The Daily Meal Hall Of Fame: Auguste Escoffier

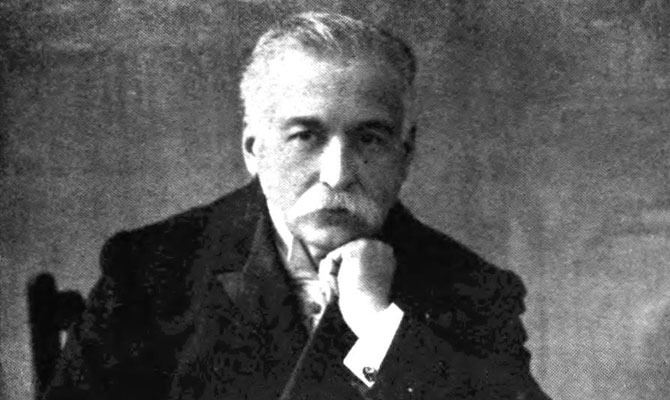

With the help of The Daily Meal Council, we have selected ten key figures in the history of food to honor this year in our Hall of Fame. Here, Council member Anne Willan, author, culinary historian, and founder of La Varenne Cooking School in Paris, explains why French chef Auguste Escoffier belongs on the roster.

It's amazing, really, that the reputation of Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846—1935) still resounds in today's kitchens. His masterwork, Le Guide Culinaire, was published more than 100 years ago, in 1902, yet you can still find it on the bookshelves of today's chefs.

It was never an easy read. Le Guide is a dense catalog of more than 5,000 recipes boiled down to a kind of shorthand that only a trained cook could understand — "a tool rather than a book," as Escoffier himself described it.

Escoffier established building blocks — basic sauces, stocks, and garnishes — that he built into the great dishes for which he created his famous recipes. Take his legendary tournedos Rossini, his entry for which, in the space of five lines, uses two technical terms (sauter and déglacer), two basic preparations (meat glaze and demi-glace sauce) that take hours of advance preparation, plus a rare ingredient (fresh foie gras).

To the professional chefs of the time, who knew the terms intimately and had basic sauces ready at hand, Le Guide was the perfect quick guide, the "constant companion" that Escoffier had hoped it would become. And so it remained in top kitchens throughout Europe and America until the late 1960s, when its outmoded style was swept away by Nouvelle Cuisine.[pullquote:left]

In some unexpected ways, though, we are now back to the principles of Escoffier. Now, as then, invention is the name of the game, though Escoffier would have mistrusted the current manipulation of ingredients. "Faites simple, things should taste of what they are," he declared. He was a master menu planner. He wrote a whole book, Le Livre des Menus (1912), defining the balance of taste, color, texture, and, indeed, drama, of a well-planned meal. He favored the same ten- or twelve-course menus that are popular today as tasting menus. However, the muddle of trendy serve-yourself small plates would have shocked him profoundly. Likewise, he would have chuckled at the wordy descriptions on modern menus. Instead of listing every ingredient and their provenance, he named dishes for the rich and famous who flocked to his restaurants — guests such as the opera singer Dame Nellie Melba (pêches Melba and Melba toast) or the Rothschilds (soufflé Rothschild, flecked with gold leaf) — thus combining brevity with good public relations.

Born in an obscure village on the French Riviera, Escoffier apprenticed in the kitchen of an uncle's restaurant in Nice and toiled in other kitchens as a young man. His big break did not come until he was 34, when he was summoned in an emergency by the legendary hotelier César Ritz to head the kitchens of the Grand Hotel in Monte Carlo. With Ritz helping to lure a glitterati clientele, Escoffier went on to open half a dozen top hotels and restaurants in London, Paris, Cannes, and Lucerne. When the team took over the Savoy Hotel in London, guests such as the Vanderbilts, the Rothschilds, the Morgans, and the rest of the beau monde followed.

There was a darker side to all this splendor. Escoffier headed a staff of 300 or more, and the conditions in which they worked were grueling. Fourteen-hour days were routine. A shy, sensitive man himself, he sought to root out the kitchen violence which was rife in these stressful conditions. He did this in part by establishing the brigade de cuisine hierarchy, from chef de cuisine on down, which is still used — or consciously departed from — in large kitchens today.

Escoffier's greatest and most lasting achievement, though, was probably to change the image of cooking from a grubby, manual trade to a respected profession. The chefs in his entourage basked in his celebrity spotlight, and with them the wider world of working cooks earned new respect.