The Surprising Drinking Habits Of Our Founding Fathers (Slideshow)

We're taught to think of Washington as the stoic, sober, wooden-toothed patriarch of our nation, but nothing could be further from the truth. Washington was known for tying one on with about four bottles of wine and dancing the night away. After his presidency, he opened one of the largest whiskey distilleries in the country at Mount Vernon that produced 11,000 gallons in 1799, the year he died.

John Adams

It's tough to say, but John Adams may have been the biggest drinker of the Sons of Liberty. He began every day with a draft of hard cider before breakfast. He drank three glasses of Madeira, a wine fortified with rum, every night before bed. During the bad old days under British taxation, Adams wrote to his wife, "I am getting nothing that I can drink, and I believe I shall be sick from this cause alone." He died at 90. Of old age.

Paul Revere

In 1775, Paul Revere famously rode out of Boston at midnight to warn his fellow patriots that British were planning a march on Lexington. But how did the word spread so fast and effectively? Because the people he was warning were at the many taverns at which he stopped on the way. According to his own journals, he may have had a few toots before the ride was over.

Thomas Jefferson

Our third president was, beyond being a master of statecraft, a very serious connoisseur of wine. During the Revolution, on diplomatic missions to France, he toured the vineyards of Bordeaux extensively. As president, he imported more than 20,000 bottles for his personal collection. Despite this, he insisted he was not a drunk: "...you are not to conclude I am a drinker. My measure is a perfectly sober one of 3 or 4 glasses at dinner, and not a drop at any other time. But as to those 3 or 4 glasses I am very fond."

Benjamin Franklin

Though he may have been the most temperate among his fellow Founders, Ben Franklin said, "Beer is living proof that God loves us and wants to see us happy." A brewer and distiller in his own right, he's also famous for coming up with The Drinker's Dictionary, over 200 euphemisms for getting tore up. Among my favorites: "Piss'd in the Brook," "Wamble Crop'd," and "Been too free with Sir John Strawberry."

Samuel Adams

Among the many lines on his resumé, one of them was brewer. Specifically, Sam Adams was a maltster in his father's brewery, the guy who made the malts that would eventually become beer. He was also a master politician, and is credited with organizing the Revolution from inside New England taverns by getting would-be Minute Men mad as hell over the high price of rum.

John Hancock

Before he ever put quill to parchment as the first signer of the Declaration of Independence, Hancock smuggled more booze into the colonies than most anyone else. He ended up being sued by the British government for unpaid taxes to the tune of about $7 million in today's money. This is how revolutions start, people.

Rum

No other commodity held as much of a place in the colonial economy than rum. Domestic rum was the backbone of the American economy before the Revolution, but when King George started screwing around with the importation of sugar cane molasses from the Caribbean, the price of rum went way up, and the OG patriots got pretty mad. We know what happened next.

Cider

The British love their beer, but things like barley and hops didn't grow very well in New England, so settlers there planted vast apple orchards from which they'd make a ubiquitous hard cider. Cider was so much a part of daily colonial life that an average man would've consumed a quart of it by breakfast.

Beer

Though more difficult to make in the colonies than it was back in England, beer remained a daily staple of most colonial Americans' lives for more than 200 years. Safer than water (because it was boiled, not because of the alcohol), there were even lower-alcohol versions, called Small Beer, brewed for children. Even the Puritans and Quakers who railed against alcohol consumption were actually only talking about distilled spirits. Beer and cider were just fine by them.

Whiskey

The rise of whiskey in America came on the tail of the first push westward in 1791. With beer and cider a scarce commodity outside the colonies, and rum having fallen out of favor before the Revolution due to its high cost, those settlers west of the Allegheny Mountains made due with home stills to produce a clear corn liquor, un-aged and resembling what we might call moonshine today. And, without a codified system of currency, most goods and services in rural areas were purchased with whiskey, not cash.

Taverns

Taverns weren't just a place where an early American would go to get a little tight. A colonial era tavern might also have served as post office, courthouse, wedding hall, and any number of other civic functions. It was also within the taverns that our Founding Fathers planned and staged the American Revolution. The Green Dragon, still serving rum punch in Boston's North End to this day, is known as the Headquarters of the Revolution.

The Liberty Riot

In 1768, British customs officials seized John Hancock's ship, The Liberty, in Boston Harbor, and accused him of smuggling about 100,000 gallons of wine and Madeira. Which was absolutely true. In response, thirsty American colonists dragged a customs ship out of the Harbor, paraded it through the streets, and turned it into a giant bonfire in the middle of Boston Common.

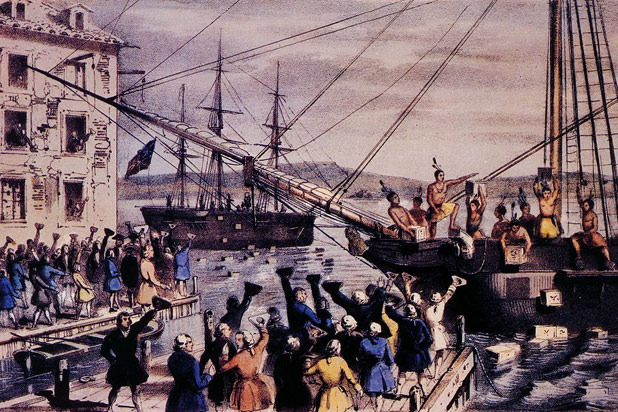

Boston Tea Party

Although ostensibly in response to the Tea Act of 1773, the Boston Tea Party was really a response to all the unfair taxes imposed by King George, most of which had to do with alcohol. The Molasses Act, the Sugar Act, and the Stamp Act all targeted the production, sale, import, and export of booze in the colonies, and the Americans weren't having it. Rather than destroy valuable rum in protest, however, colonial Bostonians — with Sam Adams as the ringleader — chose instead to drink the rum before launching the King's tea into Boston Harbor.