butter-like look. However, butter manufacturers were not happy about this and successfully lobbied in many states to enact so called "pink laws," which required margarine to be colored pink, not yellow. These laws were eventually repealed.

During World War II, when there were still regulations around coloring margarine, margarine was sold in white bricks. However, they came with a capsule of yellow food dye that had to be worked into margarine so people could tint the margarine a butter-like yellow at home. Since then, laws have been lifted, and margarine can now be sold in colored forms.

Entrance of healthy margarine

Margarine was coming along swimmingly in the public view. Once it had become a regular feature on tables and people were beginning to think of margarine as a real contender for the position formerly dominated by butter, marketing companies wanted to know how they could make it better and stake out their own claim in the buttery spread market.

The first significant change came in 1964 when a low-calorie version of margarine went on the market. At the time, the FDA was not too pleased about it and argued that the product did not count as a table-spread product. However, they lost the case.

With the introduction of low-calorie and low-fat margarine, new regulations in regard to naming were put in place. Diet margarine became its own category. Diet margarine had to contain half the fat of butter at 40%, as well as half the calories.

As more of these spreads came on the market, their popularity began to grow. As a result, sales went from 5% of the United States market in the 1970s to over 70% by the 1990s.

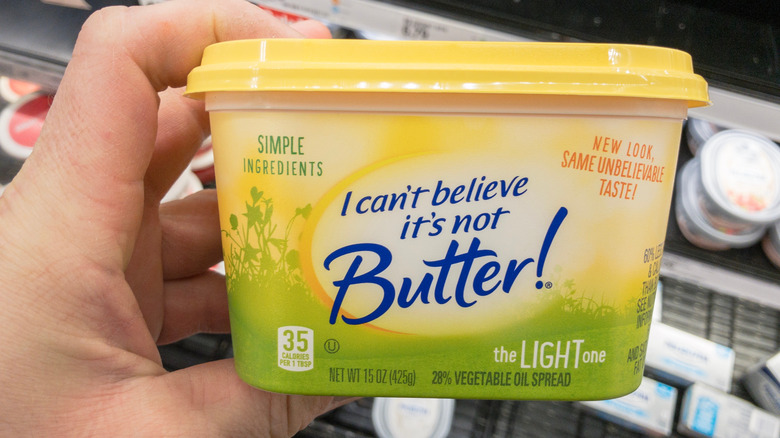

Butter vs margarine vs. spreads

While often the terms margarine and spread are used interchangeably, there is actually a legal difference between them.

Margarine, by definition in the United States, has to contain 80% fat, just like butter. The invention of low-calorie and low-fat butter led to diet margarine, which had its own restrictions. But in 1975, a low-fat buttery spread came on the market that met neither the criteria for margarine nor diet margarine. The product was 60% fat, which led it to not be allowed to label itself as either and was considered a table spread. It should be noted that due to their low fat content, table spreads and low-fat margarine are not ideal for baking.

The 1980s saw a rise in combinations of butter and margarine. The blends were an attempt to add more butter flavor while harnessing the benefits of margarine, such as spreadability and perceived health improvements.

The anti-butter movement

Part of the staggering increase in margarine and table spread consumption was due to a combination of politically charged dietary recommendations and clever marketing by the producers. It was clear from the get-go of diet margarine that producers were trying to capture a certain subset of the market concerned with what they considered health. This came to a head in the 1980s when the United States Department of Agriculture released dietary guidelines telling people to reduce fat and cholesterol in their diets. This came from the idea that fat and cholesterol in food were causing heart disease, a big problem.

Marketers seized on that and started promoting the spreads more. Butter is only made of a few simple ingredients, and at its lowest fat is 80%, so suddenly, the war on butter was one. Every time some new health concern came out, the industry adapted. This included eliminating trans fats from hydrogenated oils and other ingredients to keep up with trends.

The end problem was that, as it turns out, fat and cholesterol were not the problem. As Time notes, despite decreasing these in the diet, heart disease did not improve but the sales of margarine did.

Plant-based movement

Now we are back to accepting butter as a part of a regular diet, so the margarine makers needed a new angle. One particular diet trend has become more common over the years: vegetarianism or plant-based eating. This is done for a number of reasons, from environmental, to ethical, to simply not being able to digest dairy well. Whatever the reason, plant-based foods have grown in their share of the food market.

Plant-based butter sales grew 15% from just 2017-2019. The industry is now worth nearly $200 million. Plant-based butter can be made from any number of ingredients, including plant and seed oils, but they cannot contain any dairy or meat. This a callback to the invention of Crisco, though today's plant-based butter may taste better.

Not all margarine is plant-based butter. There are still plenty of margarines on the market that contain dairy ingredients. It is impossible to deny, though, that margarine has gone through some significant changes since Napoleon III first requested an alternative to butter, and consumers appreciate the results.