16 Hanukkah Foods Everyone Should Know

As a chef with Jewish heritage, I have always viewed the holidays through a culinary lens. In Judaism, food is as much an active part of the ritual of a celebration as prayer or attending religious services. The congregation around a dinner table enables us to reflect on the meaning of the observance of a holiday while simultaneously reinforcing our belonging to our faith through the consumption of symbolic foods.

This is no less true for Hanukkah, which, according to Reform Judaism, is one of the most widely observed holidays of the year. The eight-day celebration commemorates the historical triumph and reclamation of the Holy Temple by a band of Jewish rebels called the Maccabees over the Syrian-Greek army in 165 B.C.

Since the miracle of Hanukkah involved a single cruse of oil keeping the Temple's menorah alight for eight nights, the primary culinary symbol of this holiday is fried foods. A second lesser symbol is dairy dishes, which commemorate the heroism of Judith. Her story of feeding an Assyrian general copious quantities of salty cheese, causing him to drink himself into a stupor, and leading to his beheading made its way into Hanukkah celebrations by the 14th century, according to NPR.

All the dishes included in this list of Hanukkah foods fit into one or both categories. Some dishes are primarily consumed during Hanukkah festivities, while others appear during various Jewish holidays. Read on to learn about and discover the variations in these 16 traditional foods that make Jewish culinary heritage rich and diverse.

Latkes

Among the most quintessential fried foods consumed at Hanukkah is the latke. Eating latkes is almost a competitive sport, with pounds of the tuber getting shredded and fried in oil at the beginning of every Hanukkah celebration. Interestingly, the potato version of a latke we are familiar with today is a relatively recent addition to the Hanukkah celebration.

The earliest iterations of a latke were pancakes of various kinds made from locally found ingredients, like cheese or buckwheat. While the potato came from Peru to Europe via Spanish conquistadors in the mid-1500s, they did not become staples for consumption until the 18th century. At this point, Ashkenazi Jews of Europe converted their latke recipes to utilize the humble potato, asserting its superiority as the ingredient of choice.

Latkes today are as diverse as the Jewish diaspora, incorporating regionally available foods and adapting to individual palates. Many recipes utilize other ingredients, including sweet potatoes, zucchini, beets, and Brussels sprouts. And seasonings abound, from Tex-Mex spices to North African seasonings, like Ras El Hanout.

The key is to fry the latke in oil. And while you can top your latkes with sour cream, if you are keeping Kosher and expect meat to be served during the meal, stick to the classic garnish of homemade applesauce or compote. The sweetness of the applesauce helps cut the grease and balance out the flavors of classic potato latkes.

Sufganiyot

Sufganiyot, or jelly donuts, are another traditional fried food eaten at Hanukkah. Early variations of these pillowy treats originated in 15th-century Germany. These primitive donuts were often stuffed with savory fillings like cheese, mushrooms, and meat. It wasn't until the 16th century that jelly replaced these ingredients. During this time, the cost of sugar dropped dramatically, a by-product of the expansion of Caribbean slave-produced imports.

Jelly-filled donuts became particularly popular among Polish Jews, who carried their recipes and pastries to wherever they migrated. Once they arrived in Israel, these pastries became synonymous with the Israeli labor federation, the Histradut. By the 1920s, the Histrdut dubbed sufganiyot the official food of Hanukkah. The rest, as they say, is history.

Variations on these donuts have expanded to include other fillings, including chocolate, custards, and even a sweetened sesame paste known as halvah. And while classic sufganiyot were of Ashkenazi or Central and Eastern European origin, Sephardic iterations, like Moroccan Sfinj or Mexican Buñuelos, abound. Again, fidelity to frying the donuts is integral regardless of the precise origin, shape, or flavor they come in.

Gelt

In modern-day Hanukkah celebrations, gelt are known as little gold foil-encased waxy chocolate coins used to make bets during the annual game of dreidel. Its historical meaning is much more complex than a childhood game. The earliest gelt, or coins, pay homage to the first currency fashioned by the Maccabeans after reclaiming the Holy Temple.

Since the first celebrations of Hanukkah in Eastern European shtetls, the gifting of chocolate gelt during the holidays has continued to be associated with charitable giving and expressions of appreciation for services ranging from education to butchering meat. While the transition from actual currency to chocolate treats remains somewhat of a mystery, some scholars believe the tradition is a 20th-century Americanization of the ritual.

Regardless of how and when this shift occurred, Jewish children eagerly await their gift of gelt every Hanukkah. Though gourmet variations on gelt exist, a sense of tradition remains with the oddly synthetic-tasting iterations.

As my family fondly recalls, there is nostalgia in trying to peel the gold foil off of the melted chocolate-like sweet, even if it was not exactly what you would call flavorful. Sometimes, tradition dictates that you don't mess with even a not-so-good thing. Hanukkah gelt might just be one of those.

Brisket

Brisket is a delicacy served on many Jewish holidays ranging from Passover to Rosh Hashanah to Hanukkah. This kosher cut of beef stems from the front of the cow, an area enveloping the sternum and ribs. The cut can weigh anywhere from 10 to 20 pounds and is rife with dense muscle fibers and connective tissues. This makes it exquisitely well-suited for slow cooking. It also makes it a very cost-effective way to feed a large crowd.

Its affordability may have been one of the guiding factors to its popularity among the households of Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe. The need for producing hearty meals with few resources established a culinary tradition that has spanned numerous generations and countries.

To this day, including a rich, slow-cooked brisket is as celebratory as a bottle of champagne. Indeed, the recipe I most fondly recall is one produced by my mother-in-law that required over 24 hours of braising in copious quantities of onions, carrots, and stock. By the time the brisket made it to the Hanukkah dinner table, the aromas of beef put all of us in a reverent mood, befitting the impending ritual observations.

Kugel

Kugel, which means "sphere" in German, refers to a casserole-like dish that can be sweet or savory, made with or without dairy. The origins of this dish date back to 12th century Germany. At this time, a dumpling-like batter would be poured into a round cooking implement known as a kugelhopf. The kugelhopf would get lowered into the bubbling pot of Shabbat stew. Here, it would steam slowly and absorb the flavors of the meat and vegetables in the stew.

Somehow along the way, presumably in the late 19th and early 20th century when the home oven was invented, this Ashkenazi dumpling morphed into a baked dish that can be made from virtually any starch ranging from potatoes to rice to cornmeal, depending upon where it is prepared. The kugel of today is served at any gathering, including at Hanukkah, when it can symbolize dairy or oil, depending on the recipe.

The savory potato kugel resembles a latke. It can be made with or without dairy, accommodating Kosher and non-Kosher Jews. Our traditional kugel was made from egg noodles, eggs, ricotta cheese, sugar, and raisins. This recipe would accompany every meal we ate. It was light and fluffy, with a richness that could be enjoyed as a side dish, dessert, or a leftover breakfast the next day. It reheated beautifully, making it a family favorite to bring to potlucks or as a quick dish to throw together in a pinch.

Babka

Another Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish delicacy is the babka. This brioche-like pastry, almost a cross between bread and cake, originated among Polish and Ukrainian Jews. Similar recipes were seen all across Europe, but this one differed in that it often used oil rather than butter to keep it Kosher. Recipes today are more diverse, with many using butter and milk, but Kosher-friendly varieties can still be found.

The name babka is the Polish and Yiddish diminutive of the word baba, which is the word for grandmother. Some suggest this is a term of endearment referencing the pan in which it was baked, which gave it the shape of a woman's skirt. Others believe it references the shape of the grandmothers baking these sweet treats — sturdy and plump.

Regardless of which you prefer, this yeast-based dessert often appears at Shabbat and Jewish holidays, including Hanukkah. A unique feature of this treat is the swirl of filling that punctuates the center of the dough like a serpentine delight.

Classic babka is made with either chocolate or cinnamon raisin nut. Today, many bakeries create luxury babka with myriad fillings, including cheese, poppy seeds, and nuts. Some even add a boozy component with generous helpings of rum, making them distinctly celebratory.

Rugelach

Rugelach is often referenced as the miniature version of a babka, a tiny rolled pastry similar to a croissant stuffed with chocolate or cinnamon raisin nut filling. Even though similarities exist, it is more fitting to regard rugelach as its own entity. The term rugelach itself means "little twists." Like the babka, it is of Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish origin.

Unlike babka, early variations on rugelach were made using a rustic cottage or farmer's cheese with curds like less moist ricotta. Recipes today often feature cream cheese, yielding a dough that is infinitely more luscious than babka. The use of dairy in the dough is considered a nod to the story of Judith and her clever ruse to dispose of Assyrian general Holofernes. For this reason, it often makes an appearance during Hanukkah.

Like babka, modern iterations of rugelach can be found with seemingly endless fillings ranging from the classic to cheese, nuts, jam, and more. The ones I grew up eating were made with apricot preserves, raisins, ground walnuts, and copious quantities of cinnamon. They were chewy, moist, and delicious, especially suited to being eaten alongside a strong cup of coffee.

Challah

Challah is a braided yeast egg bread typically served at Shabbat or during various Jewish holidays. Its origin is decidedly not Jewish. The earliest iterations of a braided loaf made from potatoes and water emerged in Medieval Germany.

These berchisbrod, or berches for short, were adopted and adapted by Jews and brought to Eastern Europe. Here, they evolved, becoming denser and sweeter, with the addition of eggs and sugar, which became more readily available.

The first reference to the name challah was in a 15th-century text. The term itself has several meanings in Hebrew, ranging from "round" to "hollow," suggesting that the earliest iterations were less dense than today. Interestingly, the term is also used by Sephardic Jews to describe their kinds of flatbreads, like pita or chapati. The Ashkenazic version of this bread was baked every Friday for Shabbat and became ubiquitous among Jews in America.

Challah comes in myriad shapes, sizes, textures, and flavors. These are served at different holidays and times of the year. Each type symbolizes the manna or edible gifts from heaven that sustained the Israelites during their Exodus from Egypt.

Round loaves indicate continuity, ladder shapes suggest the need to ascend to greater heights, and braided ones with different numbers of strands are reminiscent of interlaced loving arms. During holidays, raisins and honey can be added, denoting the sweetness and joy of the festivities. Our loaf of choice during Hanukkah had raisins and honey, though we ate all kinds depending on what we could get.

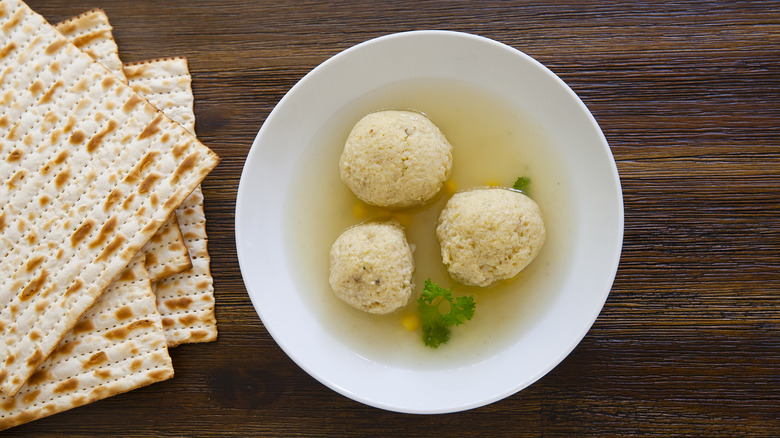

Matzo Ball Soup

While matzo ball soup is most commonly associated with Passover, it is a dish that appears on the Jewish dinner table throughout the year. The Ashkenazi Jewish equivalent for chicken noodle soup that is both comforting and delicious, this recipe features giant orbs of fluffy matzo meal combined with eggs, spices, schmaltz, and sometimes parsley. These luscious orbs are perched in a brothy chicken soup.

The significance of consuming matzo commemorates the Exodus of Jews from Egypt, a story traditionally recounted during the Passover Seder. While its inclusion during Hanukkah may not be customary, many Jewish families use this holiday to embrace all of their Jewish identity, including the story of the Exodus. It also makes for an ideal accompaniment to potato latkes and applesauce on a cold winter night.

Though you can make matzo balls from the leftover crumbs of a loaf of matzo bread, commercially manufactured matzo meal is sold in containers the way you would often find bread crumbs packaged. These are far easier to use for a quick matzo ball recipe. Some like to add baking powder or seltzer water to help lighten their matzo balls. Whatever you do, do not poach your matzo balls directly in your chicken soup, or they will soak up all of the beautifully seasoned broth. It is better to poach them separately in chicken stock, adding them to each bowl as you serve the soup.

Mandelbrot

Mandelbrot or mandel bread is the Ashkenazi Jewish answer to the Italian biscotti. While these twice-baked cookies became popularized in the 19th century, they likely originated in Germany and spread across Europe, where different variations became popular. The word mandelbrot translates to "almond bread," as many of the earliest varieties were made with almond meal.

The beauty of mandelbrot is its lengthy shelf-life. Because these cookies are baked twice, they are effectively dehydrated, making them crunchy and ideal for dipping into hot beverages like tea or coffee. Modern-day varieties are often made using baking powder and may or may not contain almonds. They are also frequently dotted with other ingredients, including dried fruit, nuts, and chocolate.

Though these desserts aren't necessarily a Hanukkah specialty, they are often served at Shabbat thanks to their ease of preparation and capacity for storage. They appeared during every holiday ritual and periodically throughout the year in our household, with raisins being the add-in of choice in the variety we baked. Ours also had copious quantities of vanilla sugar, making them perhaps a touch sweeter than the classic variety.

Roasted Chicken

Though one would like to find a definitive reason for the ubiquitousness of serving roast chicken for Shabbat dinner, none exists. What remains is how pervasive it is in the Ashkenazi household. Some surmise this has as much to do with frugality as anything else. Chickens are affordable and easy to prepare. In the old country, they would be invaluable members of a household. Unlike other meat, which has long been viewed as a commodity, chickens mature rapidly, making them ideal as the centerpiece of choice for a regular meal.

During the Hanukkah festivities, roast chicken is bound to appear at least once during the eight-day celebration. What is distinct is how each household opts to prepare it. Many have chosen to lean into Sephardic preparations, which often rely upon more exotic spices and cooking methods guaranteed to yield a moist, juicy bird. As for our household, we were old-fashioned, typically leaning into classic Eastern European variations. We used simple seasonings and counted upon the chicken's skin to baste the bird.

If you want to change things up, many Jewish homes are switching to fried chicken as a centerpiece to their Hanukkah and Shabbat meals. This makes sense for Hanukkah, considering the reverence with which oil is regarded.

Knish

The Brits have the pasty, the Spaniards the empanada, and the Ashkenazi Jew the knish. This dumpling-like delicacy originated in the 14th century when Jews fled Western Europe to Eastern Europe and beyond. The word knish translates to "little person" in Ukrainian, which befits its dainty size.

Though recipes are as diverse as households, traditional iterations became known as a vehicle for potatoes. The pastry and the filling took advantage of the starch, combining it with items like onions, mushrooms, and cabbage. A knish may remind many of a Polish pierogi. They are similar. Both can be boiled, baked, or fried and made in various sizes and shapes.

To incorporate them into a Hanukkah celebration, fried in oil fits the bill. Though savory is more common, sweet varieties containing apples, cheese, cherries, or chocolate have become popular. They are like the sophisticated variety of a Jewish hot pocket with flaky crusts and gooey insides.

Cookies

Though we don't often think twice about the annual Christmas tradition of making sugar cookies and decorating them, the tradition of doing something similar for Hanukkah may seem a bit more foreign. Some suggest that sweets, such as cookies, are produced to entice children to study the Torah. This may be a great way to bribe children, though it is more likely that the origins of cookies during Hanukkah came from German Jewish roots.

Making and eating cookies like Springerle, Spitzbuben, and Butterplätzchen is common around the holidays among Germans. Historically, these were stamped with clever wooden molds depicting animals and other images. Other recipes like Lebkuchen and Krokerle, made from various spices akin to a gingerbread cookie, were brought to America by German Jews immigrating to this country.

Today, cookies are often made using clever Hanukkah-themed cookie cutters that depict various symbols of the festival of lights. These cookies can be decorated and filled with jam or left as is. They are frequently decorated with blue and white icing, serving as a literal reminder of God and the teachings of Judaism. They are common gifts given, not unlike gelt, reminding Jews of the tradition of expressing gratitude to others during this holiday.

Chopped Liver

Chopped liver is another dish that may have a somewhat murky origin story. Its genesis likely comes from Medieval Alsace Lorraine, where geese were frequently raised for meat. Ever mindful of consuming every part of an animal, Jews who wanted to eat the liver for Shabbat would broil it to render any residual blood from the meat.

The resulting mineral-rich meat would be combined with onions and hard-boiled eggs before being slathered onto bread or crackers. Once Jews migrated to Eastern Europe, geese were replaced with chickens as a more frugal culinary option. The dish reached its apex when Jewish delicatessens popped up across major cities of the U.S., like New York and Chicago, where chopped liver became a popular menu item alongside myriad other specialties.

While it is less popular today due to concerns over its high saturated fat, chopped chicken liver is still a delicacy popular with many Jews out of nostalgia. The variation I grew up eating was made from schmalz, or the rendered fat from chicken skins, sautéed onions, chopped hard-boiled egg, and a hint of sour cream. Other iterations are garnished with what some call Jewish bacon, namely gribenes. These crispy chicken skin cracklings give the chicken liver an often welcome hint of crunchy texture.

Kasha Varnishkes

Kasha Varnishkes is a dish featuring buckwheat groats mixed with farfalle pasta and copious quantities of caramelized onions. Its roots squarely link to 16th-century Eastern Europe. At this time, buckwheat was the staple starch used for everything from porridge to bread to dumplings. Buckwheat was easy to grow and hardy. It is also a gluten-free grain.

In those early years, kasha varnishkes were made with homemade noodles that were more like pappardelle. It wasn't until Ashkenazi Jews immigrated to America that these homemade noodles were replaced with farfalle sometime in the early 20th century.

Today, it is often fashioned from a box of Wolff's kasha. The brand, founded in 1868, has become synonymous with this dish. Its appearance at Hanukkah signals to anyone in the know that something delicious is about to happen in the kitchen.

Many iterations of kasha varnishkes exist, including ones incorporating wild mushrooms. Others add gribenes for a crunchy texture and poached eggs for a luscious mix-in. This dish has become a pop culture sensation, appearing in an episode of Seinfeld and numerous cookbooks, including the 1999 "Star Trek Cookbook."

Blintzes

Blintzes are crepe-like pancakes of Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish origin, specifically from Ukraine and Russia. Unlike crepes, these pancakes were historically stuffed with a sweet filling made from cottage or farmer's cheese and never with a savory stuffing. The filling is often spread onto the pancake and rolled rather than folded.

Its appearance at Hanukkah celebrations has everything to do with the story of Judith and the beheading of the general Holofernes. The cheese-filled pancakes pay homage to this tale, reinforcing the symbolism and perpetuating its importance to Jews. For modern-day Jews, the farmer's cheese is often replaced with ricotta. This is sweetened with sugar and seasoned with vanilla, cinnamon, and raisins soaked in rum or brandy.

In my Hungarian Jewish household, we often served two types of blintzes, or palacsinta, as it is known in Hungary. One would be the classic cheese, the other a combination of apricot preserves and ground walnuts. Serving both on the same plate created a beautiful juxtaposition of flavors and textures. And if we were particularly cheeky, we would spread Nutella atop leftover palacsinta for a quick breakfast. It is Jewish comfort food at its finest.