The 50 Most Important Inventions (And Discoveries) In Food And Drink

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

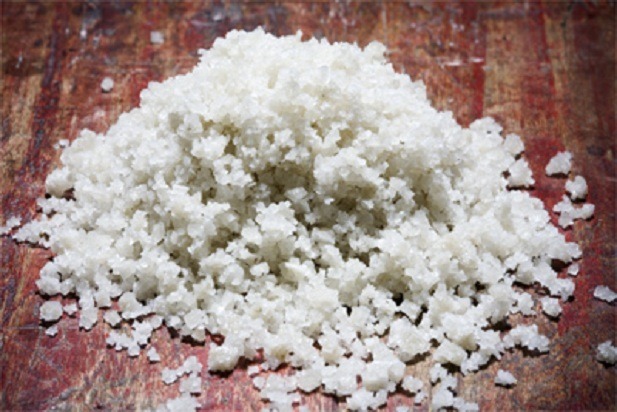

Salt

It was there all the time, of course, in rocks, in the ocean, in us... Our early ancestors must have noticed the pleasant tang of seawater, and maybe the way it preserved the dead things that floated in it, and at some point — at least 8,000 years ago but probably earlier — they figured out how to extract the salt. The next thing anybody knew, the salt trade and salt taxes were changing history; we were eating salads and collecting salaries; our food lasted longer and tasted better, and our blood pressure was through the roof.

Fire

The earth was formed in fire, sort of, though not the kind you'd make S'mores in front of. Then things cooled down and people appeared and enough oxygen developed to allow a milder sort of flame. Archaeologists have found the remains of cooked food dating back almost two million years, but this might have been opportunistic: "Hey Oog, lightening kill bird, smell good, let's eat!" Our ancestors probably first figured out how to start (and, we hope, stop) fire at will about 400,000 years ago, and real cooking, with all that that entails, became possible.

The Knife

The knife is considered to be the oldest human tool. Of course, we're not talking stainless-steel Wüsthofs here — more like hunks of obsidian or flint with their sides chipped into sharpness. Metal started coming into the picture around 2500 B.C., and the design and quality of blades fixed in handles became better and better. Knives may be our oldest tool, but they remain our most important for rendering food edible, usable from field or forest to kitchen to plate.

The Spoon

How on earth did people eat soup before spoons were invented? Or ice cream? Food for thought. Spoons are ancient, in any case, though not as old as knives. The first ones were either hollowed out bits of wood or maybe small seashells or nut hulls (bigger ones were the first cups). The old-time Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans used elaborately fashioned and decorated spoons, but the modern version, with tapering bowls and long handles, didn't appear until the mid-18th century. Today, we not only eat but measure and stir with spoons, and of course they're also essential for flinging globs of Jell-O across the room.

The Pot

Without pots — and their flatter brethren, pans — our cooking options would be fairly limited. (Will you have that roasted or grilled?) That must have dawned on our prehistoric ancestors, because there is archeological evidence of early attempts to cook food in vessels made of stone, turtle shells, clay, even wood treated to withstand flame. Fire-hardened clay or earthenware vessels first appeared more than 15,000 years ago. Metal pots appeared soon after metal did, and by medieval times kitchens were typically stocked with iron pots, kettles and cauldrons whose basic design we would recognize today. The next thing you know, everybody was registering for that complete set of Calphalon.

Fermentation

Fermentation, in the food and drink sense, is simply the conversion, by yeast or bacteria, of carbohydrates into alcohol and carbon dioxide. It occurs naturally: Leave fruit in a bowl for long enough and quite possibly the juice will ooze out, meet airborne yeast cells, and start fizzing, producing something that is technically wine, and probably tastes a lot like cheap Chilean Merlot. The human trick was learning to control the process and apply it to the making and/or preservation of all kinds of stuff — not just wine, beer, cider, and mead, but vinegar, yogurt, cheese, some sausages, sauerkraut, and kimchi, among other things without which life would not be worth living.

The Mortar and Pestle

This one-two punch of food preparation — a bowl of metal, stone, wood, or ceramic into which fits a blunt crushing tool — was known to the Romans a couple thousand years ago and also to the Aztecs (who called it a molcajete). Other early interpretations were used in India and Southeast Asia. In Europe, the mortar and pestle was first mostly a tool with which pharmacists crushed and mixed medicinal herbs and spices. Many cultures still use it to pulverize leaves and pods for cooking, and of course no sensible Italian would think of making pesto with anything else.

The Fish Hook

The earliest fish hooks, made out of wood or bone, date back at least 9,000 years. The use of metal for hooks and later the mass production of them standardized the basic designs. Most commercial fishing no longer depends on such rudimentary technology — though "line-caught" has become a buzzword on restaurant menus — but the impact of the fish hook on the ability of humans to sustain themselves cannot be underestimated. (And what about the spear, the bow-and-arrow, the gun? you might ask. Sure, they've helped us assuage our hunger too, but unlike the fish hook they are also instruments of conflict, facilitating conduct that is, frankly, pretty much the opposite of harvesting dinner.)

The Barrel

The French (okay, the Gauls) may have made the first wooden barrels, figuring out how to heat and bend staves of wood and bind them into pot-bellied form with rope and later metal bands. The Romans adopted the idea, finding barrels a great improvement over the clay pots and amphorae they had been using for wine, oil, and other substances (they were bigger and more stable, and didn't have to be sealed with resin). Barrels turned out to be ideal for storing and shipping everything from wine and whiskey to pickles, olives (and their oil), herring, and cured pork.

The Fruit Press

To get wine out of grapes, cider out of apples, and oil out of olives (among other things), you must crush the fruit really hard. The first presses for these purposes were apparently beams with platforms on one end onto which heavy stones could be loaded. The screw press, dating from around the third or fourth century A.D., was a major improvement; it could be turned by man or beast with a lot less energy than hefting big rocks around required. Today, of course, electricity is involved — but the basic idea remains the same.

Chopsticks

Chopsticks — whose name apparently derives from a Pidgin English term meaning "fast" — originated three or four thousand years ago in China and subsequently became popular eating utensils throughout Asia. They're basically tongs that use the human hand as a hinge and are often made of bamboo resistant to heat. Knowing how to use chopsticks properly is now considered an elementary skill among non-Asian food lovers.

Canning (and Can Opener)

In 1795, Napoleon "An army travels on its stomach" Bonaparte offered a cash prize for anyone who could devise a way of preserving food for his soldiers in the field. Fourteen years later, chef and confectioner Nicolas Appert stepped up to claim the reward — not with cans but with sterilized bottles. Actual tin-plated cans — so sturdy that they reportedly had to be opened with a hammer and chisel (and sealed with lead, which tended to poison frequent canned-food eaters) — first appeared in England in 1818. Forty years later, Ezra Warner of Connecticut patented the first metal can opener. Spam arrived in 1926.

Distillation

If you boil the water out of murky water, only the murk remains — and if you collect the water, you've got distilled water. The Greeks starting doing that about 2,000 years ago. Arabs in the ninth century refined the process and invented the alembic still, variations on which are used to this day, though mainly to make perfume. A 13th-century Valencian physician and alchemist named Arnaud de Villeneuve is often credited with having figured out that if you distilled wine, boiling off all that pesky water and getting down to the good stuff, it was probably going to be party time. Brandy, whisky, and (much later) Grey Goose L'Orange appeared subsequently.

The Fork

Forks used to be farming tools (think pitchfork) and then maybe cooking tools (food wouldn't slip around on the spit if the spit had two prongs instead of one). Smaller forks, for spearing pieces of meat and other foods at the table, most probably weren't widely known until at least the tenth century A.D., and didn't become standard tableware in Western Europe until 1400 or so — way after chopsticks.

The Restaurant

The earliest restaurants — as opposed to inns, which were places you'd stop on the way somewhere and hope there was a pot of stew on the fire — seem to have appeared as early at the ninth or tenth century A.D. in both China and the Islamic world. On the other hand, the word 'restaurant,' from the French verb restaurer, meaning to restore (presumably meaning to make you feel better), dates from Paris in 1782, where it was coined by a Parisian gastronome named Antoine Beauvilliers. He opened the Grand Taverne de Londres in the French capital with a chef poached from the aristocracy and a menu that actually let customers choose what they wanted to eat (a quaint custom which has since disappeared in many trendy eateries). Pictured here: The French Laundry.

The Scale

Weight is a measure of worth in oh, so many ways. Elementary balance scales were being used in southern Asia 5,000 years ago. Spring scales didn't come into common usage until the mid-19th century, at which time they promptly became indispensible on farms and in retail shops among other places. Accurate electronic digital scales are a child of our own time, not much more than 20 years old. Though many chefs and home cooks scorn precise measurement in preparing food, scales are essential, for presumably obvious reasons, in commercial food production and in baking (even at home) — and are also required for the realization of most so-called "molecular" creations.

The Threshing Machine

Andrew Meikle, a Scottish millwright, invented the thresher in 1778, as a way of mechanically removing grain from its husks; it didn't work very well, but he kept trying and a few years later he finally got it right. Threshers separate wheat, peas, soybeans, and other small grain and seed crops of every kind from their chaff and straw, and are a key component of modern agriculture.

The Cork

Cork is the outer layer of Quercus suber, the cork oak, a tree widely found in Portugal (which produces more than half of the world's cork) and around the Mediterranean basin. This pliable, porous pith creates a perfect barrier between liquids and air, and as early as the 1700s cork began to replace oil-soaked rags as a stopper for containers of wine and spirits. The first corkscrew, which arrived around the same time (fortunately), was apparently inspired by the gun worm, a device designed to extract bullets from rifle barrels. After all these years, cork is slipping at least a little out of fashion as screw-cap bottles become increasingly popular, even for premium wines. Cork-soled shoes, on the other hand, are all the rage.

The Rolling Pin

The Etruscans used stone rolling pins 3,000 years ago, and clay and wood cylinders have been utilized for centuries in various parts of the world to flatten dough, crush grains and herbs, and perform other culinary tasks. A man named J.W. Reed invented the standard modern rolling pin, with the roller pierced by a central rod attached to handles on either end, in the late 19th century.

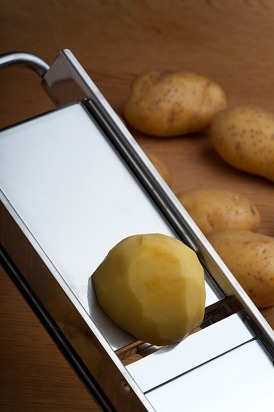

The Mandoline

The hefty culinary tome called Opera dell'arte del cucinare, published in 1570 by Vatican chef Bartolomeo Scappi, depicts a board with a series of inset blades for cutting food (it also contains the first-ever published image of a fork). Variations on the instrument — named, though probably not until the 20th century, after a musical instrument, the mandolin — became common in European kitchens thereafter. The first metal mandoline was invented in France in the early 20th century. Some chefs scoff that they can cut and slice as neatly with a sharp knife. But they can't.

Tongs

The first tongs were probably just two unattached sticks used way back in prehistory to pick up hot food. Somebody, somewhere along the way, figured out how to attach them with a hinge, and by around 3000 B.C., metal tongs not unlike the ones we now use appeared. Tongs of whatever design are today more or less an essential instrument in nearly every kitchen, professional or otherwise.

Parchment

The original parchment, translucently thin animal skin prepared as a medium for writing, was probably never used in cooking; it would have burned. So-called baker's or cook's parchment may have been inspired by the look and feel of the original, but is actually heat-resistant, non-stick, silicone-coated paper, used to wrap food for baking or as a disposable non-stick surface. A variation, wax paper, invented (for non-culinary purposes) by French photographer Gustave Le Gray in 1851, is useful for food prep but doesn't do very well in the oven.

The Grater

Knives cut, but to render firm foodstuffs (cheese, lemon peel, raw vegetables, etc.) into shreds or powders, a grater is the thing. The first one, made of pewter and designed to turn rock-hard cheese into something edible, was invented in France in the 1540s by one François Boullier. Many variations have ensued, among them the four-sided love-it-or-hate-it box grater and the newly trendy Microplane. The latter, based on the carpenter's rasp, was invented in the 1990s by Arkansas toolmaker Richard Grace.

The Gas Oven

Wood-fueled ovens date far back into prehistory, and though designs improved dramatically over the centuries, they were still the only cooking option, even indoors, in many parts of the world — where there were no gas lines — through the mid-1900s. The earliest known use of the gas oven, however, was at a dinner party hosted by Moravian chemist Zachaus Winzler in 1802. In 1834, British inventor James Sharp began selling the first commercial gas ovens, and by the 1920s, appliances outfitted with thermostats and coated in enamel for easier cleaning were common.

Pasteurization

The idea of heating food, whether solid or liquid, to inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, goes back hundreds of years, and may well have been first figured out in Japan or China. Controlled heat-treatment, designed not to kill all living things food might contain but to limit the number of potentially problematic microorganisms, was developed by the French chemist Louis Pasteur and his physiologist colleague Claude Bernard as a means of stabilizing wine. It came to be commonly used to treat not just wine and beer but dairy products, canned foods, and even bottled water.

Refrigeration

For eons, we've been trying to keep food and drink cold (and thus slow to spoil) with things like chilly streams, stockpiled ice or snow, and evaporation techniques. Ice boxes, with sophisticated insulation systems, became popular in the early 19th century, and various vapor-compression and gas-absorption refrigeration systems soon followed. German engineer Carl von Linde is often credited with developing the first modern-style refrigerator, which he patented in 1877. The first electric home refrigerator was sold around 1915, and by 1920, there were some 200 models on the market. Refrigeration has changed the way food is packed and shipped and of course the way we shop and eat.

Recipes

People have presumably shared cooking lore for as long as they've cooked, and such information was first written down (or at least etched into clay tablets) as long ago as 1600 B.C. in Babylonia. Greek and Roman gastronomes described dishes in detail, and the first actual recipe books first appeared in 14th-century England. Recipes in the modern sense, though, giving precise measurements, step-by-step instructions, and tips on technique, are a fairly recent phenomenon, becoming popular after the first publication of such classic volumes as "The Boston Cooking School Cookbook" (1896) and the inevitable "Joy of Cooking" (1931). In the modern age, when we no longer learn how to cook at Grandma's side, recipes have become essential; some folks can't make toast without them.

The Thermometer

Scientists in antiquity tried various methods of measuring temperature, and Galileo designed a kind of proto-thermometer around 1593, but the calibrated mercury thermometer was the invention of Daniel Fahrenheit in 1724. Thermometers may have first been used in food preparation by professional candy makers in the 1800s, but it wasn't until the 20th century that smaller versions became available for home kitchens and the USDA started telling us to make sure that chicken thigh had reached 165ºF.

The Dehydrator

A prototype of the modern food dehydrator was invented in France in 1795, but the first commercial home models were sold only in 1920. Dehydration mechanisms have many applications in commercial food production, but on a smaller scale they were mostly used by survivalists, campers, and raw-foodies until recently. Lately, both avant-garde chefs and their associated non-professional wannabes have been using dehydrators for various kinds of "molecular" mischief.

Extruder

Extruders, which push soft material through a die, were first used by metal-workers in the late 18th century. The earliest application of the devices to food production can be traced to pasta-makers in the 19th century. Today, extruders are responsible for fashioning not only pasta in hundreds of shapes and sizes but also everything from licorice sticks to commercial croissants to Kibbles 'n Bits.

The Coffee Maker

Not one of the 50 most important inventions in food and drink? Oh yeah? Try getting to work without it. You don't need a coffee maker to make coffee, of course; since somebody discovered the stimulant effects of coffee beans in the 15th century, people have been simply boiling the grounds with water (which is how coffee is still brewed throughout the Middle East). But machines are so much easier at 6:30 in the morning. The earliest example may have been the hourglass-like vacuum-brewer, developed in the mid-1800s. The electric percolator was patented in 1889. Later came drip coffee makers, like the famous Mr. Coffee (first sold for home use in 1972), and espresso machines (the original one was patented in 1901), among other caffeine-delivery devices.

The Deep-Fryer

Frying means cooking food in oil or fat and deep-frying means cooking it in lots of oil or fat. It is obviously possible to do this with just a pot and a flame and some tongs or a slotted spoon, but a particularly deep pot with an inset basket and a means of controlling temperature obviously does the job best. Anetsberger Brothers, a New Hampshire-based kitchen equipment company, is credited with having introduced a countertop version of exactly that in 1937. We've all been eating far too much fried food ever since — but who's complaining?

The Induction Cooker

Surprisingly, the electric range is almost as old as its gas-fueled counterpart — but it didn't come into common use until the 1930s. Induction cooking, which heats pots and pans directly by with an oscillating magnetic field, is in turn almost as old as its electric counterpart — it was first demonstrated in 1933 at the World's Fair in Chicago — but has only recently gained wide popularity. It is considered safer than other cooking methods (no more flaming kitchen towels!) and is considerably more energy efficient. Almost 85 percent of the energy it produces is transferred to the food being cooked, compared with around 40 percent for a gas range.

The Microwave Oven

Invented by accident when American engineer Percy L. Spencer of the Raytheon Company noticed that a chocolate bar in his pocket melted while he was experimenting with radar tubes (the first food he deliberately cooked this way was popcorn), the microwave may very well be the most influential kitchen invention of the 20th century. The Amana Corporation marketed the first home microwaves in 1967; today 75 percent of American households claim that living without the things would be "almost impossible/pretty difficult."

Kitchen Wrap

Plastic wrap was first synthesized accidentally by DOW chemical engineer Ralph Wiley in 1933. Although initially used to wrap military equipment, its value as a food preserver quickly became apparent. The advantage? It sticks to almost anything. The disadvantage, at least for frustrated home chefs? It also sticks to itself. Plastic wrap's main competitor for the wrapping of food at home, aluminum foil, was originally tin foil — and some folks still call the former by the latter's name. Aluminum foil was introduced in Europe just after 1900, and unlike its predecessor, does not lend a metallic tang to food. Unlike plastic wrap, aluminum foil withstands heat, so can be used in the oven to protect pan bottoms or keep food from direct heat.

The Pressure Cooker

A device that raises the temperature at which water boils, the pressure cooker dates back to the 17th century, when French physicist Denis Papin showed off an early version, which he called a "steam digester," by fixing a gourmet meal for the royal court. Mass production waited until just after World War II, when the device caught on with homemakers who saw it as an easy way to cook complex meals. It is sometimes considered a little old-fashioned today but remains an easy and fuel-efficient tool for cooking all kinds of things.

The Egg Carton

In 1911, hearing a hotelier's complaint that the eggs he bought from a local farmer always arrived broken, Canadian newspaperman Joseph Coyle designed a paper carton with dimples to hold each egg individually and cushion it against bumpy British Columbia roads. The materials used have changed, as have fine points of design, but the egg carton remains the only safe and inexpensive way to transfer the fragile-shelled ovoids from one place to another.

Gelling Agents

Nobody knows who first discovered that certain substances, when stirred into food, would cause it to thicken and/or stabilize and/or "set," but the technique has since been applied to all kinds of foods, including (but hardly limited to) beverages, soups, sauces, ice cream and other desserts, and Ferran Adrià's spherified olives. Avant-garde chefs like Adrià and Wylie Dufresne, who use gelling agents frequently in their cuisine, are often accused of cooking with "chemicals" — but most gelling agents are natural substances, among them carrageenan, agar-agar, and various alginates (all derived from seaweed), and vegetable-based locust bean and xanthan gums.

The Vacuum Sealer

If you want to keep food fresh and safe, air is the enemy. Vacuum sealers get the air out. Industrial sealers were invaluable during World War II, helping to preserve food for shipment to U.S. forces overseas. After the war, the machines were adapted for use in commercial food production facilities, supermarkets, and restaurant kitchens. One common use of vacuum sealing today is in sous-vide (literally "under vacuum") cooking. This technique was first conceived by physicist Sir Benjamin Thompson in 1799, but the idea languished until the mid-20th century, when scientists developed it for commercial food production. French chef George Pralus, working with chefs Pierre and Michel Troisgro at their three-star restaurant in Roanne, introduced it to the world of haute cuisine. It has since become vital to the kitchens of star chefs like Ferran Adrià, Heston Blumenthal, and Thomas Keller.

Tupperware

Named for its inventor, Earl Tupper, the food-saving polyethylene package with its famous "burping seal" was first sold in Massachusetts in 1948. Three years later, with a couple of salesman, Tupper began organizing Tupperware parties, and a national craze was born. Tupperware remains so popular that, no doubt to corporate dismay, its name is commonly used for any generic sealable, re-usable plastic food container — without which we can hardly imagine leftovers.

The Bain-Marie

The bain-marie, or double boiler, is a nifty contraption that takes the guesswork out of cooking temperamental (i.e., easily burned) substances like milk or chocolate. The traditional apparatus, with a pan suspended above a pot of boiling water, was first developed by medieval alchemists who needed a gentle way to melt their precious materials. Electric bain-maries permit temperature control, and innovations of the past decade, like the Roner — a thermal circulator invented by two Catalan chefs, Joan Roca and Nora Caner — allows cooking at absolutely uniform and precisely calculated temperatures. Among other things, Roners and similar appliances are essential in sous-vide cookery.

The Weber Grill

The original kettle grill, the Weber was the brainchild of an amateur backyard barbecuer named George Stephen, Sr., who sought a way to control the fire over which he loved to cook. He worked for a Chicago metalworks, Weber Brothers, whose business included joining metal spheres together to make buoys for the Great Lakes. Where others saw buoys, he saw grills; he fashioned one of the former into something very like the now-ubiquitous Weber in 1952, and it worked well enough that he talked the company (which he later bought) into manufacturing them. Cookouts haven't been the same since.

Teflon

DuPont scientist Roy Plunkett was experimenting with frozen gasses related to Freon in 1938 when he discovered that one of his samples had congealed into a white, waxy substance so slippery that almost nothing would stick to it. Manhattan Project scientists, developing the atomic bomb, found uses for it. DuPont began manufacturing cooking products coated with the substance, which it dubbed Teflon, after World War II. Today, it's a rare kitchen that doesn't boast at least a couple of non-stick pans, Teflon or otherwise.

The Blender

In 1922, electric company owner Stephen Poplawski patented a contraption for making milkshakes and malts — a canister with small blades at the bottom, driven by an electric motor — and later came up with a variation that could purée fruits and vegetables. Engineer Frederick Osius improved on Poplawski's design and, with backing from popular bandleader Fred Waring, started selling the Waring Blender. In 1946, one John Oster, who had bought Poplawski's company, introduced the Osterizer, which became an essential piece of equipment for every modern kitchen. Many other brands (including the protean Vita-Mix) followed, and even the home food processor hasn't wholly replaced the blender in our culinary arsenals.

The Stand Mixer

Hobart engineer Herbert Johnson designed an 80-quart electric stand mixer for commercial bakeries in 1908. Eleven years later, Hobart formed their KitchenAid division to market smaller units to restaurateurs though they weighed 65 pounds and cost $189.50 — nearly as much as a Model T Ford at the time. Still smaller home mixers, which first went on sale in 1936, are standard equipment for anyone who bakes regularly.

The Food Processor

The main difference between a blender and a food processor is that the latter has interchangeable blades so it can perform a myriad of tasks beyond just blending and puréeing. The first such machine was the Robot Coupe, designed in 1960 for use in professional kitchens by restaurant equipment salesman Pierre Verdun. A home version, Le Magimix, appeared in 1972, and the next year, inventor Carl Sontheimer brought it to the United States and rechristened it the Cuisinart. It was slow catching on with home cooks, until it was endorsed by food celebrities like James Beard and Julia Child. These days, it's hard to imagine a kitchen without a Cuisinart or one of its clones.

The Squeeze Bottle

The squeezable ketchup bottle was created by Stanley Mason, a professional inventor who also holds patents on such essentials of modern life as underwire bras, disposable diapers, and peel-apart Band-Aid wrappers (his ill-conceived attempt to package single servings of sardines in plastic wrappers was less well received). A fixture in diners for decades, the bottle was first manufactured for home use by Heinz in 1983 and has become a familiar site in many a cupboard and refrigerator door. It has also found a whole new professional life in recent years as a means of adding trendy little squiggles of balsamic glaze, chipotle mayonnaise, and other frou-frou to restaurant plates.

Paper Towels

Sure, you could drain bacon on yesterday's papers and dry rinsed herbs between layers of kitchen towel and blot up that spilled tartar sauce from the linoleum with a sponge or three — but why would you? To do all that stuff and much more (and a lot more neatly, too), paper towels were originally invented by the Scott Paper Company in 1907 as disposable and thus sanitary restroom hand towels (they had earlier come up with the idea of tissue on rolls and toilet paper) and first sold for kitchen use in the 1930s. We can't imagine kitchen life without them.

"Cooking" with Liquid Nitrogen

First successfully converted into liquid form by Polish physicists in 1883, nitrogen found immediate culinary use as a means of freezing in Victorian ice cream parlors. Over a century later, it has become famous for its use in the kitchen at El Bulli in Spain and other high-end contemporary restaurants and for dozens of appearances on Top Chef. Liquid nitrogen's ability to dramatically alter the form of everything from olives to egg yolks to foie gras makes it one of the flashiest tools of the culinary avant-garde.

The Pull-Tab

Talk about important. How did we ever open our Dr Pepper cans without these things? Based on a pull-top for bottles, the first example was tested in 1962 but showed up on Schlitz cans in 1963, and the concept soon found its way into the everyday lives of anyone who even sipped soda or suds — along the way obviating the need for that triangular-headed instrument known irreverently as the church key. In 1975, a designer for Reynolds Metals came up with an environmentally friendly version of the pull-tab that stayed attached to the can it opened. In recent years, pull-tabs have shown up not just on beverage cans but on containers holding soup, beans, nuts, and Fancy Feast to name a few.