Ferran Adrià Says Goodbye: The Last Day Of El Bulli

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

July 30, 2011. It was a warm, humid morning at Cala Montjoi. There was a scent of pine and seawater in the air, but the sun wasn't having much success in its attempts to nudge aside the clouds.

El Bulli — the restaurant that has brought the gastronomic world to this little cove about 15 miles south of the French border in Spain's Costa Brava region — would exist as a temple of avant-garde haute cuisine. (The elBullifoundation [sic] that will replace it, opening in 2014, will definitely serve food of some kind, though exactly what and how frequently has not yet been determined.)

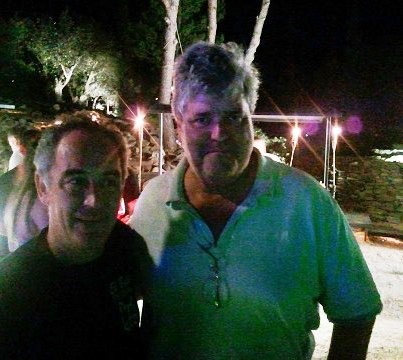

Outside El Bulli, often hailed as "the world's most famous restaurant" and almost certainly the world's most influential, a mob of journalists, photographers, and videographers — some, making an official documentary, sported black T-shirts reading "Last Waltz El Bulli" — milled around the big, round gravel parking lot waiting for the official program to begin. (The only Americans among them, besides myself, appeared to be Jeffrey Steingarten of Vogue and Time stringer Lisa Abend, author of a new book about El Bulli's stagiares, or interns.) (Pictured left, the author with Ferran, about halfway through the after-dinner party)

Last year, when I first asked Ferran Adrià what would happen on the closing night of El Bulli, he replied, "There will be nothing special. We'll serve dinner as we would any other night, and then go home." Ha. If there's one thing I've learned in all the time I've spent with the legendary Catalan chef over the past three years, working on and then promoting my biography of him, it's that nothing he says about the future ever just sits there and behaves. His thinking constantly evolves; that is, new ideas and inspirations fill his head as circumstances change, or his view of them adjusts. Thus he has decided to put on a bit of a show.

Albert Adrià (center) shoots back at the photographers.

A dais has been set up in a shaded corner of the parking lot, and the names on the placards in front of each chair testify to the seriousness of the event: Ferran and his longtime business partner and front-of-the-house manager, Juli Soler, are there of course. The other names are Joan Roca (El Celler de Can Roca, Girona), Andoni Aduriz (Mugaritz, outside San Sebastian), Massimo Bottura (Hosteria Francescana, Modena), Grant Achatz (Alinea and Next, Chicago), José Andrés (too many restaurants, in Washington, D.C., Las Vegas, and Los Angeles, to count), and René Redzepi (Noma, Copenhagen). All these chefs once worked in the El Bulli kitchen, and all of them openly credit Ferran with inspiring them. (Somehow, there was neither a chair nor a placard for Ferran's brother and career-long collaborator, Albert, who is now the proprietor of the Bulli-esque Barcelona tapas bar Tickets La Vida Tapa, but a place was found for him, too.)

Behind this illustrious crew — who accounted for 15 Michelin stars between them, according to my calculations — sat a second line of El Bulli veterans, including Kristian Lutaud (who was co-chef with Ferran in late 1984 and '85 and who now consults for various hotels and restaurants around Spain), Xavier Sagristà (who Ferran has called one of his most important creative collaborators, and who now cooks at his own Mas Pau near Figueres), Carles Abellan (proprietor of Comerç 24 and Tapas 24 in Barcelona), and Albert Raurich (Dos Palillos in Barcelona and Berlin), as well as chefs Eduard Bosch, Marc Cuspinera, Marc Puig-Pey, and Rafa Morales. (Two El Bulli executive chefs from earlier years — Jean-Louis Neichel, who won the restaurant its first Michelin star, and Jean-Paul Vinay, who became the youngest two-star chef in Europe when he earned it a second one — were absent, though whether because of bad blood or previous commitments was not apparent.) A third rank, perched on a rock above the others, was composed of the heart of the current El Bulli staff, among them chefs Oriol Castro, Eduard Xatruch, Eugeni de Diego, and Mateu Casañas.

The panel, left to right: Achatz, Andrés, Redzepi, Ferran, Albert, Roca, Bottura, Aduriz.

Everyone said a few words. Aduriz paid tribute to the values instilled in him at El Bulli and said bluntly, "I would not do what I do at Mugaritz if I had not worked here first." Bottura, who spoke in what he called "Italo-Español," noted that he had only worked at El Bulli for three months but that was enough to make him feel like part of the family, adding that he had done his apprenticeship here alongside René Redzepi, and that they used to talk all the time until he realized that there were other paths to cooking than the traditional ones.

Redzepi himself, speaking in English translated by José Andrés, said that his El Bulli story began a year before he came to work there. "I was working in France," he said. "I had been trained classically French.... I was going to travel the world to learn more French cuisine and go back to Denmark and created my own version of French cuisine. And then I read about this restaurant..." He easily got a reservation in the pre-Bulli-hysteria days. "And I had a meal that just simply planted a new seed in my head," he continued, "a seed that today has grown a lot, which is my restaurant." He concluded with a tribute to all the effort that has gone into El Bulli. "This place has been created by so much hard work," he said, "and I would like to thank everybody here for helping free my imagination."

Achatz, again with Andrés translating, told the audience how he came to El Bulli as a 25-year-old sous-chef at The French Laundry, thinking he knew all about cooking and when he walked into the kitchen for the first time "felt like I was on a different planet." Food in America at that time, he said, was stale, and being here lit a fire for him, giving him courage. "That confidence to express," he concluded, "to accept challenge and risk, has been very important in my life."

After the program, Ferran and the other chefs made themselves available for an hour or so for what he called, in English, "one on one" — i.e., interviews. Around two, bottles of cava were uncorked on the terrace and trays of delicious little bites were passed — razor clams, good ham on crispy but ephemeral little "air baguettes," barely-cooked shrimp, little liquid croquettes of hare... The staff was in high spirits. There was a sense of giddiness, silliness in the air. I was reminded of a college graduation, with its combination of joy, relief, uncertainty, and premature nostalgia. At one point, I looked over the wall down towards the cove and noticed a scattering of bathers gaping, some taking photos, some walking up the path to the restaurant to try to get a closer look at what was going on.

By three, most of the press corps had packed up, and anyway it was time for everyone to get to work. There was still one more dinner to be served at El Bulli.

At seven in the evening, the first guests — a glamorous-looking collection of Ferran's friends (no journalists allowed) — began arriving. The real glamour, though, some might have said, was in the kitchen: In addition to the usual crew — Ferran's longtime numbers two and three, Castro ("one of the five best chefs in the world," Ferran once called him) and Xatruch, et al. — and the full complement of unpaid stagiares, all the star chefs who had come for the day had figuratively rolled up their sleeves and were literally helping to cook. Surely no diners in the world have ever before been ministered to by so many culinary luminaries. (Who cooked your dinner tonight? Oh, just Adrià, Redzepi, Achatz, Roca, Andrés, Bottura, Aduriz, Abellan...) As (José) Andrés put it, "It was incredible. We had a full team working, all of us together, and another 16 chefs in reserve." Andrés had even put his three charming young daughters, Ines, Carlotta, and Lucia, all wearing chefs' whites, to work.

Ferran takes out the last order to be served at El Bulli.

The 50-course menu was a kind of retrospective of some of the restaurant's most celebrated creations, including the hot-and-cold Gin Fizz, Spherical Olives, Mimetic Peanuts, Gorgonzola Balloon, Olive Oil Chip, Smoke Foam, Veal Marrow with Caviar, Curry Chicken (the famous "deconstruction" in which the curry flavor is solid and the chicken is liquid), "Gazpacho" and "Ajo Blanco", and Hare Loin in Its Own Blood. Ferran started the evening expediting orders as he has done for decades, then stepped aside to let other chefs take over. About halfway through the service, he announced, "The last ticket [order] at El Bulli has just arrived from the dining room." A couple of hours later, he admitted that he had officially ordered the last dish that would ever be served at the restaurant called El Bulli — nothing spherified or liquid-nitrogened, but Ferran's variations on a classic peach Melba, based on a recipe by Escoffier (Andrés had earlier gifted Ferran with a first edition of the great French chef's Guide Culinaire, signed by Escoffier himself). He called for a moment of silence, then told the crew: "All this isn't for the people outside, it's for you, who have worked so hard."

When the peach Melba was ready, he strode to the dessert station, picked up the tray, and carried it out to the servers. The kitchen erupted in whoops and applause — an ovation, accompanied by much hugging and leaping about, that went on for at least two minutes. It was hardly, in other words, a solemn occasion; the feeling was more like what you'd expect in the locker room after your team has won the World Series.

The stagiares hurled their towels into the air — their traditional end-of-season ritual — and then Ferran and everybody else trooped outside. "A la fiesta!" Ferran shouted — which might be loosely translated as "Party time!"

Smoked salmon and anchovies at the party.

The parking lot, which had been an outdoor lecture hall and photo studio in the morning had been transformed into a disco-cum-tapas bar. An arc of stands curved around half the lot: two bars; booths dispensing Joselito jamón ibérico (arguably Spain's best ham), barely cooked fresh shrimp and crayfish, assorted cured seafood (anchovies, smoked salmon, oil-packed tuna belly), pinxos (skewers) of marinated chicken, and various desserts; and a DJ station, perched a little up the hill behind a battery of speakers and multi-colored strobe lights. At one end of the area was an immense bulli, or French bulldog (the restaurant was named, almost half a century ago, for the breed — a favorite of the founder, the Slovakian-born Marketta Schilling). It looked like a butter sculpture, but had in fact been made of nougat, by the renowned Barcelona pastry chef Christian Escribà, whom Ferran has described as his best friend. Around the dog's neck was a garland of multicolored sugar flowers, the work of Escribà's frequent collaborator, the Brazilian sugar sculptor Patricia Schmidt.

In the days before El Bulli became an international gastronomic legend, Ferran, like most of the kitchen crew, was known as something of a party animal. I saw this side of him for the first time on this occasion. Freed, at least temporarily, from the need for his characteristic professional rigor, he changed into a black El Bulli T-shirt — on the back was a new El Bulli logo, a bulldog heading down the road with a hobo bag on a stick over his shoulder — and a pair of board shorts and flip-flops; grabbed a goblet of gin-and-tonic (the drink of Spanish chefs these days); and headed for the dance floor, where, it must be reported, he was seen to shake his booty.

Sant Pau in Sant Pol de Mar; the Barcelona chef and restaurateur Fermi Puig (Drolma and Petit Comité), who convinced Ferran to take a temporary job at El Bulli in the first place back in 1983; Toni Massenés, director of Ferran's "other" foundation, the science-oriented Alícia Foundation; Italian tool distributor and food photographer Bob Noto, who holds the distinction of having eaten at El Bulli more than any other customer; and Barcelona journalists Xavier Agulló (whose wedding Ferran once catered) and Pau Arenós, who coined the term "technoemotional cuisine" to describe the cooking style of Ferran and his professional colleagues. (Pictured left, Pastry master Christian Escribà with his nougat bulli)

Ferran dancing.

The fiesta lasted until about four in the morning. As a nightcap, Ferran revealed why he was wearing board shorts, and led a troop of his friends down to the beach and plunged with them into the warm Mediterranean waters.

This is the way "the world's greatest restaurant" ends, then: Not with a whimper but with a bang-up bash.