Menu Of The Week: Saratoga Springs' Congress Hall, 1856

Every week, we tap into the deep recesses of the New York Public Library's vast archive of old menus to take a look at the history of dining out. Click here for more Menus of the Week.

In 1856, Saratoga Springs, N.Y., wasn't yet known for its racetrack, which wouldn't open until seven years later. It was still a resort town for the wealthy, however, thanks to a feature that its name makes obvious: natural springs. These mineral springs attracted settlers even during colonial times, and in the early 1800s, especially after the Saratoga and Schenectady Railroad connected the town to the Eastern Seaboard's major cities, luxurious hotels began to sprout up left and right.

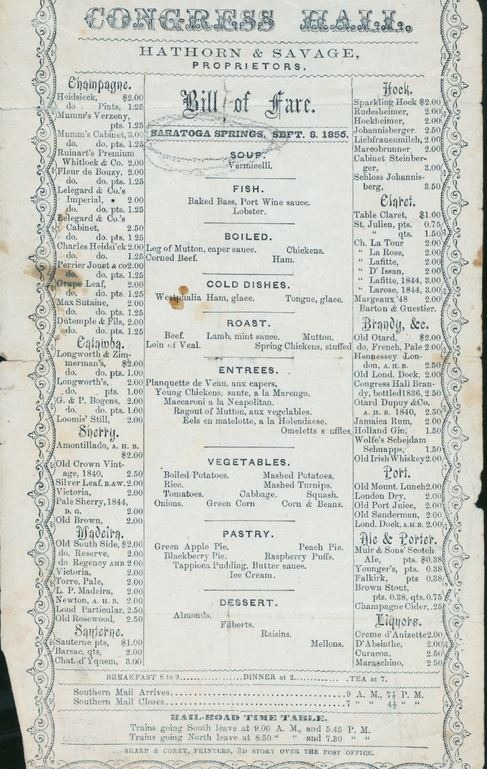

Congress Hall, with its sturdy mansard roof and stately arcade, was one of those hotels that catered to well-heeled visitors who were "taking the cure" at Saratoga. On Sept. 8, 1856, the bill of fare (which we tracked down via the New York Public Library's archive) featured a smallish but ornate assortment of what must have been the finest cuisine of the day; a good example of what the hoi polloi was eating in the years leading up to the Civil War. There was vermicelli soup to start, and baked bass with a port wine sauce lobster in the seafood department. Lots of old menus have a "boiled" section, even though that sounds rather unappealing today, and this one included leg of mutton, ham, corned beef, or chickens (love the fact that chickens is plural). Cold dishes included glazed Westphalia ham or tongue, and there was roast mutton, beef, veal, lamb, or stuffed spring chickens (again with the plural chickens).

Once we get to the Entrées section things get a little more complicated (and French, like all the fine menus of the day), with planquette de veau with capers (that actually should have been spelled "blanquette," a classic white stew); sautéed chicken with sauce à la Marengo (garlic, oil, fried eggs, and crayfish); Macaroni à la Neapolitan, which, believe it or not, was one of the first dishes to combine pasta and tomatoes; mutton ragù; and eels en matelotte, a rich stew made with wine and stock.

There was also a fairly standard assortment of vegetables, as well as a handful of pastries (I bet that blackberry pie was mighty tasty). Interestingly enough, the "dessert" section offers only almonds, filberts (hazelnuts), raisins, and "mellons," which is probably just sliced melon. Just goes to show how the definition of "dessert" has changed over the years. The definition of "dinner" has also changed over the years, apparently; it was served here at 2 p.m., with "tea" served at 7 p.m.

For those interested in the history of booze, this menu is also a goldmine. There's a vast array of champagne, catawba (the most widely-planted grape in America at the time), sherry, madeira, sauterne, hock (German white wine), claret, "Brandy, &c." (which also looped in gin, rum, schnapps, and whiskey), port, ale, and porter (not beer, notice), and liquors. That $3 Mumm's Cabinet champagne, when adjusted for inflation, would cost about $75 today, and the $8.50 Schloss Johannisberg cost the equivalent of $215. If you just wanted a pint of brown stout, however, it would have cost you the equivalent of about 10 bucks. No wonder this town was a destination for only the wealthy!

Congress Hall was torn down in the late 1800s to make way for the Frederick Law Olmstead-designed Congress Park, but it lives on today through a menu from September 1856, when mail arrived at 9 a.m. and "7 ½ p.m." and trains to all points south left and 9 a.m. and 7:45 p.m.