Tales Of The Cocktail 2011: More Than Alcohol

From creating signature sodas to taking a chainsaw to ice, seminars at the 2011 Tales of the Cocktail conference in New Orleans touched on a variety of topics to give beverage programs an innovative upper hand. The professional series of seminars geared towards those who work in the foodservice industry provided insights for operators and beverage program managers who want to push their beverage program.

The following are highlights from some of the seminars:

How to build a cutting-edge ice program

Chad Solomon and Christy Solomon, Cuffs & Buttons Cocktail Catering & Consulting

Joseph Schwartz, Little Branch

Richard Boccato, Dutch Kills, Weather Up Tribeca, and Hundredweight

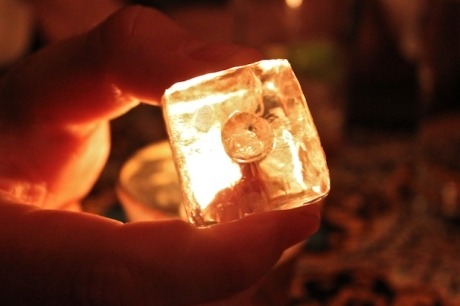

Moderated by Chad Solomon and Christy Pope, this seminar explained how to develop an ice program. Panelists Joseph Schwartz and Richard Boccato lent their expertise, while all four speakers drew on their experiences working with Sasha Petraske of Milk & Honey bar empire fame. They reveal what they learned about ice, and how they adapted and developed ice programs in their other ventures.

Why use 'good' ice? Ice does matter, especially when it comes to shaking, the panelists said. A solid piece of ice will remain whole for a longer time in a shaker. When Schwartz teaches his bartenders how to shake, he instructs them to "hit the top and bottom of the can" with the ice. A larger piece of ice can take such abuse without breaking apart. It also has a larger surface area, which means a slower melt rate. Since it won't break apart or melt as fast in a shaker, it allows the bartender to chill the ice for longer and aerate the drink without excessively diluting it. It also preserves the drink for a longer time in the glass before turning into what Schwartz called a "watery mess."

While good ice is isn't so much about making a drink colder, Boccato added, "It really does maintain the optimal temperature."

"Good ice can help create consistent quality, even if different bartenders are shaking," Schwartz said. "Let's not forget, it looks sexy."

Ice programs are adaptable. Mold your ice program around your resources, the panelists said. When Petraske of Milk & Honey wanted bigger ice cubes, staff used plastic hotel pans to freeze a block of ice that could be cracked and cut by hand.

When Boccato created an ice program for Dutch Kills, the neighborhood's water quality gave his ice an undesirable yellow tinge. He tapped an outside source to get block ice. When the first supplier's ice didn't come up to snuff, he remembered a local ice sculpture studio, which requires high-quality ice. Boccato developed a relationship with the artists who worked with him on idea sketches and glassware for new ways to cut ice.

Think of it as an investment. Whether time or money, a cutting-edge ice program needs investment. For example, a block ice maker or a blast freezer are just some ways to create ice, but can set an operator back several thousand dollars.

But even the most expensive equipment won't carry an entire ice program on its shoulders unless the staff gets involved. At Little Branch, Schwartz regularly arrived two hours before shift to work on the ice.

"In terms of trying to figure out labor cost, at Little Branch, two hours is unmolding all cubes, cutting what you have to cut, refilling all molds... it's part of a full open of a bar," Schwartz said.

Know when to spend less. For certain aspects of carving or cracking ice, Boccato used tools that mostly came down to old-fashioned elbow grease. Rather than use a specialty saw for carving ice, he chose a moderately priced chainsaw available at most big-box hardware stores. Chisels with sharpened edges can help score block ice and cut pieces. A cheap clothes iron can create smooth surfaces, shape ice or repair seams. And silicone ice molds can make cubes of varying shapes if you lack the resources to acquire large block ice to chisel. However, Schwartz cautioned that ice made in silicone molds should be removed immediately and placed in a different container, or the ice will take on a slight flavor if left in the mold too long.

Click here for more from NRN.com.

Creating an in-house soda program

Andrew Nicholls, Door 74, Vesper, Amsterdam

Darcy O'Neil, author and bartender

Attention to detail — seen most in cocktail programs as bartenders source and create their own recipes with bitters or infused alcohols — can also be applied to soda. In-house soda programs can give the bar more control in adding flavors and aromas to make drinks pop. And after all, soda is a key ingredient in classic cocktails, such as ginger beer in a Dark and Stormy or a simple tonic used in gin and tonic.

"[It's] an opportunity to create something unique and cater to the guests," O'Neill said. "Guests really appreciate it. It takes a bit of fine-tuning, but you can tailor a soda to a very specific product. You can create a balance or what you want to extract from a particular spirit."

Get the basics right. Carbonated water is the base for in-house soda programs. The basic anatomy of soda is water, carbonation, and salt. But it is not just a simple formula, the panelists note. Many factors exist in combining just these three ingredients. Choose distilled water, since it reduces contaminants that can add unwanted flavors to soda, the experts said. If only tap water is available, filter it.

Salt enhances flavor. That's why mineral water is served with meals, O'Neill said. "You can do the same thing with flat water as well and you can do a flat mineral water program."

There are many types of salts, and not just the difference between Fleur de Sel or Himalayan salt, but on a molecular level. Different salts cause different reactions or impart different characteristics, such as bitterness.

How to carbonate. For soda siphons, use the coldest water possible, the group said. The lower the temperature, the more carbonation. If using a nitrogen cartridge siphon to carbonate drinks, make sure to remove as much air as possible with a vacuum. One way is by boiling, then allowing the liquid to cool inside the siphon, they added.

More than a flavor. A soda's smell is also important, Nicholls said. Besides sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, aromas provide the rest of the tasting experience. Soda's fizz also helps disperse aromas.

An easy and inexpensive way to add aroma is with essential oils, since it only requires a few drops to make a difference, Nicholls said.

"When making soda with essential oils, all you do is smell it, but once sugar, salts or bitters are added, it changes very quickly, a wow moment," Nicholls said. "So you can't just mix essential oils and smell them and think that's it. At least add to simple syrup to taste before you drink."

Click here for more from NRN.com.

The Menu

Angus Winchester, on-premise consultant and profit enhancement and bar training expert

Sean Finter, CEO of Barmetrix

A bar's physical menu can help increase profits and market the establishment.

Most cocktail menus are born to fail for three common reasons, said Sean Finter of Barmetrix. The reasoning for what gets on the menu starts in reverse, there is either a lack of or confusion in the purpose of the beverage program, or cocktail choices are built around individuals.

For example, operators tend to create a cocktail list because they see cocktails as hot sellers, so the menu becomes an afterthought.

Most importantly, the menu needs to take into account the capabilities of the entire staff.

"The top 20 percent of the bar team builds a menu around the capabilities of that 20 percent, but they should be building the menu around the bottom 20 percent," Finter said. A cocktail menu is not an opportunity for staff or operators to show off what they aspire to be, but a reflection of what the bar does best. It should also convey the bar's mission statement, giving guests an impression of what the bar or restaurant thinks is important and the face it presents to guests.

Using the menu. A menu outside the bar can help draw guests in, even for a space that doesn't have a ground floor storefront. It can entice or inform guests before they even set foot in a location. Menus should also be available online, whether posted on a website or on other sharing sites. This also means that a menu needs to look good digitally as well as on paper, the panelists said.

It's how you say it (and how you show it). Evaluate critically the words or images on your menu. Pictures can create false expectations for customers, Winchester cautioned, so unless you can guarantee that the drink will be made the same way every time, photos can harm more than help. Instead, help guests visualize a drink with pictograms or simple line art of glassware next to the menu item.

Know, too, that a list of ingredients doesn't always convey what a drink will taste like, especially if the drink includes ingredients most guests aren't familiar with, the panelist said. Lengthy descriptions also create bulky menus that don't necessarily convey meaning to the guest.

Finter and Angus agreed that even with tablet technology, a bar shouldn't expect technology to make the sale for them. At one establishment, Finter was presented with a tablet menu, but when the server was asked to explain the menu and drink suggestions, she had to pick up the tablet and scroll through the menu because she did not know what was offered.

"Bars are supposed to be sociable places," Winchester said. "[Technology] is there to assist making a sale, not to make a sale."

—Sonya Moore