The Economical Origin Of The Classic Tuna Salad Sandwich

The tuna salad sandwich was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a salad before it was a sandwich. Tuna salad is a newer rendition of a centuries-old culinary trend of minced meat salads. These didn't become popular until the invention of mayonnaise, credited to a French chef who devised the condiment in 1756 for a feast to celebrate a French victory during the Seven Years' War.

Though tuna was popular among other cultures long before — particularly along the Mediterranean — it was not really consumed in the States until the 20th century. But the taste for tuna salad has always coincided with a push for the economical, emphasizing that distaste can reverse itself through times of scarcity and effective advertising.

Though the ebb and flow of tuna salad's popularity have been as cyclical as the tides from which tuna itself is fished, the taste for it remains a fundamentally American fixture of equal parts nostalgia and convenience. Today the tuna salad sandwich's brief but fraught history persists with the principle of economy — a traditional recipe can be made and enjoyed in minutes.

Meat salads are a thrifty culinary tradition

Two separate origin tales have a claim to the heritage of tuna salad. On the one hand, leftovers from meat-based dishes have inherently been repurposed since time immemorial to prevent anything from going to waste in a world before refrigeration. On the other hand, the phenomenon of bound salads has a history rooted in the culinary traditions of 19th century German immigrants who cooked up chicken and potatoes with the express intention of turning them immediately into respective bound salads as main courses.

Whether served intentionally for dinner as a primary dish or as a lunch of creatively comprised leftovers the next day, meat and fish-based salads mixed with mayonnaise and relish provided a tasty and convenient catchall for surplus ingredients. These were often served on a bed of lettuce, making these dishes salads in more than one sense of the word.

While fish salads were part of this culinary phenomenon, they were not initially made from tuna. Salmon, trout, and whitefish (like cod and mackerel) were more common seafood staples of choice during the 19th century. Tuna wasn't on the menu yet because most people had never heard of it.

Women's freedoms inspired a new restaurant salad

With the rise of the first department stores during the 19th century, it became socially acceptable for women to make more appearances in public, but it was still considered unseemly for a respectable woman to eat at a restaurant without a male chaperone.

Rather than simply inviting women into the male space, new establishments emerged, catering especially — even exclusively — to women. Since women were barred from typical saloons, these women's spaces became known as ice cream saloons, many of which were exceedingly luxurious. Due to their domestic decor, these female-friendly spaces were more colloquially known as ice cream parlors, serving lighter fare that was marketed as "feminine" — besides ice cream, there were often salads on the menu. Too refined to use leftovers to construct chicken, fish, and shellfish salads, these restaurants cooked up meat and fish to create these main course meals from scratch.

As more women entered the workforce throughout the 20th century, new dining venues evolved to accommodate feminine appetites, and fish salads remained a fixture on the menu. But lunch breaks for working women weren't the same as a leisurely ladies' afternoon meal at an upscale restaurant. Lunch counters, alternatively, became a popular place for busy women to grab a quick midday meal. To speed up the dining process even further, the salads advertised primarily to female patrons were served between two slices of bread, evolving into salad sandwiches that could also be ordered to go.

Tuna becomes an unexpected replacement fish

Prior to the turn of the 20th century, tuna was a species of fish regarded in the U.S. as unsuitable for human consumption. Perhaps due to its piquant, fishy flavor, tuna didn't catch on with American tastebuds through any merit of its own. Before the 1900s, if tuna was caught at all, it was used as bait, turned into pet food, or caught for sport and simply thrown away.

Salmon and sardines were the fish of choice that Americans consumed most regularly in the 1800s, but this changed due to struggles within the fishing industry that culminated in 1903. This was the year of a debilitating sardine fishing season, the consequence of bad seafaring conditions combined with general overfishing. This sardine deficiency prompted executives to pivot their fishing vessels and experiment with other types of catch. The Southern California Fish Company found the most success with albacore tuna, which was then abundant in Pacific waters.

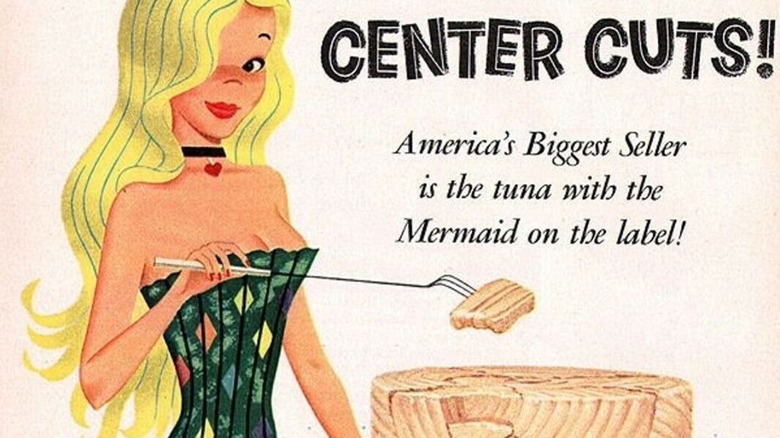

A combination of improved fishing and preserving technology made it easier to catch large tuna and remove the oil that gave tuna its previously unpalatable fishiness. These innovations helped to reintroduce tuna as a viable source of protein for American consumers, but it took a great deal of coercion to sell something to a market that still largely considered tuna inedible. It was a long and widespread advertising campaign that truly convinced Americans they could eat — and even enjoy — tuna.

Convincing Americans to love tuna

Tuna was most successfully pitched to the masses through a point of comparison. Albacore tuna was likened to white chicken meat, earning it the nickname "chicken of the sea" among the fishermen hunting for it. What started as a joke evolved into one of the leading tuna brands, which eventually took the name of their company.

Though it took a few years to catch on, this just-like-chicken comparison wasn't an advertising mistruth — tuna proved to have a similar mild flavor to chicken, making it a versatile ingredient with limitless potential. Largely due to such persistent marketing efforts, tuna became an easy substitute for the chicken and fish salads that were already rising in popularity in restaurants across the country, with the added convenience of being ready to serve straight from the can.

"Tuna Salad Popular," a 1913 edition of the Christian Science Monitor (via Food Timeline) reported, "In California the tuna is being introduced generally in the best restaurants, not only because it is new, but because people are beginning to value it for what it is." From this point on, people valued canned tuna's mild flavor and convenient preparation equally, though the fish found its first source of widespread demand a couple of years later when it became an important source of readily available protein for U.S. troops in the trenches of WWI.

America's new favorite seafood

In the decades proceeding tuna's introduction to the American diet, it quickly surpassed all other fish forms to become one of the most ubiquitous seafoods in the States. By the 1930s, the demand for tuna was so high it followed the earlier precedent of sardines, resulting in overfishing in California's waters, which prompted fishermen to venture further south to seek tuna from the shores of Mexico and South America.

Though scant tuna populations in the Pacific were just one of many forms of food scarcity that defined this era, the continued hunt for tuna in more southern waters kept canned tuna readily available in grocery stores. As a result, tuna sandwiches were consumed across America as cheap but fortifying meals, a significant protein source that got many families through the Depression.

From 1950 to 2000 tuna (usually canned) was the most popular seafood in the U.S., and tuna salad was a favored comfort and convenience staple for Americans from all walks of life. One of Julia Child's favorite lunches, the tuna salad sandwich has come to be enjoyed equally among both popular and epicurean palates.

Historic alterations to tuna salad

From the start, most tuna fishermen in California were Japanese immigrants, and their innovative fishing methods enabled the industry to thrive. But when the bombing of Pearl Harbor amplified anti-Japanese sentiment, these fishermen were among the Japanese families that were isolated in internment camps. This disrupted the tuna industry nearly as much as the lives of its workers, but America's taste for tuna did not subside as a result.

By the time the U.S. had cycled into the postwar economic boom of the 1950s, tuna salad took on new forms — the era's gelatin craze meant that tuna salad found its way into Jell-O molds just as often as sandwiches. While most of the original Japanese tuna fishermen did not return to the trade after the war, tuna salad migrated to Japan, becoming a filling for onigiri and a new kind of sandwich served on shokupan bread with Kewpie mayonnaise, a savory outcome from an unsavory moment in history.

In the 1960s, tuna salad sandwiches got a further American makeover via a South Carolina kitchen mishap, when a bowl of tuna salad got knocked onto a grilled cheese sandwich. The cook who witnessed this accident found the unintended combination proved to be unexpectedly harmonious. Thus the tuna melt was born, giving the tuna salad sandwich a new lease on life as a hot sandwich and ensuring it would continue to remain a fixture in restaurants, diners, and lunch counters ever after.