Wisconsin Cheese 101: How Cheese Is Made

Cheese 101: Milk

It should not come as no surprise that the best cheese starts with the best milk available. The top cheesemakers pride themselves on the quality and freshness of their milk. Chalet Cheese Cooperative gets all their milk from the 21 family-owned dairy farms in the co-op, none of which are more that 20 miles away. Crave Brothers takes it one step further with its farmstead cheese by raising its own grain to feed to its own herd of cows. The cows are milked and the milk is pumped directly from their dairy farm to their cheesemaking plant across the street — it doesn't get fresher than that.

Cheese 101: Bacteria

Unless the cheese being made is a raw milk cheese, the fresh milk is pasteurized. The milk is heated to 161 degrees Fahrenheit for 15 seconds to kill any harmful pathogens and bacteria to make it safe for consumption. However, the problem with pasteurization is that is also kills the helpful bacteria that give cheese its flavor and texture. Once the milk is pasteurized, the cheesemaker adds a starter culture of bacteria or enzymes, which covert lactose to lactic acid, acidifying the milk and starting the process of breaking down the proteins in the milk.

Cheese 101: Rennet

After the starter culture is added, another enzyme called rennet is added to the milk. Rennet is an enzyme that is used to destabilize the proteins in milk; it coagulates the milk so that is forms a gel-like mass. From this point, the clotted milk could become yogurt, soft cheeses like cream cheese and cottage cheese, or aged cheese. The steps that follow turn the clotted milk into aged cheese.

Cheese 101: Cutting

Once the cheesemaker determines the milk has clotted enough, it is time to cut the gel into smaller pieces. Large knives are run through the gel, which starts the process of separating the curds (which are the cheese solids) from the whey (the liquid). Once the clot is cut, the curds start to expel the whey. The size of the cubes that the clot is cut into determine the kind of cheese that is being made; larger curds yield softer cheeses because they retain more water, and smaller curds become harder cheeses because they have less moisture.

Cheese 101: Cooking

Curds are cooked to expel the whey. As with the way they are cut, the temperature and amount of cooking time are specific to the type of cheese being made; a higher temperature and longer cooking time expels more moisture and results in a harder cheese. The curds and whey are cooked and stirred until the right temperature and firmness of the curds are achieved. It's at this stage that fresh cheese curds, or "squeekers," are ready to be eaten.

Cheese 101: Pressing

Once the curds are ready, they are pressed into forms that will help determine the cheese's shape. Weight is placed on top to squeeze out additional whey, and the curds start to form into a single solid mass that will become cheese. The way they are handled is particular to the cheese they will become. Joseph Widmer of Widmer's Cheese Cellars still uses the bricks his grandfather bought in 1922 to press the whey out of the curds.

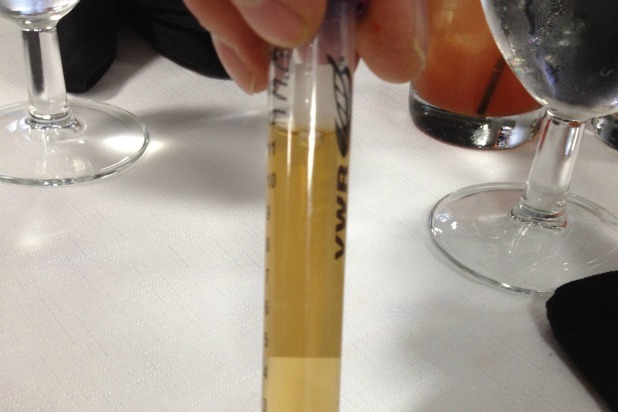

Cheese 101: Salting

Cheese curds are salted in one of two ways, direct salting and brine salting, and each cheesemaker has a slightly different method. In direct salting, the curds are covered in dry salt. At Chalet Cheese Cooperative, the curds for Limburger are dry salted and left to sit for a day. For brine salting, curds are submerged in a salt bath. Widmer's Cheese Cellars brine salts its German Brick cheese for 11 hours in a salt solution that is 90 percent water and 10 percent salt. Once the curds have been properly salted, they are rinsed.

Cheese 101: Forming

With the curds now salted and rinsed, they are pressed to form individual cheeses in their characteristic shapes. This process also releases additional whey and knits the curds. Blander cheeses that are higher in moisture, like mozzarella and queso blanco, are finished at this stage. They are not ripened or aged, and they have a short shelf life and must be sold and eaten quickly.

Cheese 101: Ripening

Ripening is what gives each cheese its distinctive flavor. There are four combinations of ripening. Cheeses like Cheddar and Parmesan are ripened internally, with the bacteria already in the cheese. Cheeses like Limburger, Gruyère,and Comtéare externally ripened with bacteria, where their surfaces are smeared with a wash that contains bacteria and then stacked on pine boards that contain the bacteria. Chalet Cheese Cooperative has been propagating its own strain of bacteria for its Limburger for 100 years.

Camembert and Brie are externally ripened with mold, and the "blues" like Roquefort and Stilton are internally ripened with mold. Blues are pierced with needles to let oxygen in to encourage mold growth, resulting in the "veins" visible in blue cheese.

Cheese 101: Aging

Aging a cheese does two things: It dries out the cheese, making it a harder cheese, and it gives more time for the bacteria or mold to do its work. This aging process gives cheeses like sharp Cheddar and Parmesan more distinct flavors. The finest batches of cheese are picked for the longest aging, typically 18 months or longer.