Goodbye To The Extraordinary George Lang

"Dear Colman," read the fax I got from George Lang one morning almost 20 years ago in my office in Santa Monica, after I'd had to revise my itinerary for a planned trip to Europe. "1. I did change my schedule to be able to meet you in Budapest. 2. I am switching a few dozen appointments in a half a dozen cities to be able to be with you on Monday the 19th. 3. If you change it again a fourth-century curse of the ancient Hungarians will be invoked against you and its results are not faxable. Therefore: I hope to see you between 9:30 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. at Gundel. Perhaps you could come through the employees' entrance..."

Gundel, which opened in Budapest's City Park in 1910, was once the most famous restaurant in Central Europe, the so-called Maxim's of the East. Until Hungary's communist government nationalized it in 1949, Gundel welcomed — as Joseph Wechsberg put it in Blue Trout and Black Truffles — "every tourist, painter, banker, singer, diplomat, king, ex-king, musician, politician, and... restaurateur on the Continent, and many from elsewhere."

The communists, of course, botched it, as they botched almost everything, and eventually closed the place down in 1972, reopening it eight years later in a stripped-down, "modernized" version. I visited it in the late 1980s, and it was pretty grim. The famously glittering old Gundel interior was now dark and junky-looking, with room dividers of cheap paneling and rows of unset tables stretching into the gloom.

I had lunch on the terrace, beneath a yellow Camel cigarette umbrella, next to a white plastic latticework planter, eating fish of some description in a spongy egg batter topped with frozen peas and a lumpy cream sauce that had, I scribbled in my notebook at the time, the consistency of library paste mixed with canned applesauce. It took a good deal of imagination to imagine Gundel as Wechsberg must have known it.

George Lang saved Gundel. It was hardly his only accomplishment, however. Born in 1924 in Székesfehérvár, about 40 miles southwest of Budapest, he studied violin as a child and moved to the U.S. immediately after World War II — both his parents had died at Auschwitz, and he was himself imprisoned in a Hungarian labor camp and nearly executed — to become a concert musician. He won a scholarship to Tanglewood and played briefly with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra — but, he once told me, he made the mistake of going to hear Jascha Heifetz play one evening, and came away realizing that he would never be a truly great violinist.

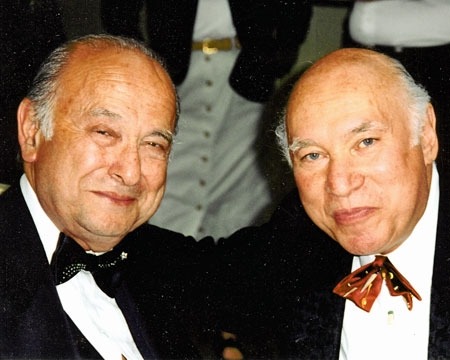

Restaurant Associates. He opened the Tower Suite atop the Time-Life Building for RA, and managed the Four Seasons for several years before leaving to launch his own restaurant consulting business — one of the first such enterprises, if not the first, anywhere — in 1970. (Photo courtesy Gerry Dawes)

He helped create or remake scores of establishments for various clients over the years, and in 1975 himself took over the venerable Café des Artistes on New York's Upper West Side, revivifying it and turning it into a popular destination for tourists and locals alike. (It closed in 2009 and has reopened as an Italian restaurant.) Along the way, he found time to write the definitive Cuisine of Hungary and a memoir called (this must have seemed like a good idea at the time) Nobody Knows the Truffles I've Seen, and several other books.

That would have been an impressive enough career right there. But, though Lang never said this in so many words, at least not to me, I'd wager that, of all the many contributions he made to dining in the 20th century, he was proudest of his revival — reinvention is not too strong a word — of Gundel.

After the demise of Hungary's communist regime in 1990, businessman Ronald Lauder, a former U.S. ambassador to Austria and son of the Budapest-born cosmetics queen Estée Lauder, bought Gundel from the Hungarian government, for an estimated $18 million, in partnership with Lang. In an astonishingly short time — about seven months — Lang completely transformed the place, restoring it to what I suspect was its old glory and then some.

Adam Tihany redesigned the 3,500-square-foot dining room, giving it glossy fruitwood paneling, deep blue upholstery, and dazzling chandeliers whose light seemed to dance through the air in time with the Gypsy orchestra Lang installed. Decorative details sparkled, and the interior somehow seemed soaked in the past but brightly contemporary at the same time. I remember thinking, when I first set foot in the place (albeit through the employees' entrance), that Gundel felt electric, larger-than-life, almost fantastical. As I discovered at lunch there that day, the food was wonderful, too.

My first meal at Gundel (I've had a dozen or more since, over the years) began with fresh carp in aspic garnished with exquisite little dumplings of pike-perch, a superb "rich man's purse" of strudel dough stuffed with ground chicken in paprika sauce, and a delicious "tycoon's gulyás," or goulasch, made with cubes of beef tenderloin in a sauce flavored with garlic, paprika, and caraway seeds. Sitting there in these opulent surroundings eating this perfectly prepared food, both delicious and slightly exotic, served with considerable grace by a formally garbed multlingual staff, I felt like I was in the most glamorous restaurant on earth. Gundel was — and as far as I know still is (I was last there in 2005) — really something special.

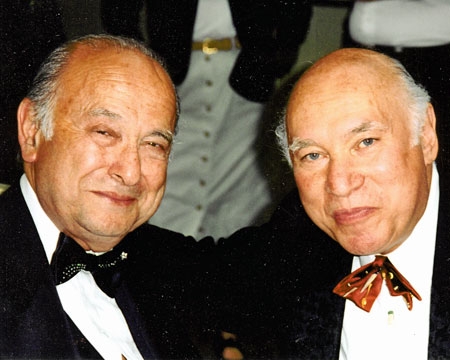

(Photo courtesy of Jenifer Harvey Lang)

That wife, his third, was Jenifer Harvey Lang, author of the last two editions of the Larousse Gastronomique, among other books, and manager of Café des Artistes until its demise. It was she who announced the sad news yesterday that her husband — who was being treated for Alzheimer's disease — had passed away on Tuesday.