11 Fast Food Mascots Who Completely Disappeared

One would think that fast food restaurants wouldn't need to resort to aggressive marketing and sophisticated brand identification tactics — their products kind of sell themselves. Burgers, fries, chicken, soda, milkshakes, and other fast food favorites are so full of carbs, sugar, fat, and salt that they're populist and crowd-pleasing and enjoyed on some level by virtually everyone.

Children in particular like that style of fare because by and large they don't have tastes developed much beyond what's on offer at the average fast food place. And yet the most famous, notable, enduring, and effective forms of fast food advertising and marketing are the kinds directed at children, with campaigns built around smiling characters. Whether it's a guy in a suit, a cartoon, or something else, American fast food companies have a long history of using mascots to pitch their wares. Some are successful and last for a really long time — like Ronald McDonald, for example — while others flame out or get crumpled up into the trash can of history. Here are some once prominent fast food mascots that have disappeared from the public eye.

The Noid for Domino's

In order to differentiate itself from competitors in the explosive fast pizza industry, Domino's hired advertising agency Group 243 in 1986 to create a campaign built around a mascot, according to Fast Company. The agency's creation was unlike other advertising characters in that he didn't breathlessly promote the product but sought to destroy it. That's the Noid, a big-eyed, bunny-eared, spandex-wearing gibberish-speaking troll (brought to life by Will Vinton Studios, pioneers of Claymation and creators of the California Raisins). Noid's mission: To create chaos and make life miserable for Domino's drivers and customers, concocting and executing schemes to stop pizzas from getting delivered on time. Domino's ran TV commercials urging customers to "Avoid the Noid," and ensuring they were doing everything in their power to thwart the goblin's actions. The anti-hero became extremely popular, starring in a couple of video games and appearing on a line of merchandise.

According to Priceonomics, Domino's quickly ended the entire Noid campaign following an incident involving a mentally ill man. In 1989, a 22-year-old diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic named Kenneth Lamar Noid held two employees of an Atlanta Domino's outlet hostage for five hours, demanding pizzas, cash, and a getaway car. The hostages escaped, and police apprehended Noid, who claimed he did what he did because he thought the Noid ads from Domino's were personal attacks.

The Noid briefly reappeared in 2011 for his 25th anniversary, per Priceonomics, and again in 2021 with a video about Domino's self-driving delivery efforts.

The Burger King Kids Club

According to The New York Times, Burger King essentially gave up on the idea of marketing to children in the 1980s — believing that McDonald's had completely captured that demographic with its Happy Meals (kid-sized portions with a free toy) and immensely popular Ronald McDonald and McDonaldland characters. In 1990, Burger King, frustrated with missing out on that lucrative business, ramped up its kid-centered marketing, offering VHS copies of "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" episodes for sale at its store and launching a concept and character roster both known as the Burger King Kids Club.

Advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi developed the program, centered around TV commercials that were technically advanced for the time, combining live action, animation, and special effects that promoted Burger King's kids' meals via the endorsement of seven characters. According to RetroJunk, the cartoon kids included techno wizard Kid Vid, genius I/Q, cool guy Jaws, photographer Snaps, athlete Boomer, and wheelchair-racing enthusiast Wheels. All those animated figures appeared on Burger King kids' meal packaging as well as in a subscription-based newsletter children received in the mail.

At the end of the decade, Burger King switched tactics. After a 10-year run, the Kids Club disbanded, and BK renamed its Kids Club Meals the Big Kids Meal.

The Arby's Oven Mitt

By 2003, according to The New York Times, an attempt by roast beef sandwich chain Arby's to brand itself as a more sophisticated, adult-targeted fast food place — built around sensuous paeans to meat in ads featuring the voice of soul singer Barry White — had resulted in falling revenues. So, the company took a stab with a more traditional fast food marketing campaign built around a friendly animated character. To still emphasize its carefully roasted beef, the mascot that Arby's and its advertising agency, W.B. Doner and Company, devised was Oven Mitt, a living oven mitt, voiced by actor and comedian Tom Arnold. Arby's committed $85 million to making Oven Mitt a household name. He starred in one commercial, for example, where he got horrifically trapped under a skillet, and another in which he sang the Italian pop song "Volare" to promote an Italian beef sandwich.

Arby's kept pushing Oven Mitt for half a decade, although the campaign slowed down and would eventually end after a disastrous premium drive. In 2004, according to Chief Marketer, the company sold $1.99 Oven Mitt-branded faux oven mitts at Arby's locations, with half the price donated to Big Brothers/Big Sisters. Arby's quickly issued a recall of the promotional item.

The Taco Bell Chihuahua

According to the Los Angeles Times, Taco Bell's campaign featuring a taco-seeking chihuahua that mutters "Yo quiero Taco Bell" was a cultural phenomenon upon its launch in 1998. About 20 commercials starring a tiny dog named Gidget (voiced by "Rocko's Modern Life" and "Reno 911" star Carlos Alazraqui) initially fulfilled Taco Bell's directive to make the restaurant seem like a cool place to consumers in their tweens and 20s. Sales jumped by 3% after the first utterance of "Yo quiero Taco Bell" and by 9% after the chain started selling plush versions of the adorable dog.

As popular as the Taco Bell Chihuahua was, the campaign faced controversy. Marketing firm Wrench filed a lawsuit, claiming that it came up with the idea, and that Taco Bell lifted it without credit or payment. In the summer of 1998, per the Los Angeles Times, the California Coalition of Hispanic Organizations proposed a Taco Bell boycott on the grounds of racism. "To equate a dog with an entire ethnic population is outrageous, despicable, demeaning, and degrading," coalition president Mario Obledo said at the time. Cuban American groups in Florida similarly objected to an ad where the chihuahua wore a beret — perceived as a dig against a revolutionary named Che Guevara.

But then, nobody seemed to like that dog anymore. According to the Los Angeles Times, Taco Bell endured its biggest revenue drop in 2000, prompting the company to fire its CEO and end the "Yo quiero Taco Bell" gimmick.

Dennis the Menace for Dairy Queen

Dairy Queen is in and of itself a nostalgic, all-American brand. The name conjures up images of small towns and summer nights, eating soft serve ice cream and sundaes, a distant mid-20th century memory. To that end, in the early 1970s (according to Brand Channel), Dairy Queen licensed the use of cartoonist Hank Ketcham's wholesome, old-fashioned comic strip troublemaker Dennis the Menace for use in promotional materials and on food and beverage packaging.

Ketcham's images of Dennis, and his friends Joey and Margaret, enjoying Dairy Queen products lasted for nearly 30 years. In 2001, however, Dairy Queen undertook a complete image overhaul, its first in decades. It rebranded its locations with "Grill & Chill," signage, indicating that they served hot food as well as ice cream. At the same time, the chain retired the Dennis the Menace imagery from its stores and packaging but left the door open to return to the campaign should the need arise. "He's taking a nap," International Dairy Queen executive vice president of marketing and R&D Michael Keller told Brand Channel in 2004. "He was a wonderful fit for the brand at a time when the brand, culture, and society were in a different place. He just doesn't have the relevance with today's youth that he had with yesterday's youth."

Speedee for McDonald's

McDonald's wasn't always associated with Ronald McDonald, Grimace, and the Hamburglar, according to Time Out. When brothers Richard and Maurice "Mac" McDonald opened the first McDonald's hamburger stand in 1948, their concept of fast food was so relatively fresh and novel — burgers and fries ready in a couple of minutes — that they needed an advertising mascot to re-enforce the message and clarify their business model. They called their method of ultra-fast preparation the Speedee Service System, and their character bore a similar name — Speedee, a winking, pot-bellied cook wearing a chef's hat and bow tie who had a hamburger for a head. (Early designs also included the character holding a sign that read, "I'm Speedee.")

According to Creative Bloq, Speedee was retired after Ray Kroc took over McDonald's and aggressively expanded the business in the 1950s and 1960s. The company decided to direct its marketing efforts to the idea of the "Golden Arches," a nickname for the restaurants' giant curved "M" logo. That was a response to market research, according to the Journal of the Society or Architectural Historians — the general public had more awareness of the arches than they did of Speedee, so McDonald's speedily dropped him.

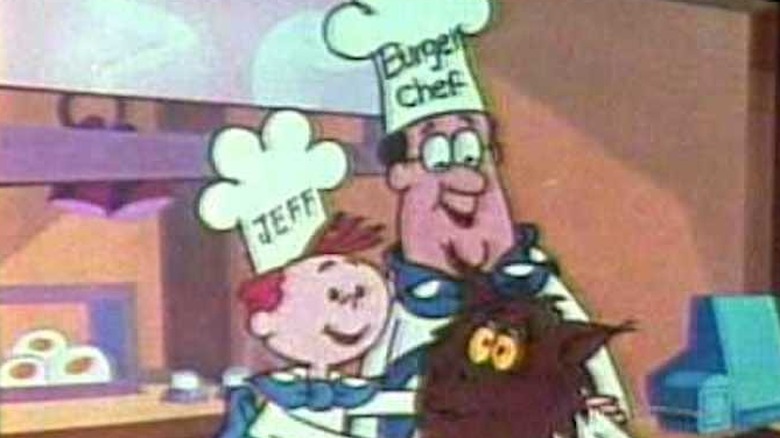

Burger Chef's Burger Chef and Jeff

Burger Chef was once a major fast food innovator and behemoth. According to Reader's Digest, the store invented the combo meal and the kid's meal and grew into a chain of 1,200 locations (via Time) by the early 1970s. At one point, it was the second-biggest fast food burger company. In keeping pace with McDonald's, and its Ronald McDonald mascot, Burger Chef tasked ad agency Carson/Roberts with creating some characters.

According to "Flameout: The Rise and Fall of Burger Chef," the agency hired illustrator Dick Chodkowski, who cooked up Burger Chef and Jeff. The former was the guy in charge of the menu, credited with creating the restaurant chain's most popular menu items, like the Super Shef and the Funburger. "He is warm and lovable," Chodkowski said in the book. "Kind of a fool at times, but always in a way that endears him to people." Jeff, then, was the perpetually awestruck character with a can-do attitude, the Robin to Burger Chef's Batman. "Jeff is a 'gee-whiz' kind of kid," Chodkowski said. "He is always saying things like 'Burnin Burgers' ... 'Flippin' Fries' ... 'Puckerin' Pickles' ... and 'Incredibergible.'"

Burger Chef (and Jeff) are largely forgotten today because the restaurant chain went out of business a long time ago. In 1967, according to the Indianapolis Star, General Foods bought the company and after failing to revitalize it, sold the operation in 1982 to Hardee's, which absorbed and converted what Burger Chef outlets remained.

The Quiznos Spongmonkeys

One night in the early 2000s, according to Mel Magazine, animator Joel Veitch of the Rathergood production company, got drunk with his brother at a pub in the U.K. "We were talking about how great the moon was while we got a bit tipsy," he told the magazine. Still inebriated, they went home and videotaped themselves singing a silly song about the moon. The next day, he thought the song was funny enough to turn into a cartoon featuring characters he'd been developing called Spongmonkeys — at the time, Veitch was playing around on a social media site where adding bug eyes to pictures was called "sponging." The video became a viral hit on the Internet in the pre-YouTube days, and within a few months, hot sandwich chain Quiznos reached out to Veitch to use his Spongmonkeys — grotesque little furry creatures with strange eyes — in an American ad campaign. Veitch and his brother simply rewrote the lyrics about the moon to be about sandwiches.

The briefly airing ads both worked and didn't for Quiznos. The Spongmonkeys increased the company's profile but also inspired a lot of complaints. The Quiznos corporate office registered 30,000 calls from angry customers in the first month of the campaign, while one Alabama store (via Denver Business Journal) posted a sign on its doors denying responsibility for the Spongmonkeys ads.

Rax's Mr. Delicious

Rax restaurants specialized in roast beef sandwiches. The chain was slowly dying out in the early 1990s, and the company tried several things to save itself, like including a salad bar (according to Restaurant Finance) and rolling out an objectively and purposely odd advertising campaign that relied on dark, ironic humor. According to The New York Times, Rax announced its "Mr. Delicious" marketing plan in August 1992. Created by the Deutsch Inc. advertising agency, the idea was to position Rax as a fast food outlet for adults. And Mr. Delicious was decidedly an adult — middle-aged, balding, and wearing an unstylish plaid suit, bow tie, and thick eyeglasses. In commercials, he complained about his financially disastrous divorce, his anger management issues, and his vasectomy, according to BoingBoing.

In order to sell the operators of its faltering franchises on the Mr. Delicious campaign, Rax and Deutch produced and distributed a 13-minute tongue-in-cheek documentary about the character. "I know what you're thinking. He's a cartoon, and cartoons are mostly for people who wet their pants. But not Mr. D.," the character explained in the short film. "He's a special cartoon for adults. Diggity-dee!" The mascot was a massive miscalculation. The off-putting and bizarre Mr. Delicious couldn't rescue Rax, which filed for bankruptcy three months after the character's debut.

A&W's Rooty the Great Root Bear

A&W, the chain of restaurants specializing in hamburgers, fries, and its flagship root beer, claims to be the original fast food chain, having started out as a single root beer stand in Lodi, California, in 1919 before expanding into the first franchised quick-serve restaurant. But by the early 1970s it had lost so much market ground to McDonald's that it hired a Toronto-based advertising agency to revitalize the brand. The ad company's solution: a kid-friendly, ad-friendly mascot: Rooty the Great Root Bear, whose name was a play on "great root beer." Debuting in marketing materials in Canada in 1974, according to the CBC, Rooty had brown fur and wore an orange hat and sweater that matched the colors of the A&W logo that adorned his chest.

Rooty almost never made it to the U.S., per MeTV, where market research indicated he'd be a flop. A&W's marketing director ignored the test results and signed on anyway. Before long, Rooty popped up in TV ads, and most every A&W outlet began selling merchandise bearing Rooty's image, including root beer mugs, stuffed animals, and clothing, all the way until the 2000s.

Bad Andy for Domino's

In the '80s, the Domino's clay-animated ad mascot The Noid tried to prevent pizzas from being delivered. In the early 2000s, Domino's puppet mascot Bad Andy did his best to ensure that Domino's employees never made the pizzas at all. According to Yahoo! News (via Muppet Central) Bad Andy was the central figure in "Bad Andy, Good Pizza," a Domino's TV, radio, and print campaign launched in May 2000. The idea of ad agency Deutsch, Bad Andy was created and built by The Jim Henson Company, and he was a nonverbal monkey-like creature who lived to create chaos at his job at a Domino's. In one TV commercial, for example, he plugged in a massage chair and a bunch of other appliances to prevent the restaurant's pizza-warming bags from getting heated; in another, he attempted to talk a coworker into using a rolling pin on pizza dough rather than stretching it by hand.

In March 2001, less than a year after it set Bad Andy loose, Domino's ended the campaign, according to the Houston Chronicle. "Bad Andy simply didn't get the job done for us," Domino's acting executive vice president of brand marketing Patrick Doyle said at the time. Indeed — with "Bad Andy, Good Pizza" in play, chainwide sales at Domino's dropped by 2%, per the Houston Chronicle.