10 Things You Didn't Know About MSG

10 Things You Didn’t Know About MSG

Monosodium glutamate, more commonly known as MSG, is a form of one of the most abundant naturally occurring non-essential amino acids on earth, glutamic acid. It's also one of the most misunderstood food products known to man. Read on to learn what MSG actually is, along with 10 things you most likely don't know about this flavor enhancer that seriously gets no respect.

It’s Naturally Occurring in Lots of Foods

Glutamic acid, to which MSG is chemically identical, is a naturally occurring amino acid that's found in many, many different foods and in the human body (we produce 40 grams of it ourselves every day; human milk contains 10 times as much glutamic acid as cow's milk). Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese contains more free glutamate than any other natural food on the planet (1,200 milligrams per 100 grams), and Marmite and Vegemite (1,750 milligrams per 100 grams) contain more than any other manufactured food. Other foods that are high in natural glutamates are tomatoes, cured meats, mushrooms, soy sauce, fish sauce, Worcestershire sauce, and asparagus.

It Contains Only About One-Third the Sodium of Table Salt

MSG is 12 percent sodium, while table salt is 39 percent. For those looking to reduce their sodium intake, up to 40 percent of the salt used in food can be replaced by MSG with no perceived reduction of saltiness.

It Proved the Existence of Umami

Because MSG is essentially pure umami, its invention proved scientifically that the flavor category known as umami does exist. And not only that: By adding pure MSG to a dish, the umami factor can be vastly amplified.

One Man Started the Myth That MSG Is Bad for You

If you still buy into the myth that MSG is bad for you, you should probably consider the source: a lighthearted April 1968 article in the New England Journal of Medicine by one Dr. Ho Man Kwok. "I have experienced a strange syndrome whenever I have eaten out in a Chinese restaurant, especially one that served northern Chinese food," he wrote. "The syndrome, which usually begins 15 to 20 minutes after I have eaten the first dish, lasts for about two hours, without hangover effect. The most prominent symptoms are numbness at the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back, general weakness and palpitations..." The article wasn't specifically about MSG, but it was enough to kick off one of the great food scares of the twentieth century.

Studies Have Shown that ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’ Doesn’t Exist

This pseudo-disease, which came to be known as Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, flew in the face of science. It became an obsession in the 1980s, even though it's been consistently and thoroughly debunked. Every single official governmental and academic body that's ever studied MSG has given it a clean bill of health (the FDA has done so three times, in 1958, 1991, and 1998). If you feel crummy after eating Chinese food, blame it on the salt, fat, spice — or Tsingtao — but not the MSG.

Humans Can Metabolize Far More MSG Than Is Used in Food

According to the FDA, the average adult consumes about 13 grams of glutamate every day from the protein in food alone, and only .55 grams of MSG daily. In fact, in 1970, 11 adults were fed up to a whopping 147 grams of MSG daily for six weeks and none of them reported any adverse reactions.

It’s in a Lot More Food Than You May Realize

Just because the label doesn't explicitly say "monosodium glutamate" on it doesn't mean that it does not contain glutamates. Hydrolyzed vegetable protein, autolyzed yeast extract, soy extracts, protein isolates, and any variation thereof also indicate the presence of the same compound as MSG. Take a look at a bag of Doritos; you'll find several glutamates on the ingredient panel.

It Can Appear on Some Labels as ‘Natural Flavor’

While foods that contain added MSG must list it on the ingredient panel, companies are not obligated to mention if a product contains ingredients with naturally occurring glutamic acid.

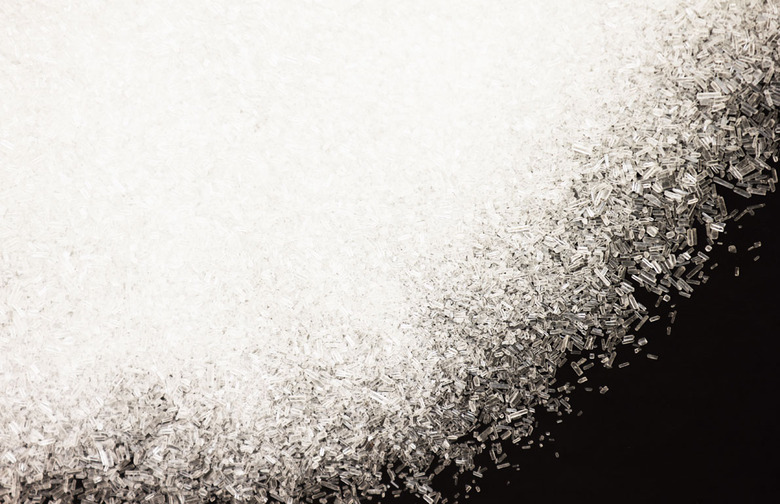

It’s Produced in a Fermentation Process Similar to That Used to Produce Vinegar

MSG can be synthesized with just about any food item that contains protein, but today it's made via bacterial fermentation. To produce MSG, bacteria cultured with ammonia and carbohydrates excretes amino acids into a "culture broth" from which L-glutamate is isolated. It's then stabilized with sodium, filtered, concentrated, acidified, and crystalized into a white, odorless powder.

You Can Buy It At the Supermarket

Plenty of home cooks across the world cook with MSG just like they would salt. In the United States, you'll usually find it as B&G Foods' Accent or Goya's Sazón; other brand names include Vetsin, Tasting Powder, and (of course) Ajinomoto.