In Mexico, Corn Is Life Slideshow

The first thing I eat when I get to Mexico is a wonderfully toothsome roasted ear of local corn slathered with a thin layer of crema (Mexican cream), sprinkled with powdered red chile, and moistened with a squirt of fresh lime juice. Sometimes the cooked kernels are removed from the ear, given the same treatment, and are sold as esquites.

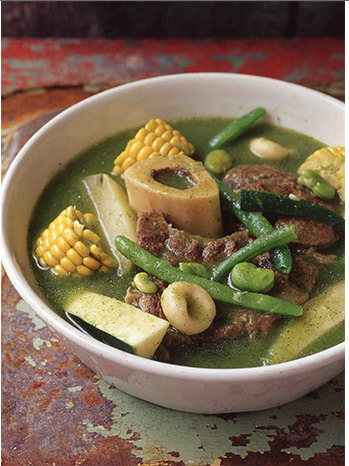

Vegetable-Filled Soup-Stews

Fresh corn is consumed in Mexico mostly in soups — or soup-stews — such as chileatoles, chilpacholes, and tesmoles (pictured here). These vegetable, seafood, poultry, or beef broths contain lots of fresh vegetables that vary by region and season. There might be chayote, carrots, cabbage, potatoes, peas seasoned with local herbs, salsas made from tomatillos, cilantro, and jalapeños, or red chile purées. Fresh lime juice makes all the flavors come alive. Ears of corn, cut into pieces, are sometimes added, but many of these soups are also thickened with ground corn.

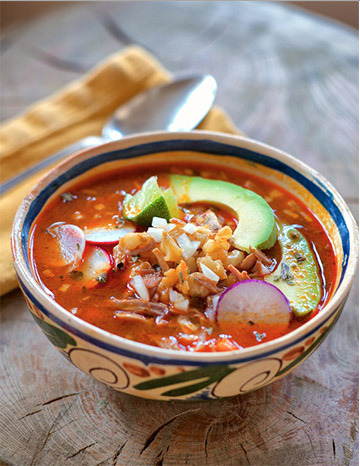

Hearty Pozole

Then there is pozole — the word applies both to the nixtamalized grains of corn — what Americans call hominy — and to the stew made with it (pictured here). There are many regional varieties of pozole, depending on the area and the variety of corn used. Though it is extremely hard to find now, cacahuazintle (white dent corn) is the traditional variety for this satisfying dish. Probably the best known pozole is that of the state of Jalisco, made with pork — jowls and all — or pork and chicken together.

You can order this pozole "rojo" (or "colorado") — red — with a red chile paste added, or "blanco," with no chile. What I love about this dish is that you dress it with all sorts of garnishes such as sliced radishes, oregano, sliced limes, shredded lettuce, avocado, tiny dried red chiles (like chiltepines, wild chiles) that are crumbled and toasted, and in some places chicharrones (fried pork skins). Most important is chopped onion. (My mother poured boiling water over the onion, patted it dry, and seasoned it with fresh lime juice and Mexican oregano that she rubbed between her hands to grind it finely and release its aroma; this process is called desflemar, to remove bad fumes.) Each element adds a new flavor or texture. The state of Guerrero is famous for its green pozole. (The other most famous Mexican soup made with pozole is menudo, the famous hangover cure eaten all over Mexico — tripe soup made with pozole.)

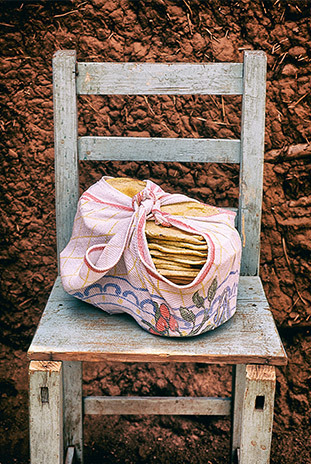

Making Tortillas

All over rural Mexico, people wake up to the joyful clapping sound of someone making corn tortillas. The aroma emanating from a tortilla cooking on a griddle heated by a crackling wood fire is the only alarm anyone needs. A meal in Mexico without tortillas is unimaginable. But tortillas are different in every place, and only a few tortilla-based dishes are available nationwide — principally tacos, tostadas, chilaquiles, sopes, gorditas (puffy little fat tortillas), and totopos (tortilla chips).

Though it's not easy to find in the U.S., the best masa is made with varieties of Mexican corn that contain a soft starch that gives dishes a luscious quality — a lovely, satisfying chewiness. Tortillas made with masa from such corn are the perfect vehicle for fillings, toppings, and such because it doesn't dry out and crack. Corn grown in America has harder, firmer starch. Products made from it are not as satisfying; they're dry and don't hold up as well.

Native Corn

Indigenous corn varieties are being rescatadas (rescued) by people all over Mexico who are in a constant battle, led by Oaxacan artist Francisco Toledo, with Monsanto, which is vying to plant genetically modified corn on a large scale in the country. Oaxacan landrace corn (domesticated traditional varieties that have adapted to different regional conditions), such as bolita, comiteco, chalqueno, and olotillo (there are some 60 varieties in all in the region) are now available for sale in the United States — but ironically not in Mexico — thanks to the tireless and dedicated work of Jorge Gaviria and his partner Kate Barney, who own www.masienda.com. Their corn is championed by chefs such as Enrique Olvera at Cosme and Roberto Santibañez at Fonda, both in New York, and Rick Bayless at his various Chicago restaurants, and by a growing number of others around the country. (The first chef I saw making her own masa, with corn brought from Sinaloa, and turning it into fresh corn tortillas hot off the griddle, was Sue Torres at the now-closed Suenos restaurant, back in 2004.)

Discovering Corn

When the Spanish landed on the shores of Veracruz in 1519, they tasted corn for the first time and took to it immediately. They particularly liked the flat corn masa cakes called tlaxcalli in the Nahuatl language, which they renamed tortillas, little cakes; the soft mounds of dough wrapped in various kinds of leaves and steamed or cooked on a griddle, tamalli, became tamales.

World Influences

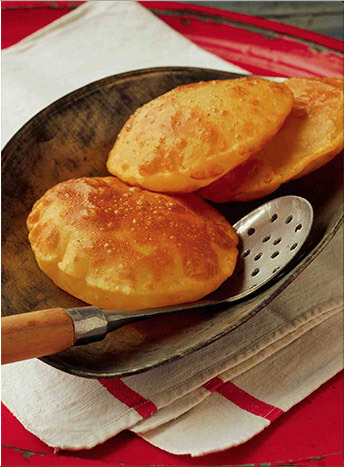

When the Spaniards mixed corn masa with lard from the pigs they had brought with them, the Veracruz corn kitchen we know today was born. But the Spanish brought much more than pigs. With them also came cattle, chickens, wheat, olive oil, Old World spices, wine, pickling techniques — and from their time in the Caribbean and in the African slave trade, plantains, coconuts, yams, and other root vegetables. These ingredients gave rise to an incredible variety of tortilla derivations, such as simple tortillas made from masa with added shredded green plantains or mangos or the puri-like gorditas infladas (pictured here) that puff up when fried if a little wheat flour is added. Some of these are sweet from ripe plantains; others are savory when the masa is mixed with black beans. Cooks pinch the edges of a tortilla to hold puréed beans, a spicy sauce, or both. With a sprinkling of dried queso fresco and a dab of crema, these are good any time, but in Veracruz, they are served in the morning. In the Los Tuxtlas region of southern Veracruz state, larger thicker pinched tortillas are called pellizcadas and are commonly spread with asiento, the residue that accumulates from rendering lard or making pork cracklings (chicharrones).

A Versatile Salsa

In northern Veracruz, freshly made tortillas are dipped in a spicy pumpkin seed sauce to make enchiladas huastecas. In other places, tortillas are dipped in peanut sauce (encacahuetadas) or finely puréed refried beans (enfrijoladas).

When some sort of chile sauce, be it green or red, is used, of course, the result is enchiladas. My favorite ones are my mother's red chile enchiladas, made with the versatile salsa de chile colorado (pictured here), but a close second are the enchiladas del Istmo from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Oaxaca state. These are stuffed with a pork picadiilo made with plantains and some fresh or dried fruit in an intense ancho chile sauce. Everyone's favorite green enchiladas are enchiladas suizas, with their layers of salsa verde, cream, sautéed chicken, and cheese.

Masa Mixed With Yams

In Veracruz and elsewhere there is also a huge variety of fried snack foods such as the boat-shaped guarachas (pictured here), a specialty of Tlacotalpan's Restaurante Doña Lala, made of masa mixed with yams and topped with chorizo, slightly pickled onions, and queso cotija. In other parts of the country, garnachas are tortillas puffed up on one side, with that side carefully opened and stuffed with assorted fillings, before the whole thing is lightly fried. Other regional antojitos include tapaditas de frijol from Coatepec in central Veracruz, fat, round corn "pastries" known as gorditas in other states; and miniature gorditas, called aspirinas (aspirins), in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco — fried tortillas that puff up and have an assortment of fillings put into a slit in one side. In the northern state of Chihuahua, where I grew up, we stuff them with a simple beef picadillo, topped with very finely shredded minty cole slaw and a squirt of liquid chiltepin sauce.

Red and Green

Then there are picadas (pictured here). Picada, literally "pinked" or "pricked," refers to the way the edges of a small tortilla are crimped so as to form a shallow tartlet shell for spreading with a few simple toppings. Picadas are served as either a breakfast or supper snack. You may have encountered similar masa preparations, in different shapes and sizes, under names like "sopes" or "chalupas." Picadas usually come to the table in Veracruz in colorful pairings of red and green: one shell spread with salsa colorado or chipotle sauce, its mate with some kind of salsa verde. The other toppings (usually crumbled or grated cheese and Mexican crema, sometimes also a little chopped onion) are arranged over the sauce. Some people add shredded meat as well, but I think it distracts from the simple flavor of the sauce.

Oaxacan Tortillas

In Oaxaca state, there is another, generally healthier treasure trove of corn specialties. Here, the most famous tortillas are blandas, over-sized, somewhere between 12 and 15 inches in diameter, soft and fine. These may be used to make empanadas de amarillo, stuffed with shreds of Oaxaca cheese, squash blossoms, and mole amarillo (yellow mole). The hearty, chewy, infinitely satisfying clayudas, or tlayudas, usually get a smear of asiento and are topped with a wide assortment of additions at little markets, stalls, and restaurants where people eat them like we do pizza. I like to toast the tortillas slowly and dip them into a smoky blistering hot sauce or guacamole sprinkled with crispy, tart fried grasshoppers.

Mexico's 'Truffle'

The most unusual corn product used in Mexican cooking is huitlacoche, or cuitlacoche (Ustilago maydis), which is corn smut, a type of fungus that invades the growing ears of corn, causing the kernels to swell into gray or blue-black masses (as pictured here). Farmers take vigilant measures against it in the United States, and home gardeners throw away "smutty" ears in disgust. In Mexico we consider it our truffle!

Fresh huitlacoche is rarely sold retail in the U.S., though it can be bought in the American Southwest and at some supermarkets with a Mexican clientele. When it's found growing on corn in most parts of this country, it is completely different from the Mexican product; the kernels of U.S. sweet corn yield a milder-flavored huitlacoche than Mexican varieties. I hope that fresh huitlacoche will one day be widely available throughout the U.S., as are such other once-exotic foods as kiwi fruit and jicama. Meanwhile, you have to hunt for it. There is, however, a canned version, sold seasonally under the Herdez, Goya, and San Miguel labels, and available at Mexican grocery stores and from online specialty purveyors.

From Masa to Tamale

For Mexicans, the ritual of making tamales (pictured here) is usually a family affair. Each part of the process has to be lovingly done by hand. The lard should ideally be home-rendered. I live in New York, where luckily you can find anything, but many tamal-lovers live in places where no fresh masa is available and they must resort to masa made from masa harina (corn flour). To make up for masa harina's failings, I suggest that you reconstitute it with chicken stock for additional flavor and then beat it with home-rendered lard until it's fluffy and almost ethereally light. (Test it by dropping a dollop into a glass with cold water; if it floats, it's light enough.) The masa will usually be spread on either corn husks that have been soaked in hot water until softened, or mounded on squares of banana leaves and topped with a filling of some sort. Each kind of leaf will dictate how you fold it over. Banana leaves are normally stiff and dry easily, so I like to make little gift-shaped squares tied coquettishly with a ribbon of leaf scraps. Some chefs do that with regular tamales but I think it is too precious, and untying the corn husk ribbons delays the pleasure of savoring the fluffy masa. But be forewarned that if you used any other fat instead of lard, your tamal may be more like a brick!

Unusual Tamales

The king of tamales is the sacahuil of northern Veracruz. There are two varieties: the traditional one and the quite spectacular six-foot-long bullet-shaped sacahuil from the upper Huasteca. Considering the size of my New York kitchen, I make the former, and have to restrain myself and invite fewer people to share this wondrous dish.

My other favorite Veracruzan tamal is the tamal de cazuela (pictured here), a dish with layers of pre-cooked masa. In this method, you thin the masa with homemade chicken stock and strain it into a large pot (you might have to strain it more than once if the masa is very coarsely ground). You'll then add melted home-rendered lard and salt, stirring well to combine the ingredients, and cook it, stirring slowly at first, until the dough forms into a large gleaming ball of deliciousness. You'll need to work fast and pat half of the dough into a casserole (the masa is hard to work with if it cools too much), then spoon in picadillo or stewed chicken or pork in a mole or other cooking sauce, and finish the dish with the remaining masa. If not planning to eat this tamal right away, you can cover it tightly and refrigerate it until you're ready to heat it through and serve it.

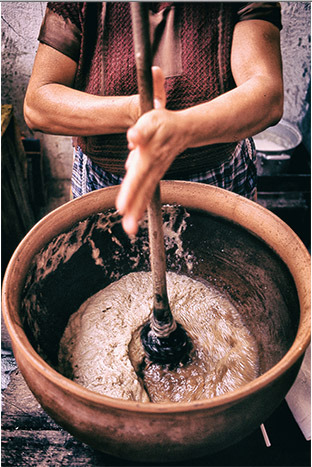

We Even Drink Corn

The traditional beverage to drink with tamales is atole , an unappetizing-sounding, but comforting and nourishing, corn masa gruel. My mother always made it on rainy or bitterly cold days at the ranch, and many markets and stands all over Mexico sell it for breakfast. A delicious variation is chocolateatole (pictured here), also called champurrado, made by whipping plain atole and hot chocolate together with the molinillo, a wooden whose loose rings of different thicknesses whirl rapidly when the contraption is quickly rolled between the palms of the hands. (Sadly, many people now use packaged atole mixes in a variety of artificial fruit flavors with corn starch as the base — a far cry from the original.)

There are many other corn-based beverages in central and southern Mexico. In Chiapas, tascalate is made with toasted corn, chocolate, achiote (annatto seeds), vanilla, and sugar — a beverage wonderfully refreshing in the hot areas of the state and comforting in the mountainous areas. In Oaxaca, a drink of Zapotec origin is also made with toasted corn but includes grated mamey (sapote) pits and the aromatic rosita de cacao, or little cacao rose (which has no connection to cacao other than its name).

I don't have much of a sweet tooth and, in general, corn desserts do not thrill me. I do love the toasted grainy corn cookies from Oaxaca called pimpo. The pemoles of Veracruz, made with masa harina, are less exciting, though still good, and the sweet torta or pastel de maíz is good not only as a dessert but also as a breakfast bread. I love popcorn and corn balls with piloncillo (unrefined cane sugar) syrup, but I have not learned to crave either corn paletas or corn ice cream. Just give me one of my mother's sweet tamales and I'll be satisfied.